THE FRIENDS OF MR. CAIRO

|

|

Talk to us on the Cairo Discussion Forums

See more summaries, synopses and scripts at the Cairo Radio Script Library

THE FRIENDS OF MR. CAIRO

|

|

Talk to us on the Cairo Discussion Forums

See more summaries, synopses and scripts at the Cairo Radio Script Library

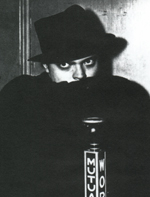

| Picture Vincent Price. A tall, well-built man with brown, widow-peaked hair framing a long, handsome face, large blue eyes, straight nose, wide, full-lipped mouth. That’s his physical appearance. On the radio, just his voice. Precisely enunciated, soft and mellow, smooth as velvet, or maple syrup poured over a waffle. And all about him, the radio programs. Born in the 1920s, booming in the 30s, golden in the 40s, busted by a monster called television in the late 50s. While it reigned supreme, the Theater of the Mind took listeners into a world made real by their own imaginations, a world of sound rather than sight, a world where the voices of actors and the ingenuity of sound effects artists gave everything plausible, sometimes terrifying life. A terrifying life that brought Vincent Price ever lasting radio fame one day. |

| The CBS anthology series Escape debuted on July 7, 1947, and for seven years featured a ‘hair-raising, audience-pleasing blend of epic adventure, running the gamut from historical adventure to westerns to science fiction to macabre horror, featuring stories adapted from the works of literary greats,’ according to radio historian John Dunning. These greats included Edgar Allen Poe, H. Rider Haggard, Daphne Du Maurier and Ray Bradbury. But they weren’t enough to satisfy the insatiable need for scripts. Books and magazines were mined for possible stories to adapt, including a magazine called Esquire. Esquire was founded in Chicago in 1933. Originally a trade magazine for men’s clothing, it immediately established its name as a showcase for literary writers, most notably, Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. French writer George Toudouze became part of this august company in 1937. Born in Paris in 1877, he earned a doctorate of letters at the Sorbonne, became a Professor of History and Dramatic Literature at the Paris Conservatory, and served as chief editor of The French Maritime and Colonial League. He wrote at least nineteen books about the sea, twelve plays, and nine books on art and architecture. But it is because Escape dramatized his short story about the fate of a trio of unfortunate lighthouse keepers, called Three Skeleton Key, that Toudouze’s name is known today. CBS staff writer James Poe adapted the short story for radio. The author of hundreds of original scripts for Escape and other programs, Poe’s writing style is unmistakable, with a piling on of adjective upon adjective, menace upon menace. He took Toudouze’s story and made it his own. In Toudouze’ version, the three men had no personality, no life. On the radio, Jean was the eager and enthusiastic novice, Auguste an egocentric ex-actor and hunchback, Louis stolid and taciturn and yearning for peaceful solitude. (Toudouze does, however, explain why the lighthouse and its rock are known as Three Skeleton Key, an explanation that does not appear in the radio program until the versions reprised for Suspense.

Three men work the light at a lonely lighthouse on a barren rock off the steaming jungle coast of French Guyana. One day a derelict ship, filled to the gunwhales with huge, starving rats, crashes on the dangerous rocks and sinks beneath the waves. Its crew of rats don’t drown, but head en masse towards the lighthouse and the many varieties of defenseless food within.

Although TSK was immensely popular with listeners, it was not an immaculate conception. (Vincent Price wasn’t among the cast!) Elliott Reid played the narrator, Jean, (pronounced John) with thin, reedy, uninvolving tones; Harry Bartell voiced the ex-Grand Guignol actor Auguste with little inflection, and William Conrad was a Louis (Lou-ee) who sounded more angry than afraid of the voracious army laying siege to the lighthouse. But thanks to hundreds of requests, TSK was reprised only four months later, on March 17, 1950. This time, it was golden. Grouped together around the microphones this time were Jeff Corey as Louis, Harry Bartell reprising his role as Auguste, and Vincent Price as Jean. Once more wielding the corn starch packages and other materials necessary to portray the chittering monsters (effects which had been awarded a ‘Best of the Year’ prize by Radio and Television Life Magazine the first time around) were Cliff Thorsness, Gus Bayes and Jack Sixsmith. By 1950, Missouri born-and-bred Vincent Price had conquered Broadway (his U. S. acting debut was in Victoria Regina opposite Helen Hayes, and his triumph had come in the long running Angel Street as the despicable Jack Mannenheim who tries to drive his wife insane.) He’d made over thirty movies, from science fiction ("The Invisible Man Returns") to historical drama ("Hudson’s Bay"), to film noir ("Laura"), and displayed his manic comedic talents unforgettably in "Champagne For Caesar". On radio he'd starred as ''The Saint'' from 1947 to 1951, and made dozens of other guest-star appearances. And it was on radio and not film that Vincent Price made his memorable horror debut.

