Enver Pasha and His Times

Back to the Solving

Problems Through Force Homepage

Back to the Solving

Problems Through Force Homepage

|

Prologue:

In the land of the oriental despot |

|

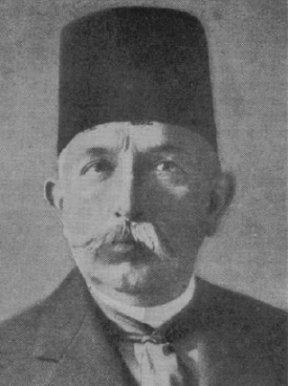

"The Red Sultan" Abd-ul Hamid II. So nicknamed by his contemporary journalists in

the west for the brutal massacres of Armenians that he nodded to in the

Eastern Vilayets in 1894 and again throughout the city of Constantinople

in 1896. He was regarded as one of the most clever and able rulers of his

day. He also witnessed the greatest decline of the Ottoman Empire in its

history. Misfortune began as he came to power in 1876 amidst the turmoil

of the Bosnian insurrection, war against the feudatory Serbia and

Montenegro, and the Bulgarian massacres. The Young Ottomans forced him to

grant a western style constitution complete with a parliament, but he was

able to consolidate his power and suspend it when the Russians marched

against him. After a dramatic and brutal siege at Plevna through the fall

of 1877, the Russians finally broke through and stood at the shores of the

Bosporus. "The Red Sultan" Abd-ul Hamid II. So nicknamed by his contemporary journalists in

the west for the brutal massacres of Armenians that he nodded to in the

Eastern Vilayets in 1894 and again throughout the city of Constantinople

in 1896. He was regarded as one of the most clever and able rulers of his

day. He also witnessed the greatest decline of the Ottoman Empire in its

history. Misfortune began as he came to power in 1876 amidst the turmoil

of the Bosnian insurrection, war against the feudatory Serbia and

Montenegro, and the Bulgarian massacres. The Young Ottomans forced him to

grant a western style constitution complete with a parliament, but he was

able to consolidate his power and suspend it when the Russians marched

against him. After a dramatic and brutal siege at Plevna through the fall

of 1877, the Russians finally broke through and stood at the shores of the

Bosporus.The victorious Russians imposed on the Sultan the Treaty of San Stefano, which was to cost the Turks most of their European territories. The Great Powers intervened, not for the Sultan's sake, but to deny Russia its advanced position in the Balkans. Thus, the Sultan's power in Europe was maintained but his authority would be contested several times: in 1885, when his feudatory Bulgaria annexed the Turkish province of Eastern Rumelia; in 1894 and 1896, amidst the Armenian massacres, when the Great Powers referred to the Treaty of Berlin [replaced the Treaty of San Stefano] and its clauses concerning reforms in the Eastern Vilayets; in 1897, when Greece used rebellions on the isle of Crete as an excuse for war, but was severely defeated; in 1902, when komitadjis in Macedonia rampaged through the Balkans and brought fierce Turkish reprisals; and in 1903, when the Muerzteg programme was implemented in order to bring reforms to those provinces. Such programs of reform were considered by the Turks to be foreign intervention, and anti-Mohammedan in nature. Islam as a unifying force was something that Abd-ul Hamid II drew up as no other Sultan before him had. Although the Ottoman Sultans had claims to the Caliphate as far back as the XIV. century, they did not assume the mantle until the XVIII. century, and under duress. The idea of Sultan-Caliph was reinforced by Mahmud II when he was fighting his rebellious protege Mohammed Ali of Egypt in the late 1830s. Forty years later, Abd-ul Hamid II saw the aura of theocratic mastery as a truly nonwestern method of reining in the progressive western tendencies of his opponents. In this, Abd-ul Hamid II granted ground-breaking support to the wild Kurdish tribes in the Eastern vilayets, and these people turned against their Armenian neighbors, who were wealthier. Abd-ul Hamid II also increased contacts with pan-Islamic forces outside of the Ottoman Empire, in order to rebuild prestige lost from the Russo-Turkish War in 1877. This idea of pan-Islam was taken to heart by most Moslems throughout the world--Islam by nature is a single authority, both spiritual and civil. However, the people who would have the greatest impact on the destiny of the Ottoman Empire as it entered the new century were those who tried to reconcile western-style reforms with pan-Islamic ideals. Such as the Young Turks... Added to the mix was an undefined "Turan movement." Essentially, it started when the Young Ottomans had tried and failed to win their parliament. The new consciousness among Turks that they were not merely Moslems and soldiers was fertile ground for aggrandizement. Thus was born the idea of Turan, a homeland for the Turks, stretching from Anatolia all the way to the Gobi desert. Abd-ul Hamid II was generally opposed to the pan-Turanian movement, because it conflicted with the Islam-only effort underway. He was opposed to the creation of a Turkish nation-state in the heart of his empire. GWS, 10/00 [rev. 2/03] Top |

||

|

Part 1:

