| . |

| . |

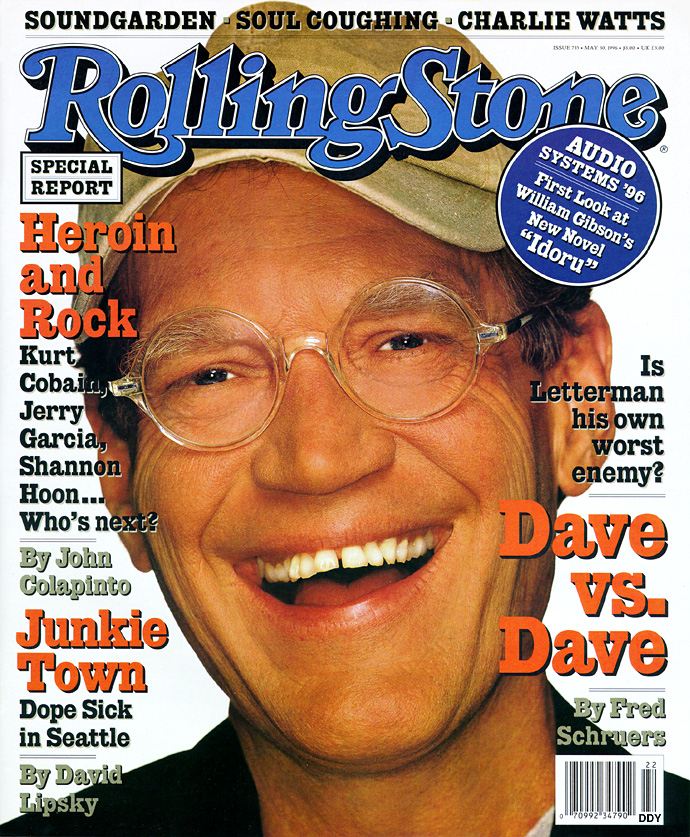

| Rolling Stone - David Letterman Interview "It was just a crossroads." We're used to seeing David Letterman's eyes antic, unbespectacled and camera-ready. To sit in a small, windowless and nearly soundproof room with him, looking across a bare wood table under unsparing fluorescent light, is to risk getting spooked. Fatigue and the complete absence of Letterman's manic onstage zeal make him seem emotionally near-naked. His dentist-style spectacles magnify his eyes' size and intensity. He's wearing a T-shirt, sneakers and khakis rather than the double-breasted suit and gleaming shoes we see on television, and the mood might be more casual if those eyes (except for scattered moments of grudging amusement at his own offhand riffs) didn't look so very grave and tired. "I'm so exhausted," says Letterman. "I'm too old for this." For the first time since Letterman began bringing audiences such phenomena as haunted pancakes 14 years ago, it's possible to believe that. The crossroads he's speaking of is both personal and professional; for Letterman, the two are hard to separate. Not the least of his problems is a serious slide in the ratings. He burst out of the gate with the Late Show's debut on CBS, on August 30, 1993, beat Jay Leno's Tonight show solidly for almost two years and then, in the aftermath of his much dissected debacle as the host of the Oscars, began to lose in the ratings race not only to Leno but often, on big news nights, to Ted Koppel's Nightline. This sweeps month of May finds Letterman hoping for a ratings surge after the Late Show road trip to San Francisco. He's punching away at the lead Leno holds. "Make no mistake about it," Letterman says, "we would rather the rating situation was the way it was six months ago. It's not that way, and it may be a long time before it is again...It's like, OK, we got new cards. Let's take a look at the hand we got and go. Now the pressure is on me to perform up to the level of what is being given to me." It's a pressure Letterman is responding to with ferocious energy, working long rows of 14-hour days and running around city and suburb to shoot the taped "remotes" that take advantage of his quicksilver comic-improv skills. We'll be seeing more of the Letterman who slurps engine oil (actually chocolate syrup) off a dipstick to try to get a rise out of a mechanic. But the problem, to many close observers, is that the pressure has created a kind of Creepy Dave who's increasingly frenetic, splenetic, self-flagellating and squirelly on the telecast. If Letterman were an action movie, now would come the shots of the bolts in the engine mounts breaking loose, the switch at the junction getting thrown the wrong way. But in the movies, hostile forces monkey with the hero's fate; Letterman seems to be driving this current rattletrap himself. If he's still got his cigar clenched in his teeth at a jaunty angle, and if the Taser-quick wit still makes him a man "who eats punks like you for breakfast" (per a recent show intro), many of those who know him best have lately begun to worry about his steering. But who's going to tell him? The exit door at Letterman's production company, Worldwide Pants, has been swinging fast. He recently fired his longtime sidekick and executive producer, Robert Morton, so abruptly that Howard Stern swore he heard "Morty bouncing on the awning on his way to the sidewalk." A significant percentage of writers have left for other shows, along with segment producers Daniel Kellison and Mary Connelly. Longtime director Hal Gurnee left in June to free-lance, and former resident sage Peter Lassally now produces Tom Snyder's show in L.A. (Meanwhile, CBS president Howard Stringer, instrumental in bringing Dave to the network, moved on, and Dave's agent, Mike Ovitz, took an executive post at Disney when it merged with ABC.) "I think it's very dangerous to shake up a staff," says a show veteran, "because it's always felt on the air." Indeed, to go by the Internet postings that serve as electronic worry beads for the show's producers, the changes are both visible and audible to the fans. "It was Dave's little clubhouse," says the veteran, "and these were the members of the club: Robert Morton; Paul Shaffer, Bill Wendell, the announcer; Hal Gurnee, the voice in the control room. And one by one, Hal is gone, Bill Wendell is gone, Robert Morton is gone. Dave's clubhouse is just really Dave now and Paul. And it's a little different." The defenestration of Morton took place on the evening of March 8, not long after the week's last show had wrapped. Both Letterman and Morton had vacations scheduled -- Letterman to his usual retreat on the Caribbean island of St. Barts, Morton to his rented villa in Tuscany. Those close to Morton