As Jean, the new keeper who first spots the rat-infested ship sailing inexorably toward the rocks surrounding Three Skeleton Key, Vincent Price’s voice ran the gamut of emotions. From his opening lines, describing the lighthouse and his compatriots with jejeune enthusiasm, his voice takes on and maintains an edge of muted terror after the arrival of the rats. "The light drove them mad as she swung slowly and smoothly about. It blinded them in the fierce, stabbing bar of light, moving continually about, ever turning, ever touching, ever moving around and around. And they, twisting and stuttering, eyes flaming when they were struck by the light. The bright light moving and, behind, on the dark side of the room, so close -- so close I dared not turn my back but you cannot help turning your back when you’re in a room made of glass -- on the dark side of the room, you could not see them. Only their eyes. Thousands of points of blank red light, blinking and twinkling like the stars of hell." Harry Bartell’s acting is much more over the top this time around, as befits an actor of the famous Grand Guignol theater in Paris. "Yes, yes, indeed! Played in over two hundred different productions, dear boy. At the Grand Guignol. Oh, but it was monstrous, horrible, the way we used to scare the audiences. I-I was hated. Yes, yes. They used to throw things, and hiss, and bare their teeth at me. Finally, it got too bad. I couldn’t stand it any longer. I gave up the theatre. My nerves, you understand. Yes, gave it up completely, I really did. Couldn’t stand it any longer.’’ The fictional terrors that the Grand Guignol put its audiences through were as nothing compared to what lay in store for the three lighthouse keepers, especially for poor Jeff Corey’s Louis, who disintegrates from the proud, taciturn headman of the lights to a whimpering baby after one of the rats tears his hand open.

''Would you like to come in? Would you? All that I have to do is tap a little harder...'' Louis, driven insane with fear, contemplates ending his terror in rather horrible fashion. Tune in For Terror card set.

But there were more live broadcasts of TSKto come. If listeners couldn’t get enough of a show, producers knew enough to give it to them again and again. Not simply re-running the same broadcast, but actually re-creating it live. Many popular ‘one-offs’ received this treatment - the most famous example is the case of Suspense and the classic "Sorry, Wrong Number". It was so popular that every year for the next seven years after its debut, Agnes Moorhead (known today for her Margot Lane opposite Orson Welles’ radio Shadow, her Twilight Zone tv episode, and Endora on Bewitched) recreated the role of bed-ridden victim for a new generation of fans.

Agnes Moorehead in Sorry, Wrong Number

All good things must come to an end, and even masterpieces apparently have to be re-mastered in order to accommodate shorter running times and more commercials. For Price’s final go-around as Jean, in 1958, the opening was briefer, the supporting cast had fewer lines. There were more sound effects and there was more, and more dramatic, music – purists would consider this unnecessary as there was already drama enough! Yet Price’s new rendition was masterful as always. Eight years had passed since his debut. Instead of a fresh-faced young man, Price gave voice to a Jean who was a weary old salt who’d seen too much horror and gotten used to it. Audiences weren’t so weary, but they would never hear a live broadcast Three Skeleton Key again. Twenty years after Three Skeleton Key first aired, Leonard Maltin appeared on National Public Radio’s Fresh Air, to promote his book "The Great American Broacast". He brought along sound clips of various radio shows. One of these was the March 1950 Three Skeleton Key. Maltin described it, quite accurately, as "one of the most famous in all of radio."

Air Dates

Suspense |

The Complete Films of Vincent Price, Lucy Chase Williams, Citadel Press, 1995.

WEB RESOURCES

The original script for Three Skeleton Key can be read at:

http://www.oocities.org/emruf2/otr/key.html

The Elliot Reid 1949, original broadcast of TSK can be heard (via Real Audio) on Seeing Ear Classics’ website:

www.scifi.com/set/classics/skeleton/

The ‘golden’ version, the Vincent Price version of March 17, 1950, can be heard via Real Audio at:

antiqueradios.com/programs/shtml

Please note a version of this article first appeared in the October 1999 issue of the ezine Horror-Wood.

The Great American Broadcast, Leonard Maltin, Dutton Press, 1997.

Vincent Price – His Radio Appearances. Martin Grams, Jr. in Vincent Price, Midnight Marquee’s Actor Series,

edited by Gary J. and Susan Svehla, 1998.

Lighthouse Horrors, edited by Charles G. Waugh. Down East Books. 1993. (Contains the original short story by George Toudouze, and is where you'll find out why the episode is called ''Three Skeleton Key.''

CBS’s 60 Greatest Old Time Radio Shows, An Anecdotal Guide to CBS’s 60 Greatest Old Time radio Shows, by Anthony Tollin and William Nadel. Radio Spirits, Inc. 1998.

Support THE FRIEND OF MR. CAIRO by purchasing Vincent Price videos from Amazon.com (click on a cover):

|

''Lamont. Listeners of The Shadow can support The Friends of Mr. Cairo

tremendously by buying this Panasonic Carousel DVD Player from Amazon.com. Click on the picture.

|

This page sponsored by these books:

|

Return HOME |

| A BAP's Legacy website |

|