And a savior was born |

|

Ismail Enver was born in Abana, near Constantinople, on 23 November 1881 to a working class family from Monastir (today Bitolj, Macedonia). His father Ahmed was a Turk, who rose from being a porter to a railway official and acquired the honorable Bey. Enver's mother, Aisha, was an Albanian from the Monastir region, who had the distasteful job of laying out the dead, thus making her an outcast among her own people. Although most histories suggest a humble origin for Enver and his family, it would appear that Ahmet was not entirely penniless, and may have found his wife while on duty in the army. The family had a long military tradition, and Enver's uncle Halil was an officer in the First Corps. Enver joined the military academy and then entered the Turkish Army as a subaltern, followed by his brothers within a few years. Enver served for several years in the III. Army Corps, which brought him to his mother's homeland in the wilds of Macedonia, where he took part in the anti-bandit campaign in 1903. He was then stationed in the relative calm of Salonika, where he came into contact with elements of the Young Turk movement. This nascent political party spread as much disaffection among the demoralized officers and troops in the city as the komitadji rebels spread chaos in the countryside. The Ittihat ve Terakki (Committee for Union and Progress) had as its primary aim to force the Sultan of the Empire to return to Constitutional Monarchy first attempted in 1876. At the turn of the new century, Turkey was wracked with

disaffection among the army and navy personnel for widespread corruption

and abuse. There were many rebellions and mutinies in the army especially from 1905

until the time of the revolution in 1908. The navy was in

particularly bad shape. Sultan Abd-ul Hamid II, whose palace of Yildiz was

on the shores of the Bosporus, feared a naval mutiny that might result in

a warship steaming into the Bosporus and shelling his palace. Therefore,

he had every Turkish ship disabled and confined to the Golden Horn. The

shameful disrepair of the navy was but one aggrievance by the Young Turks

against the Sultan. The army had mutinies by soldiers who were never paid

and who were mistreated by the officers; mutinies by officers who were

also never paid and who were never given promotions based on service or merit; and uprisings by civilians who took the opportunity to attack

corrupt civil servants and governors while army mutinies occurred. | ||

|

Part 2:

Resuscitating the sick man |

|

Testing the 'Sick Man of Europe' It was therefore not a coincidence that his declaration of independence coincided directly with the announcement on 6 October that Austria-Hungary was formally annexing the vilayet of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Serbia raised an even louder protest than did the Turkish government, and Russia joined in the protests only after it was clear that Vienna would not support Russian designs on opening the Straits to Russian warships. The revolution faced its first great test but could only muster a Committee-inspired boycott of Austrian and Bulgarian goods. Sultan Abd-ul Hamid saw in the crisis a chance to regain supreme power. On 17 December 1908, he suspended the parliament and the constitution, declaring the "revolutionary experiment" a failure. The radical Islamic reaction was readying to strike against the revolution and its star pupil, Enver Bey. The Counterrevolution Salonika was the headquarters of the Ottoman Third Corps, where Enver Bey had served, as well as the home of the revolution. Therefore, only its troops could be considered reliable enough to defend the revolution, and so it dispatched units into Constantinople under the self-proclaimed title of "Action Army" to suppress the recidivist Islamic movement of 13 April 1909, known as the March 31st incident. At their head rode Enver Bey, saber in hand, eager to defend Ottoman democracy from the reactionaries. The counterrevolution was staged by the madrasa, which were theological-scholastic schools that had benefited greatly under Abd-ul Hamid's patronage. Whipped up by the madrasa students and their supporters, the March 31st incident involved massacres of secular troops by the scholasticists, who demanded the abolition of everything not in conformity with Sharia law. The cunning Sultan was the silent director of this supposedly natural reaction to the secular heresies of the revolution. He retained his throne even as the Action Army swiftly crushed the reaction in Constantinople. Among the officers of the "Action Army" suppressing that outbreak were also Mustafa Kemal and Omer Seyfettin. But the counterrevolution spread beyond the confines of the Third Corps, reaching Adana in late April 1909, where the madrasa fanatics turned anger over their defeat against the Armenians, whose Hunchak party was among the most vocal supporters of the 1908 revolution. Tens of thousands of Armenians were slaughtered in the event, and thousands of buildings were burned in the conflagration that spread from the fighting. Ottoman troops put down the revolt with even more bloodshed. Contrary to popular belief, the Committee was supportive of the Armenian cause, and Jemal Bey was appointed vali of Adana. He organized aid and shelter for the survivors, and the Armenians considered him their closest ally. (Within six years, however, Jemal's name would be tied to the Armenians in quite a different way.) As retribution for secretly supporting the madrasa revolts, Sultan Abd-ul Hamid was forced to abdicate on 27 April 1909. He was replaced by his brother Reshad ed-din, who had been imprisoned in the harems for 30 years. During this crisis, the Ottoman government had settled with Bulgaria, recognizing its independence, and also giving recognition to the Austrian annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina in exchange for a cash payment of 2.2 million pounds on 27 February 1909. The whole affair served to raise the popularity of Enver Bey and his Committee fellows, but the Committee's representation in parliament was never large enough to attain power. They had only 60 out of 220 seats in 1908. They would have to wait for an even bigger crisis in order to secure complete power. Turan, The Foundation of a New Order The "Turk" was more of a state of mind

rather than a racial quality. The true Turanian could not be defined by

racial features. During the Republic, Kemal Atatürk would proclaim the

ancient Hittites to be his people's true ancestors. Hittites were not

Turanians. None of the Turkish people could claim anything greater than 25

percent Turanian blood. The rest was Greek and Armenian, according to the

vast population of both peoples who lived in Anatolia when the Turks first occupied parts of the Byzantine Empire in 1085. However, none of this mattered to the budding Turan movement. |