paint the event as a cold surprise coup; from Letterman's side, it was the only possible response to a power grab by the gone-Hollywood Morty. "This was not," says Letterman, "'Let's go downtown and lynch him, get the rope.' As with everything else, there is a back story and some drama and some intrigue. "Bob had told me on many occasions," says Letterman, "that he was getting to a point where he no longer wanted to produce the show on a nightly basis. In addition, he wanted to bring a friend in, who I know of but had never worked with, to take over that job. I found that unacceptable. We've got to step up our game. I don't want to do that with a stranger. Bob had been very useful to us, just great for us, but we had so many things going on, so many people leaving, so much difficulty with the writing staff -- every aspect of the show absolutely needed attention." The firing came after several weeks of discussions between the suits; Morton's manager-lawyer team and Letterman's reps had been trying to hammer out Morton's new arrangement. It was clear that the best Letterman could offer him was co-executive-producer status with Rob Burnett, a former head writer and ascendant Letterman confidant. That was a take-it-or-leave-it offer Morton was almost sure to refuse. "It was tough," says Letterman. "I knew for about three weeks I had to do it, and I would wake up every morning thinking, 'I can't do this, I can't do this, it's just horrible.' But then I just recognized that as an adult, there are responsibilities greater than individual feelings in life sometimes. And so I did it." Years before, trying to retool his old NBC morning show, Letterman and his then manager, Jack Rollins, had to fire their producer and a handful of staffers. "I'd never done anything like this before," says Letterman. "My previous regular job had been, you know, running a cash register in a supermarket. Jack and I fired these people one at a time, and because we had never done it before, we took our time, and we ended up counseling these people, and it went on and on. And at the end of the day -- literally it took from 2 in the afternoon to 8 at night -- we were just limp, we were exhausted, it was a horrifying situation. So I have since refined that process: When you have to do this, let them sit down, tell them what exactly is transpiring, and then get up and extend our hand and thank them. And then if you want, you can talk about it later. But a swift, clean cut is the best way for everyone." Letterman insists that the faintly bizarre sketch Morty took part in some 25 hours before his firing was sheer coincidence. As Morton stood beside an old lady whom -- the sketch would have it -- he was promoting as a human-interest story, Dave pointed out she was clutching not a swaddled baby but a salami. Then, as the boss taunted him, Morton exploded in a fake ire, barking, "Climb off my ass, freako!" It was to be his on-air swan song. Those close to Morton say that on the fateful Friday evening, he figured he was being summoned to Letterman's office on ordinary business. The two men met alone for 15 minutes, and apparently, though Morton chose not to shake Letterman's hand, there was neither an angry outburst nor a warm farewell -- just a rather numbed and unceremonious leave-taking. Letterman and Morton had apparently agreed to keep the controversy out of the papers as much as possible, but sources say that tack was doomed when Morton was handed a planned press release announcing that Rob Burnett would take over and Morton was to be kicked upstairs. Morton asked for a day to revise it and, in the hours he had before flying off to Italy, worked the phone with his host of contacts in the media. At first, he even made nice: "I don't think anybody's acting malicious here," Morton was quoted as saying in a wire report. "I'm personally very pleased with this shift." Even as he sat on the JFK runway before his flight to Italy (alongside current steady Jamie McDermott, herself a TV executive mulling over a move from NBC to ABC), Morton was on the phone with a Los Angeles TV reporter, praising Letterman as "the most talented man in television." The New York Times' Bill Carter reported on the following Wednesday that one staffer called the dispute "a him-or-me thing" and that "Mr. Morton had resisted sharing his duties with a man whom he had once hired as an intern." Newsday's Verne Gay wrote of the "cold, cold" world of late-night TV: "One day you're the toast of Broadway and the Hamptons...the next day, you're just toast." Although Morton knew how to handle "the world's most talented and miserable late-night host," Gay added, the two had grown apart: "To put it bluntly, Morty had gone Hollywood. Letterman, who despises what he sees as that town's frivolity and shallowness, had