||

|

The

Players 1: The big leaders |

|

|

|

||||

| Talaat

Pasha, one of the

Triumvirate. He first became chief of the Ottoman Postal Service, but then

led the Young Turks' putsch in 1913. He then became Grand Vizier and

undisputed strongman of the Ottoman Empire. He was known as one of the

most affable gentlemen to ever seize power in a bloody rampage. His

gentlemanly, likeable demeanor could only be spoiled by news of a

catastrophe in the war or else by simply mentioning the Armenians, as the

American Ambassador Henry Morgenthau discovered. Talaat was the real

strongman in the Ottoman Empire. He was the mouth and fist of the unseen

Committee, and he was the one who appointed Enver as War Minister and

Jemal as Navy Minister. His personal leanings were neither toward the

Entente nor toward Germany. He distrusted all parties, but at the

beginning of the World War, he felt more comfortable on the side of the

Germans, who were fighting the Turks' hated enemy, Russia. Before 1913,

Talaat trusted Great Britain as the protector of the Turks, but this was

thrown out the window when Britain joined Russia in a war to destroy

Germany. With Russia yearning for Constantinople as its glorious

Mediterranean naval base of Tsar grad (the Romanov's intended name for Constantinople), it was little wonder that Talaat was

swayed by Enver. On 2 August 1914, Talaat approved of a secret military

alliance between Germany and the Ottoman Empire. Six months later, he was giving orders to the vilayet governors to deal with the traitorous peoples in their midst; by which he meant the Armenians, of course. GWS, 11/01 [rev. 2/08] |

Jemal Pasha, one of the Triumvirate. He first came into the

world's knowledge when he served as governor of the Adana Vilayet

following the Armenian massacres there in 1909. For his work in rebuilding

the damage and salvaging the Armenians' livelihood, he was actually

remembered fondly there. He became the Ottoman Minister of the Navy after

the Young Turks' putsch in 1913. Jemal pushed for the purchase of the

Goeben and Breslau in August 1914, as World War I was starting. This

action helped turn the Turks toward the Central Powers in the war. What is

bizarre about this is that Jemal was actually pro-Entente at the start of

the World War. As the French ministers left Constantinople, Jemal wished

them victory in the war. His interest in the two German ships may

therefore be construed more as a means of strengthening the navy, his

chief concern at that time. For, the British in early August had announced

the seizure of two cruisers that Turkey had ordered and mostly paid for.

This drove Jemal to strike a bargain with the Germans, and in turn gave

Enver additional support in turning his friend toward the Teutons. Jemal's

former reputation as a benefactor turned sour as he became

governor-general in early 1915 of the Syrian Vilayets, which stretched

from Aleppo to Aden. The murderous deportations of Armenians from the

Eastern Vilayets to Mesopotamia and Syria occurred under his governorship,

and the deprivations that caused the word "genocide" to enter common usage

may be blamed on him. GWS, 11/01 [rev. 2/03] |

Sultan Mohammed V, born Reshad, who was installed by

the Young Turks in place of his older brother Abd-ul Hamid II in 1909. He

played no role in the government, confined to issuing Young Turk fetvas

and ulemas in his own name. Mohammed V is generally regarded by history as

being a moronic imbecile, with a tendency to drool. According to The Near

East from Within: "The very appearance of Mahomet V suggests nonentity.

Small and bent, with sunken eyes and deeply lined face, an obesity

savoring of disease, and a yellow, oily complexion, it certainly is not

prepossessing. There is little or no intelligence in his countenance, and

he never lost a haunted, frightening look, as if dreading to find an

assassin lurking in some dark corner ready to strike and kill him ...

Abdul Hamid hated and despised him, but was afraid to have him killed,

perhaps through fear that a stronger man might take his place." A story

goes that shortly after Abd-ul Hamid II was confirmed Sultan, all his

brothers were imprisoned in the traditional Ottoman way [soft palaces and

seraglios], to stifle rival claimants to the throne. This was the

traditional way of the house of Osman. Originally, the brothers of the

Sultan were executed, this being performed from the time of Mohammed the

Conqueror in 1451 up to Selim the Grim in the 1590s. However, from the

XVII. Century, Sultans preferred to imprison their siblings. Being locked

away for decades had the tendency of weakening the mind, and indeed, the

Ottoman history is rife with crazed and insane Sultans who were simply the

puppets of the Janissaries. Thus, this tradition was quite a reasonable

explanation for the downfall of the Ottomans. By 1909, the Janissaries

were long gone, but Mohammed V remained. He had been imprisoned for 30

years in the imperial harem, which might have seemed a most desirable

prison. However, it had the effect of making him quite effeminate and

weak. Thus, his rule was of such a state that when Ambassador Morgenthau

was leaving, the Sultan lamented to him that "had it not been for the

Russians attacking us, we would never be in this war." Morgenthau was

saddened at how the Young Turks had misguided the old Sultan into

believing the Russians had wronged him, when in fact Turkish-owned

cruisers had been the aggressors. Simple though the Sultan might have been

in political affairs, he was recognized as a brilliant poet of the old

Persian style. In fact, much news was made of the Sultan's formal poetic

presentation to Enver Pasha of a poem celebrating the Turks' brilliant

victories in Gallipoli. Surely, it was a talent he perfected during his

years of imprisonment in the harems. The Sultan was not the complete

drooling imbecile that many observers relished describing. His confinement

of thirty years, nine of them alone in the harems, had given him the

opportunity to study not only Persian poetry but also many other subjects,

and it happened that the Sultan was well-read even in science and imbued

with knowledge and wisdom that unfortunately served nobody while he was

the pawn of the Young Turks. GWS, 11/01 [rev. 2/03] |

|

Part 3:

Janissaries are reborn |

|

In 1909, with both the Islamic counterrevolution successfully thwarted and the Committee out of power, Enver traveled to Germany as a military attache. He learned to speak German fluently, and when he returned to Constantinople in 1911, he bore a waxed moustache slightly curled up at the ends, emulating the Prussian style of Kaiser Wilhelm. In his private conversations, Enver made no secret of his admiration for Germany, and his future elevation to the Ministry of War would be a boon for the Kaiser. However, before the young officer could seize the mantle and become the all-highest warlord of the Sultan and Caliph ul-Islam, he would have to prove himself in several very serious military tests. Tripoli in 1911, the First Debacle The Marchese di San Giuliano may have been the

craftiest and most intelligent Foreign Minister Italy or any other country

ever had. He announced to the Lower Chamber in Rome on 2 December 1910, "We

desire the integrity of the Ottoman Empire and we wish Tripoli always to

remain Turkish." About nine months later, San Giuliano notified the

Great Powers of his intention of occupying the African provinces of the

Ottoman Empire. None of the Powers raised objections, because there was

little of value there and most wanted Italy to focus away from the Balkan

peninsula where its claims could cause trouble. Albania and Yemen in 1912, the Next Debacle By

spring 1912, the Italians were desperate for new battlefronts to bring a

decision to the bloody, drawn-out affair in Africa. Austria-Hungary in particular

placed a veto on Italian military action against the Turks in the Balkans,

fearful of stirring up more trouble than there already was there. Egged on by the wily King Nikola of Montenegro (read about it in Ambassador Wladimir Giesl's biography), the

Catholic malissori tribe of Albanians in the north had clashed with the

Turks in early 1911 and Italy had been their main source of arms. Since

the beginning of the Italo-Turkish War, other tribes had joined the

rebellion of the malissori, and the Turkish War Minister ordered more troops into Albania to

fight the insurgents than were fighting the Italians in Tripoli. This

rebellion would stretch through 1912 until the late summer, when Italy

brought the war to the Dardanelles with its warships and occupied the

Dodecanese Islands to force the Turks to accept the fall of Tripoli. The First Balkan War in Autumn 1912, a Very Serious Debacle When Montenegro's king Nikola ceremoniously fired the first shot of

the war on 8 October 1912, he had only been invited to join the alliance a few days before by Russia, whose Foreign Ministry had been at the center of the

conspiracy against the Ottomans. Enver's response was to advise settlement

with Italy as soon as possible, and War Ministry agreed. The Treaty of Ouchy, signed in mid-October

1912, gave the Italians all that they had fought for, except outright

annexation. To keep with the claim by the Marchese di San Giuliano in 1910

that Italy desired Tripoli to remain part of the Ottoman Empire forever,

the peace treaty reaffirmed the Sultan's religious and de jure authority

over Tripoli's inhabitants. It did not grant such a privilege to the king

of Italy. The Second Balkan War in March 1913, a Contrived Debacle After the Grand Vizier Nazim Pasha had signed an armistice with the Balkan States on 12 December 1912 , leaving the three heroic, still-besieged cities of Scutari, Jannina, and Adrianople to the victors, Enver Bey led the putsch against the government on 9 February 1913. Nazim was killed and the Committee was placed in full control of the Empire. Enver had the peace treaty torn up, and on 16 February, hailed the imminent relief of Adrianople under his command! However, this new war (rarely but properly called the Second Balkan War) was short. Enver personally led the charge against the Bulgarian trenches along the Chatalja Lines, and promptly came to an embarrassing halt after two days of bloody struggle. Adrianople could not be relieved and it surrendered under a sustained bombardment by Russian-loaned cannon on 26 March. Of the other besieged cities, Jannina had never really been given a moment's rest by the Greek army, and it fell on 6 March 1913, while the relatively light siege of Scutari by the Montenegrins was beefed up by the Serbians, and it finally fell on 22 April. Turkey was totally defeated in Europe, and the armistice terms of December reacknowledged by the Committee. The belligerents finally signed the peace Treaty of London on 17 May 1913. This humiliating episode at least served to bring the Committee back into power after a four-year absence. The Third Balkan War in July 1913, Not a Debacle but Not Glorious, Either

In the Third (almost always called the Second) Balkan War that began on 1 July 1913, Tsar Ferdinand of Bulgaria took matters into his own hands and attacked his Serbian ally in order to win Macedonia, the prize for which Bulgaria had marched to war but had been denied. Herein lay an opportunity for revenge! With the hated Enos-Midian Line evacuated by the Bulgarians, who were suffering major setbacks by the Serbians, Enver rode all night long at the head of his army to the very gates of Adrianople. By the time they arrived on the morning of 23 July 1913, the Bulgars had already abandoned the city, and Adrianople had been won without battle. Nevertheless, the occasion sealed his reputation as a victorious commander as much as Tripoli had given him a reputation of competence and determination. He was more than happy to receive laurels from the people, and was awarded the honorable title "Pasha" from the Sultan. Postage stamps were even printed to celebrate the victory of Adrianople. How Enver Came to Rule the Ottoman Army in January 1914, a Humorous Debacle