enough." According to one insider, the firing is bound to affect viewers' feelings toward the show: "In their minds, there was always that family that was out there, whether you saw Morty or not. To remove a producer in that manner, that's one thing. But you don't remove a cast member, you don't take away somebody from an on-air job that way. They could have very easily said, 'Our friend Morty is leaving,' and showed a little videotape and shaken hands on the air. I'm sure Morty, with a financial interest in the program and having taken a hand in creating it, would have stepped back very graciously." Letterman, usually the king of autocriticism, doesn't see it that way. "I don't want this to appear that 'that goddamn Morty, he had it coming.' It was circumstantial, and it was not punitive and it was not vindictive. It just needed to be done. The only regret I have of this is I fear that Morty now will, you know, be an enemy of mine for the rest of my life." Nonetheless, Letterman says, "I kind of resented the notion that 'Oh, Rob Burnett pushed his way in, stabbed Morty in the back.' It just didn't happen that way. Morty pretty much by his own hand designed this. It was no chicanery, it was no skullduggery, it was no clandestine, scheming plot. It was just -- we had a little infection, and the limb had to come off." The Late Show field hospital has been open for business since about halfway through the March 1995 Academy Awards telecast, when Letterman's kingly stature began to suffer some wounds. He'd turned down the host job once before, but the challenge of it all, the allure of trying on shoes that had been worn by his idol Johnny Carson (who'd hosted five times) and the sheer exposure the gig would bring overcame any second thoughts. In what now looks like a mistake, he and his staff tried to take the Late Show's rude, chaotic energy and set off a bottle rocket from inside the static vessel of the Oscars. In fact, Dave spat out quite a few sparks, zinging both action figures (Eat Drink Man Woman was "How Arnold Schwarzenegger asked Maria Shriver out on their first date") and the politically correct Tim Robbins and Susan Sarandon ("Pay attention: I'm sure they're pissed off about something"). But the show, which has been called "entertainment-proof" was clearly Dave-proof as well. By the time he and his entourage had flown home, they had the morning papers' pans to read. The New York Times' headline two days later was typical enough: THE WINNER ISN'T DAVID LETTERMAN. The bit that bore a disproportionate share of blame came early, when Dave said, "I've been dying to do something all day ...Oprah, Uma. Uma, Oprah." "'Uma, Oprah' is completely 100 percent my fault," says Rob Burnett, who at age 33 looks almost too pixie-ish to be cast as the villain in the Morton camp's scenarios. "I'm the guy. I should be out of show business. It still keeps me up at night." As for the negative reviews, he says, "Dave was a victim of expectations. People just wanted this to be the greatest Oscars in the history of Oscars, and the minute it wasn't that .." For his part, Letterman takes no consolation in the fact that he brought the awards show its highest ratings since 1983. "I wish that meant something," he says. The bigger issue for now is how thoroughly his image was damaged by the event. Morton has said that, post-Oscars, it became OK for the first time to criticize Letterman -- and an informed source feels the show's present blue period dates to then: "I still, to this day, believe that that's when things turned around. All of a sudden he was no longer the guy who couldn't do wrong." Four months later, Jay Leno -- helped by Hugh Grant's sheepish post-bust appearance on July 10 -- would creep ahead in the Nielsens, a lead he's basically held ever since. Joel Segal, director of national broadcasting at the ad agency McCann-Erickson, sums up where Letterman now sits with the core 18-to-49 audience: "For the most recent season, Letterman's ratings are down about 29 percent from what he had the prior year." Letterman, however, remains the clear winner among those aged 18 to 34 -- including the affluent males Madison Avenue craves most. "Under the circumstances," says Letterman, "we ain't doing that bad. Despite the erosion of households, we still win in the important demographics and are probably making as much if not more money for the network. That's nice to hear, because if you just look at the raw data, it looks like, 'Oh, my God, we've hit an iceberg, and it's a matter of minutes before we're in the lifeboats.'" "The key point everybody keeps forgetting," says CBS Entertainment president Leslie Moonves, "is we're doing well in that day part (i.e., late night) where three years ago we weren't. The Late Show is still CBS' biggest profit