In January 1914, Enver took a leap with the Committee's approval and increased his power significantly. Izzet Pasha, the Turkish Minister of War, was sick and failed to appear at his office. Enver suddenly showed up at the office in a general's uniform and declared that he was the new Minister of War. Clearly, it was the doing of the Committee, for Izzet Pasha did not challenge this brazen usurpation. Nor did the Sultan, who read about his new Minister of War in the morning newspaper, and reportedly said, "It is stated here that Enver has become Minister of War... That is unthinkable. He is much too young!" Al Hasa in 1914, the Forgotten Debacle As if to test the resolve of a weakened enemy who appeared to surrender on all terms, Wali Abd-ul Aziz ibn Abd-ul Rahman al Saud, ruler of the Nejd, sent a contingent of horsemen across the desert from Riyadh in early winter 1914 and approached Dahran on the Persian Gulf. They surprised the Turkish garrison, which surrendered without offering resistance. News of Saud's coup de main was wired by the British attache from Bahrein, and the British ambassador personally informed Enver of the stunning development. World War I in Autumn 1914, the Final Debacle As summer drew on, Enver was desperate to complete the Army reforms. He organized German support to build up the officer corps which he had decimated during the winter, and caused a diplomatic scandal of epic proportions when he designated German General Otto Liman von Sanders as Commanders of the Turkish First Corps at Constantinople. Only months of political wrangling and much sabre-rattling by the Great Powers succeeded in confirming his choice. The episode illustrated both Enver's political naivete and his stern determination. GWS, 2/03 [rev. 4/08] |

||

|

The

Players 2: Germans commanding Turkish armies |

|

|

|

||||

Colmar von der Goltz, originally sent to Turkey in 1881, but in command of the Mesopotamian Front until his death in 1916, either from Typhus or from poisoning... |

Otto Liman von Sanders, sent to Constantinople in January 1914 to command the I. Army in the city; later made chief of all operations during the Gallipoli campaign. | Friedrich Kress von Kressstein, directed the ill-fated Turkish IV. Army in its assault on the Suez Canal in early 1915, and then defended Gaza until its fall in late 1917. |

|

Germans who Commanded Turkish

Armies | ||

|

Quite a few Germans served their Turkish Allies by commanding Turkish armies. There had been a tradition of cooperation between the Prussians and the Turks dating back to 1842, when, following first a long struggle against rebellious Mohammed Ali of Egypt and then the humiliating Protection Treaty with Russia in 1840, the tired, devastated Ottoman army needed true European reform. Moltke and other Prussian officers lent their expertise to bring the Ottoman armies out of the middle ages with their janissary techniques. By the 1880s, a new round of Prussian-German officers were serving in the Ottoman army as advisors following the difficult Russo-Turkish War. Colmar von der Goltz was the senior advisor, and his return to Turkey in 1915 was welcomed by Enver Pasha. The Germans invested even more in the new Ottoman Empire following the revolution of 1908, but once the Balkan wars caused the Turks to be expelled from Europe, the Entente press mocked the years of German military training for its poor results on the battlefield. The problem was not in the German training, but in the failure of the Turkish military to successfully juxtapose Turkish oriental habits with the strict European method. The upper class of Ottoman princes who made up the officers were the biggest problem, but also infighting and abuse among the NCOs were a substantial problem. Furthermore, there was no way for the German advisors to improve the infrastructure surrounding the army. Transportation and communication was as big a problem in 1912 as it was in 1842, and would still be so in 1918, when the famed Berlin-to-Baghdad Railway still had not been completed. International trouble occurred in January 1914 when Enver Pasha appointed German General Otto Liman von Sanders as commander of the Turkish I. Corps in Constantinople. Russia objected loudly to a German officer having total military control over the Straits. A long process of diplomatic negotiation finally melted the Russian resolve and they allowed the German general to remain in place. In spring 1915, six months after Turkey declared war on Russia, Liman von Sanders was in the right place to organize resistance to the invasion of Gallipoli by the Entente.

|

|

The

Players 3: Rulers caught in Enver's war

aims |

|

|

|

||||

| Khedive Abbas Hilmi, son of the flamboyant spender Khedive Ismail. Abbas Hilmi ruled Egypt from 1892 until October 1914. He happened to be visiting Constantinople, paying homage to the Ottoman Sultan right at the time Enver decided to declare war on Russia. Britain responded to this by staging a putsch in Cairo, arresting the entire Egyptian government. London declared the ancient suzerainty of the Turks ended and formalized their protectorate. Abbas Hilmi remained in Constantinople during the entire war and beyond. He died in 1944. GWS, 3/04 |

Khedive Hussein Kamel, the first and last Sultan of Egypt. Hussein Kamel was the uncle of Egypt's Khedive Abbas Hilmi. When the Turks declared war, Abbas was in Constantinople and consequently lost his rulership over Egypt. The British appointed Hussein Kamel as a known loyal friend of England. He assumed the title "Sultan" of Egypt instead of Khedive, since such a title implied both a challenge to the legitimacy of Abbas Hilmi and also suzerainty to the Ottomans. His reign did not last long, for in 1918, Sultan Hussein Kamel died and was succeeded by his son Farouk. GWS, 3/04 |

Prince Salar ed-dauleh, the leader of the Kashkai in southwestern Persia. Enver quickly contacted this opportunist with the plan to conquer Persia for the Ottoman Empire. Now, Persia was already occupied by Russian and British police and troops. These grated on the nerves of the Persian people, whose revolution was foiled by foreign interference. Salar ed-dauleh, who was wanted by the British for instigating trouble throughout Tangistan province, was hired by Enver's special German agent Wassmuss to raise a native revolt against the British on Persian soil. This was from 1915 until 1918. Salar was only partially successful; the British did not venture into the interior of Persia because of the danger, but neither did they leave their fortified positions at Bushire and in Arabistan. GWS, 3/04 |

Crazy adventures in Persia distracted the Ottomans from defending their own violated territories. Russians invaded deep into Anatolia, capturing Erzurum in 1916, as well as Van, Bitlis, and Mush. The British drove through Irak and into Mesopotamia, seizing Baghdad in January 1917, while Jerusalem fell in autumn 1917. In spite of a strong showing at Gallipoli during 1915 and the great victory at Kut in 1916, defeats outnumbered victories, and even the victories were achieved only with an enormous loss of lives and equipment. It seemed like every move by the Turkish Army had a terrible effect on morale. Enver himself traveled to Mecca with his uncle Halil Pasha during the hajj of 1915, and met with the Sherif Hussein and all of his sons, pressing the Arab leader to support the Sultan-Caliph's fetva for holy war. As T.E. Lawrence related in his book, while Enver Pasha was being entertained on the garden rooftop of the Sherif's palace, Hussein's younger son Abdullah pulled the Sherif to one side and asked his father, "Why do we not kill him now?" The Sherif answered, "Because, my son, the Pasha is a guest in our house. We cannot bring harm to him while he enjoys our hospitality." Afterward, Enver departed for Damascus, where his fellow Committee brother Jemal Pasha was already brutally suppressing Arab nationalists, and within six months, the Sherif Hussein raised the standard of revolt against the Ottomans! Arab rebellion swept through all of Hejaz until only the Turkish garrison of Medina remained, so completely cut off from the entire world, the garrison did not surrender until 13 January 1919, more than two months after the Ottoman Empire signed the armistice at Mudros. Of all the Arabs within the Ottoman Empire, only the Imam of Yemen remained loyal, aiding the Turkish garrison to invade Perim Island in the Straits of Aden (which was swiftly repulsed by the British) and pressing a three-year siege on the city of Lahej, whose Sultan begged for British protection against Turkish interference. Lahej was near the strategic port of Aden, which Enver declared would be captured at the same time as the Suez Canal, completing Britain's isolation from India. But neither goal was reached, adding to the Pasha's growing list of failures. Even as these setbacks tarnished Turkey's fighting reputation, Enver was desperate to prove to his allies, Germany in particular, just how competant his troops and officers were. This was not merely to elevate the rank of Turkey from a junior to senior partner in the Quadruple Alliance, but to extract further military concessions out of the Germans. Thus, 1917 saw the movement of a whole Corps from the Caucasian and Persian fronts to Galicia and Dobruja, where these troops were given the opportunity to show their fighting prowess far from the homeland. Enver personally selected the units that were sent to Galicia, and they formed the elite "Yilderim" or Lightning Corps. Only the finest soldiery with the best battlefield performance were allowed to make the journey to the trenches of what is now Western Ukraine and be part of Yilderim. They were outfitted with the best uniforms and new weaponry, to prove to the German HQ of the South Army that a highly technical military force was being sent to them. Enver did not want his allies to think he was delivering oriental savages to them. And what was the result of this demonstration? Practically nothing for either theTurks or the Germans. The arrival of the Yilderim Corps was a welcome insofar as any warm bodies counted on as massive sector as the Eastern Front. For Turkey, however, Enver's little gift to the Germans meant the best troops were far, far away from where they were really needed--on every invaded front. Turkish troops remained in Galicia until March 1918, when the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk ended the war between Russia and the Quadruple Alliance. Most of the troops were shipped to Samsun on the Black Sea coast. From there, most of "Yilderim" was sent to defend Damascus from the British advance, while the rest were marched to the Caucasus as the "Army of Islam" under Enver's brother Nuri Pasha, in order to fulfill Enver's dream of Turan. Everywhere, the Turks were in retreat, suffering from bad leadership, poor or nonexistent rations, exposure to frightful climate, and an ever-stronger enemy. Enver's glorious hopes were crumbling just as quickly, but he remained focused on Central Asia, even as he spent days in his offices by the Bosporus, or on long train trips to Berlin. Always Central Asia, and the mythical homeland called "Turan." |

|

Part 4:

Armenians are nothing to me |

|

|

Defending the Father of the Republic What role did Enver in Armenia's genocide? The modern Turkish Republic goes to great effort to counter Armenian charges of genocide. In fact, it seems that the fact that countless Armenians were killed and driven from their homes is not a contestable issue, but rather how and why the word "genocide" is used. For the story of Enver, the Ottoman government, and the tragedy of history, such discussion is pointless. There are two reasons for this, and both have to do with the Father of the Turkish Republic. One is that the Turkish Government should sternly defend the image of Mustafa Kemal Pasha (later Ataturk), who was intimately involved in the affairs and therefore the reputation of the Turkish Armies following the armistice in 1918. The Father of the Turkish Republic was responsible for ensuring that no Armenian resurgence should occur on Turkish soil, and therefore avidly supported all military action that deprived the Armenians of even territory that had been part of Russia before 1918, such as Kars, Ardahan, and Artvin. Two, the Turkish government has long defended the sanctity of Turkish territorial integrity. Admission of "genocide" would weaken Ankara's image and strengthen their enemies' resolve, especially the Kurds who make up a majority population of the former six eastern vilayets. The Turkish government is caught by its own unwillingness to define what precisely happened in the winter and spring of 1915. The Worst Winter or the Worst Scheme? Generally, the official line is that the winter of 1915 killed 150,000 or more Armenians, and an equal or greater number of Moslems. One may suppose its simply a continuation of 125 years of hostility between the two peoples. In 1878, the Treaty of Berlin, which made peace between Russia and the Porte, specified that certain reforms be made in the six eastern vilayets of Anatolia. These vilayets contained the majority of Turkey's Armenian subjects. The Porte never carried out these reforms, for the simple reason that to do so would inevitably reduce Ottoman sovereignty in a region where Armenians were actually a minority. In fact, the Armenians were not a majority in any of the towns of the six vilayets, except for Van. Mostly, the Armenian issue comes down to number games. As the official Turkish Embassy website states, "Demographic studies prove that prior to World War I, fewer than 1.5 million Armenians lived in the entire Ottoman Empire. Thus, allegations that more than 1.5 million Armenians from eastern Anatolia died must be false ... Reliable statistics demonstrate that slightly less than 600,000 Anatolian Armenians died during the war period of 1912-22 ... The statistics tell us that more than 2.5 million Anatolian Muslims also perished. Thus, the years 1912-1922 constitute a horrible period for humanity, not just for Armenians. The numbers do not tell us the exact manner of death of the citizens of Anatolia, regardless of ethnicity, who were caught up in both an international war and an intercommunal struggle. Documents of the time list intercommunal violence, forced migration of all ethnic groups, disease, and starvation as causes of death. Others died as a result of the same war-induced causes that ravaged all peoples during the period." This is perhaps the most interesting part, as "intercommunal violence" was indeed the key to the Armenian problem. Enver's invasion of Russia failed miserably in December 1914, when 70,000 Turkish soldiers were killed in the freezing mountain passes. The Russian army advanced across the Turkish border by the end of the month. Armenians were visibly overjoyed at the defeat of their persecutor's forces, and welcomed the Russians when they came, both verbally and violently. This is when "intercommunal violence" began. Sporadic murders and outbreaks of rebellion occurred in several towns, culminating in the expulsion of the Turkish garrison at Van in March 1915. As the official Turkish Embassy website explains, "between 1893 and 1915 Ottoman Armenians in eastern Anatolia rebelled against their government -- the Ottoman government -- and joined Armenian revolutionary groups, such as the notorious Dashnaks and Hunchaks." In reality, there were no widespread rebellions among the Armenians, but there were notorious bandits who were armed by the Russians and who attacked Ottoman authorities. Even Lev Trotsky wrote a few articles about Ottoman Armenian rebels and their Russian benefactors for Pravda and other socialist newspapers before the war, complaining of how the Romanov agents financed terrorism abroad in order to further imperial aims. The Turkish Embassy plainly admits this much: "The Armenians took arms against their own government. Their violent political aims, not their race, ethnicity or religion, rendered them subject to relocation." This is an academic admission that the Turkish authorities forcibly uprooted the Armenian population in the six vilayets. "On November 5, 1914, the President of the Armenian National Bureau in Tiflis declared to Czar Nicholas II, 'From all countries Armenians are hurrying to enter the ranks for the glorious Russian Army, with their blood to serve the victory of Russian arms. ... Let the Russian flag wave freely over the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus.' ... Boghos Nubar addressed a letter ... on January 30, 1919 confirming that the Armenians were indeed belligerents in World War I. He stated with pride, 'In the Caucasus, without mentioning the 150,000 Armenians in the Russian armies, about 50,000 Armenian volunteers under Andranik, Nazarbekoff, and others not only fought for four years for the cause of the Entente, but after the breakdown of Russia they were the only forces in the Caucasus to resist the advance of the Turks....'" A Task for the Governors? Enver's response? In February 1915, he wanted to dispatch parts of the Third Army against the Armenians and finish them off for good. Talaat had enough foresight to see military disaster in this, what with the Russian Armies already winning victories in the neighborhood, and urged his impetuous War Minister to let the Third Army do its job fighting the Russians. Instead, Talaat notified the valis of the vilayets to send local contingents to quell the violence. That is, no regular soldiers, since these were needed for the war effort. The valis baited Kurdish irregulars into the Armenian settlements with incentives to meet two objectives: defeat the rebellion and put the population on the move away from the war zone. In this way, depopulation occurred, as well as starvation and mass murder. The death marches to Mesopotamia and Syria were a matter for the civil government to handle, since they were the ones ordering it. Jemal Pasha, who was appointed governor of Greater Syria during the war, found himself burdened with an order to handle thousands of deportees being marched into Syria from the north. This territory was uniquely inhospitable and Jemal must have known this order to be a death sentence for all involved. The issue is whether Enver, Talaat, Jemal, and the governors planned this as a death march for the population. If the horrific deaths were a matter of poor supply and transportation in times of war, then the word "genocide" cannot be used as effectively as, say, if Enver and Talaat met in a dark room and plotted the deaths of all Armenians. The permanent removal of all Armenians from the six eastern vilayets was inevitable at this time, as the risk of an untrustworthy segment of the population was not going to be tolerated by a hard-pressed authority like the Ottomans. This was illustrated in January 1915, when the Armenians of Van rose in rebellion and expelled the Turkish troops. They invited