center and is even more important given CBS' own prime-time ratings nose dive. Moonves assures Dave that the lead-in cavalry is coming (though the signing of Bill Cosby and Ted Danson to do CBS shows skews to an older audience that eschews Letterman). Still, where did those people who deserted Letterman go? "They went to places other than Leno," says Segal, "because Leno is really only up about 4 percent. They probably went to cable." For Letterman, a Beavis and Butthead aficionado, the irony of seeing his audience depleted by them must hurt. On a Friday evening in early April, as the Late Show is about to segue from what's called Act 1 (comprising the monologue and a comedy bit) to Act 2 (the Top 10 list, followed by the first guest), some marvelous grotesquerie is about to erupt on the set. In a taped segment, hypnotist Marshall Sylver puts various staffers under. Biff Henderson, the cherubically pudgy and balding stage manager often exploited in Late Show skits, is induced to perform an alarming Madonna impersonation, complete with bleeped-out profanities, then is coached in the absurdity of Dave's big paycheck. Asked if Dave is worth the money, Biff snorts and tee-hees helplessly. This has all been seen on videotape, but now onstage, Letterman, reminded that Biff can be put under with one command, can't resist dimming Biff's lights just before reading the Top 10 list. "Sleeeeep," says Dave, and Biff lists sideways, jarring the camera. When Dave repeats it, Biff steps up ("like a punch-drunk boxer," Burnett will note) and slumps into the first guest's chair in a trancelike sleep. Either that, we can see the suddenly-not-chuckling Letterman thinking, or he's dead. As Letterman says later, "I thought, 'Oh, well, you're screwing around, his liver has exploded, and you're looking at a dead man here.'" Upstairs in the seventh-floor offices, a staffer vaults into the room saying, "Biff's really out! And Dave's really scared!" In the editing room, images from several cameras bounce around amid near-panicky chatter: "Add a minute twenty to the break!...Are we gonna can the top 10?...Get Sylver on the phone in Vegas!" Letterman, staring out toward Burnett at the producer's podium, looks thoroughly rattled as he takes Biff's pulse. "People will look at it," Letterman says now, "and say, 'Was he kidding? Was he pretending to be out? But I'm telling you, during the commercial that we extended, it must have been like five minutes, he didn't move nothin'. Didn't blink, didn't breathe hard -- nothing," Letterman's all-pro sang-froid coming out of the break is as startling as what went before. He tells the audience, "Biff, like many of our staff members, enjoys a nice nap during the show," then takes Sylver's call. When the thoroughly showbizzy Sylver tells Dave he's lucky to catch him between shows in Vegas, Dave needles him ("We have a medical emergency, but I'm glad things are going well for you there in Vegas") and wakes Biff up per instructions. At his best, Letterman celebrates chaos. Would he rather have a row of solid, topical, witty guests, or does he prefer the giddy feeling you get near the edge of the cliff, when Madonna starts spewing profanities, a dog craps on the stage or Biff suddenly sleeps? "You always would rather have something haywire," says Letterman. "You can only do the perfect show, you know, 80 times, and then you realize, 'Yeah, it's perfect, but something unpleasant and ugly and sloppy is more memorable.' I think that our track record is about 50-50, where we can get something out of it. So you do run a risk there. But it's hard to orchestrate anarchy every night." "That hypnosis show was different, it was totally out there," says Bill Carter, who wrote the Letterman-Leno history The Late Shift while on his Times TV beat, then co-wrote the HBO movie (which Letterman richly despised). "Maybe they need to do stuff like that. That's what got them a reputation years ago." This February's prime-time Late Show with David Letterman Video Special II evoked that comic strain. It included a favorite gag of making Rupert Jee, co-owner of the Hello Deli, toss out aggravating questions -- ad-libbed by Letterman and radioed to Rupert via an earpiece -- to ordinary civilians. Another successful gambit was having the host verbally pester young kids, drawing such retorts as, "You're annoying." "We were all pretty pleased with it," says Letterman. "I realized then that we are still capable of doing that kind of show each and every night. But we had to make some changes to accomplish that. And I felt Rob, who was the executive producer of the prime-time special, was the best person to give the reins of the show to." The special, Burnett says, made the Worldwide Pantsers ask, "'Well, gee, is the nightly show as good as this?" Seeing that kind of rejuvenated all of us -- 'We can still do this.' For me it was all in seeing Dave in his element, seeing him with Rupert, seeing him talk to kids. You realize no matter what anyone says, we're riding the fastest pony here. The guy is just amazing." Though Burnett may sound like a cheerleader, his rise is not due to flattery. Morton was a steadfast Dave-praiser in his own right, and vanity is not one of Letterman's vices. (When Charlie Rose remarked that people often praise him after a good show, Letterman shot back, "Well, they're little suck-up weasels.") But Burnett does have the dual gifts of making quick decisions and putting his boss, who can be shy even around his own employees, at relative ease. Burnett sifts and funnels a daily cascade of comic material to Letterman. One insider finds that Burnett's "extremely efficient, and he makes decisions very quickly." A lucky thing, because among other jobs he's the link between a dozen or so writers and the boss. The writers work long hours in relative seclusion, getting mostly passed-along feedback from Letterman. The staff winces when Burnett has to convince the host that a joke or scripted segment really can work -- just as Letterman's capable of turbo-charging a bit, he's capable of throwing one away on the air. "You can tell the nights Dave's pissed off," says the insider, "when he's doing things like saying, 'Hold CD up now,' when it comes up on the cue cards." (Perhaps there's some real-life resonance to one taped bit, unaired at press time, in which Dave induces two staffers to repeat after him, "The big guy wants clams.") If expert schmoozer Morton had been a thorough contrast to his brooding boss, Burnett is mostly rounded corners, at once private and affable, a guy who says, "I want to work at Worldwide Pants the rest of my life." Burnett, who grew up in North Caldwell, N.J., had been admitted to law school after college but "made the age-old bargain with my parents -- give me a year to try to do something else." He took his old Chevy to California, had no luck there, briefly worked for a New Jersey newspaper and, in August of 1985, was hired by Morton as an intern. Burnett free-lanced a few jokes at $25 apiece to comedian Wil Shriner and then began contributing lines to Letterman's monologues, becoming a full-time writer in 1988 and head writer in 1992. He made his bones supervising remotes, scripting situations that could serve as a launching pad for Letterman's interactions with people in the street. Last summer, Letterman asked Burnett to move to L.A. (uprooting his wife and infant daughter) to supervise Bonnie, the sitcom Letterman was executive-producing for his pal Bonnie Hunt. She and Burnett wound up clashing, "I think it was one of those things where we probably should have dated first before we got married," says Burnett. "If I speak German and she speaks French, how can you collaborate?" "It just wasn't working," says Letterman. "Bonnie is a very strong, smart, talented woman. And so is Rob, oddly enough. But it wasn't compatible." Burnett moved back east and began developing his own Worldwide Pants-CBS sitcom, Ed. During the long, hard months that Letterman's ratings sagged, the host began looking for fixes, finally offering Burnett executive-producer status alongside Morton, a symbolic share in the company and presumably a big raise (though probably nothing matching Morton's reported $2-million-a-year salary). Amid murmurs about Burnett's supposed ambitiousness, amid a passel of conspiracy theories, including the thesis that Letterman's CAA agent, Lee Gabler, was looking to increase his client's dependence on him, the bottom line may be that Letterman simply was trying to get back to what worked for him over the years -- and wanted 100 percent commitment from whoever was asked to take him there. "Rob's raring to go," says Letterman. "He deserves this under any circumstances. I'd go anywhere for Rob. He's the guy you want to be stuck in an elevator with. He'll not only figure out a way to escape, but he'll do it in an entertaining fashion. We've been in some tight spots in our lives together, and I just think the world of him." "It's been said before that comedy is no joking matter," says Hal Gurnee. "It's serious stuff, and the people who do it best seem to be unhappy people. I think Dave always was clever, witty -- the smartass in the back of the classroom. That separates you, but it also gives you a place, it gives you status, gives you something that other kids can point to. And he's carried it on into his adult life and into a fantastic career." Now that Letterman's playing catch-up, that smart kid in the back of the class can turn, to use Dave's word, "berserko." Some recent monologues have been marked by mugging, false hilarity and a sense that, as someone close to the action puts it, "there's something unpleasant there." It's true that lately some of Letterman's less heartfelt heh-heh-heh-heh snickers can sound as flat and mean as someone emptying a .22 into a rabbit. One source thinks Letterman is probably castigating himself for the ratings dip: "It's such a cliché, but I think it's coming from insecurity. And self-loathing -- which is an ugly, maybe too strong a word, but it all has to do with not believing in yourself and not going with your strength. His strength is not in being frenetic; his strength is to sit back, observe and then say very smart, funny things. He's a very smart observer, and he's losing that. Now both the Jay Leno show and the Letterman show are frantic, and both are filled with scripted comedy. Dave's strength was the thing that Jay Leno can't do -- be truly funny on the spot." Robert Morton used to incessantly point out that much of Leno's updated format was lifted from Letterman's. On any given night each host can be seen scampering out of the studio on some prepared gag. (Letterman's bits, thanks to his improvisational élan and deftness at physical comedy, usually score better than Leno's) Letterman has complained that in the hellzapoppin' days when he debuted at CBS with bits like Debra Winger's stripping down to a Wonder Woman outfit, he created a monster he called Dave's Big Top -- a mood he saw as, "Let's see what Party Boy is doing tonight!" With Burnett in place, the trend will be toward darker comic fare like "Weird Guy in Elevator" ("I like cheese"), as opposed to the sheerly zany. "For me," says Burnett, "the goal of all the comedy we do is just, 'Let's put Dave in situations where he can be himself.'" Given the difficulties of attracting the film and TV stars to whom the L.A.-based Leno has ready access, Letterman has muddled through with some guests who clearly don't interest him. ("Sometimes he would just stop listening," says Gurnee, "and it would amuse me and I would get pissed off at the same time.") Though Letterman clearly enjoyed gripping Elle Macpherson around the torso when she turned up recently, he introduced her somewhat sardonically as "truly one of the world's most beloved leggy supermodels." (Instead of showing the clip from Jane Eyre she'd brought along, Letterman grinningly aired an embarrassing snippet from her workout video.) Glamorous guests bring out the host's enjoyable geekiness, as he shares confidences like "A squirrel tried to mate with my hairpiece" and "Je suis le grand garcon." "Dave doesn't like show business," says Gurnee, who's often sat in Dave's Batcave and watched college baseball or bass-fishing shows. "He doesn't like people in show business, because he's from Indiana. The first time I met him, he was supposed to interview me about doing the show, and we spent about 15 minutes talking about how his father used to make sauerkraut and pickles in their basement. Then he said, 'Gee, I'd really like to have you do the show.' He knew that he could talk to me. I think some old lady who comes on has a lot more to say to him than a stand-up comic who is out there just selling himself with that whole phony show-business mantle." Normally charmed by and solicitous of kids, Letterman clearly took a dislike to the uncommunicative 13-year-old actress Anna Paquin on a recent visit, staring over her shoulder with his lips set in a cartoonish "this sucks" expression. The show had opened with a guy trying to sink a basket from the three-point line for $10,000. He anticlimactically missed, so Letterman later gave Paquin a shot from closer in. When she heaved in an off-the-glass line drive, the host gleefully handed her the 10 grand. The producers took it away backstage, resulting in what Burnett calls Paquingate. Her parents beefed to the local tabloids, and Paquin came back two nights later so Dave (with thinly veiled disgust) could hand the dough back for a donation to the Make-a-Wish Foundation. A few minutes later, addressing himself to anyone who'd been bothered by the incident, he spat out, "Get over it, all right?" As he says now, "I just thought 'This is the epitome of hypocrisy.' Here's this little girl, just dumb luck, hits the shot; I as a joke hand her the money -- it's show business. It wasn't like 'gimme that 10 grand, you little... It would be different if we were dealing with a Bosnian orphan. We're dealing with an Academy Award-winning movie star, who's in big-budget movies." Nonetheless, says one source, "the recovery from it was as bad as the original mistake," Also in the tabloids that week was a report that the recently dismissed Morton had been overheard in a juice bar growling, "There wouldn't be any Worldwide bleeping Pants without me," which is perhaps why Dave grabbed the paper with the Paquin story and muttered, "Is there anything else in the paper I need to apologize for?" (What the tabloids didn't notice was Morton, three Fridays after his firing, dining with Jay Leno and Leno's wife, Mavis, at the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas.) "Dave is an absolute perfectionist," says CBS' Moonves. "I've never seen anybody who cared about detail as much as he does. He has one of the best work ethics of anybody I've ever been in business with. Maybe it's not the best thing for his personal health, but that's the way he's built, and I think that's why he's so successful." Although as he approaches 49, Letterman complained that he "can't stay up late enough to watch my own show," he's notorious for prolonging his days at the office to agonize over the shows he thinks flopped. Letterman's woes are not solely of the spirit. For some 10 years he's been fighting chronic pain in his neck, the result of a whiplash injury in a car accident. "I'm not pulling rivets or tossing ingots, you know?" he says. "It's mostly indoors, and there's no heavy lifting, But unfortunately the neck is an area physiologically where stress is stored, and if the machinery is overloaded with stress, next thing you know, you're seein' birds. It won't kill me, but it'll drive you nuts, you know? It makes you feel like an old man. 'Oh, jeez, I can't move.'" In fact, life at $14 million a year can be pretty good. Letterman likes to say he spends weekends "hiding under the house," but on breaks he's more likely to travel with girlfriend Regina Lasko to St. Barts (where, one observer says, "lunch costs $3,000" and Letterman won't be pestered by ordinary citizens). Letterman, who says of Lasko, "She's my current girlfriend and has been for the last eight years or so," admits that she "really, really, really would like to get married. It makes perfect sense, but I still have not brought myself to that commitment just yet. It's not because I don't care about her, it's not that I have any deficiency or she has any deficiency, it's just...I feel like, well, I did that once and...it was my fault it didn't work out...I guess I'm being immature -- emotionally I'm very immature. On the other hand, if I am ever going to be able to have children, most women probably would want to be married before you pursued that. And that's something that I have to address pretty quickly because I'm going to be 49 in a couple of days." During the third week of April, Letterman and Co. emigrated to San Francisco to shoot remotes and gather steam for the week that would usher in May sweeps. Meanwhile, they aired reruns, including an exemplary show from last May's trip to London. We saw a free-and-easy Dave, a guy who actually looked comfortable in his stardom. Though the local press largely scoffed at his topical British jokes ("Let's just make him Lord Acerbic of Ironyville!" sniffed the Guardian), he was actually great fun playing America's Joe Lunchbox for the Brits, confiding that Princess Diana "spent the night at my place once," delivering a pork chop to a hard-drinking working-class gent he befriended, accepting the Top 10 list from Salman Rushdie. Guest Meg Ryan giggled contentedly as Letterman said, "I believe in my heart that you're a goddess." His mother came on, getting an air kiss, flowers, then an actual peck from the son who may secretly be as shy as she is. (The cult of Mom seems quite strange given the remoteness that comes across when they're together on camera.) The London show's best moments were wonderfully nonsensical in classic Letterman style. He found a nicely dressed local, equipped him with a cell phone and badgered him with calls and chores. "Can you eat a scone in 15 seconds?" Dave said, then, standing just feet away, interrogated him via phone all the while, creating crumbs and laughs in profusion. It was gloriously moronic, a had-to-be-there moment, which, thanks to video, we were. No matter how sharply Letterman's numbers dip, no matter how worrisome his self-flagellating becomes to those who nurture a fondness for the possessed fellow, we still recognize the particularly Lettermanesque laugh that at once embarrasses and refreshes us. And no matter how much he squirms and gyrates in the harsh light the ratings cast on his damaged dominion, Letterman, and those laughs, are not going away. |

| C |

| "Is Letterman his own worst enemy?" "Dave Vs. Dave" "Forget Leno & Koppel -- Letterman may be his own worst enemy" By FRED SCHRUERS |

| Late Show With David Letterman Webpage> |

| Rolling Stone Interview |

| Home | Bio | Pictures | Baby Page | Episode Transcripts | TV Interview Transcripts | Interviews & Articles | Quotes | Wallpapers | Links |

| May 30th 1996 |

| T Bone's Late Show with David Letterman Webpage Contact Me |