the Russians as protectors, but General Izzet Pasha ordered a counteroffensive against Van in the spring, resulting in a defeat for the Russians. As the Russians retreated from Van, the entire Armenian population of some 50,000 also abandoned their homes, and the ancient city was totally destroyed in the fighting. These Armenians never returned home, but scrounged a meager existence in horrendous refugee camps throughout southern Russia. Similar things happened on the Turkish side of the battlezone. First the Kurds, under orders from the Turkish valis, expelled Armenians close to the battlefield. Kurds today freely admit that their grandfathers expelled the Armenians and took their homes for themselves. Then the Kurds themselves had to flee as the Russians advanced deep into Anatolia. By the time the war had ended on the Caucasus front in MArch 1918, most towns were totally destroyed, and empty except for a few who weathered the Russian occupation. Kurds are surprisingly honest in their role in the Armenian issue, since they have no friends among the Turks, whose civil governors urged them to turn on the Armenians... Turks who later turned against the Kurds themselves. Clearing the battlefield of all Armenians because of their likely support for the enemy was reason enough for the deportations, and Entente complaints throughout the year 1915 were shot back with claims that this was "an internal affair." Meaning, Armenians resisting deportation were rebels and not entitled to any international protection accorded soldiers. Of course, British General Townsend, who surrendered at Kut in 1916, met with a death march of his own through the brutal Iraki desert. If half of his "internationally protected" soldiers died of thirst, exposure, and savage abuse on their way north, what percentage of "unprotected" Armenians would have perished being force-marched south? Such cruelty must be left to the imagination, which is why the Armenian Genocide issue is still controversial and will always be so. Conspiring with the Enemy? Edessa in early 1916 was a particularly dramatic scene, where the Armenian community barricaded itself in the old city as Turkish cannon were brought to the scene to bombard the walls. Finally, the German commander of the Mesopotamian Front, General Colmar von der Goltz, negotiated the surrender of the community with guarantees that they would not be deported. Unfortunately, the Turkish vali of Edessa turned on the Armenians upon their surrender, and deported them all. Von der Goltz was scandalized in the Entente newspapers for taking part in the tragedy. In the same year, the Armenians of Lattakia, on the Syrian coast, fled to the mountain of Muzdagh, and held off a Turkish battalion for several months before French steamers landed on the shores just long enough to rescue the besieged defenders of the mountain. Such actions merely confirmed the suspicions of the Ottoman government that some sort of complicity existed between the Armenian community and the Entente. Turkish Armenia was not the only place to suffer. As soon as the battle of Sarikamish foiled the Turkish invasion of Russia, Enver ordered the invasion of Persia to find an alternate path to victory. In reality, the campaign in Persia was a resource-wasting effort that gained the Ottomans nothing, but fueled Enver's dream of unifying the Turkic peoples of the world. He was pleased that the Azerbaijanis, Kashkai, Turkomans, Lurs, and Kurds of northern Persia welcomed the arrival of the Turkish Army. Of course, that may be a result of ten years of humiliating Russian occupation. From 1915, the Armenian community in the Urmia-Dilman region was devastated. Turks state that the local peoples turned against the Armenians because the Russians favored them, but there is no evidence of favorable treatment of any group in northern Persia by the Russians. Prince Sharraf Khan, a Kurdish leader, took the banner of religious war against the Russians, and gleefully entered the ranks of the Turkish army. However, his troops were more adept at running Armenians and others from their homes than battling hardened Russian troops. Armenians and the Treaties: Brest-Litovsk, Batum, Mudros, Sevres, Lausanne In June 1918, the representatives of the three Transcaucasian governments were invited to Constantinople to ratify the Treaty of Batum, which had been drawn up by Talaat's government in April in order to normalize relations between the Porte and these states. It must have been a moment of supreme irony as Talaat Pasha welcomed the Armenian plenipotentiary Avedis Aharonian into his office. Aharonian made the journey to protest the onerous terms of Batum, which relegated the Armenian republic to some 4,000 square kilometers, basically the capital Erivan, Lake Sevan, and Alexandropol. Erivan itself was a border town. The small state could not care for itself, and the mountains were covered with refugee camps, most of whose inhabitants lived in the areas the Treaty of Batum had assigned to Turkey or Azerbaijan. By the Treaty, the Ottoman Empire had annexed one half of the Batum-to-Baku railway system, including Batum, Kars, Ardahan, Artvin, more than one-half of the Erivan province, and Nakhichevan. Azerbaijan was granted the other half of the line, from Zangezur all the way to the Caspian. Enver in particular had demanded these borders, so that his Army of Islam, under the command of his brother Nuri, would have a direct access to Baku and to the Turanian lands on the other side of the Caspian Sea. The Armenian plenipotentiary met with several Ottoman and Committee members during his visit, including Enver. Aharonian reported that Talaat was polite, but denied all involvement in the Armenian massacres. He wove away the issue with his hand, and blamed any excesses on the Kurds, on corrupt local officials, and on the Russian army. Aharonian later met with Sultan Mohammed VI, who was quite frank about the Armenian tragedy and lamented their treatment by the Turkish authorities, adding he hoped that many of the Committee members could be replaced soon. Aharonian considered Enver to be the most congenial of them all. He was courteous and gracious, even friendly. However, he would not budge on the issue of the Treaty of Batum or the refugee situation. He explained to Aharonian just how important the Batum-to-Baku railway was to Turkish interests, and that it was a large measure of trust that the Porte even allowed a miniature Armenian state to exist. Finally, Enver advised the Armenian government to clear out of Tiflis, Georgia (where it had been situated since the revolution) while it still had a chance. They were to go to Erivan, which was a refugee-choked backwater compared to urban, civilized Tiflis. The Batum-to-Baku railway's importance was more than just Enver's fantasy. Earlier in that same month, the Georgian government had signed an alliance with Germany, placing itself in their protection. As Aharonian was preparing to leave Constantinople, he took the Georgian plenipotentiary aside and bitterly complained about the alliance, since it basically left Armenia squarely in Turkey's hostile arms. The Georgian diplomat defended himself by saying that Armenia would have done the same thing if it was in Georgia's place. Talaat was already bristling with bitter hatred for Germany over their Georgian alliance, which he considered treasonous, as well as Germany's interference in the affairs of the Crimea, which Talaat claimed for the Porte (for details, see Suleiman Sulkevich's biography).The Germans landed troops at Poti in Georgia in summer 1918 to stake their claim in the Caucasus, but the Treaty of Batum prevented them from dealing with Armenia, except to wrangle with the Porte over certain territories claimed by both Georgia and Armenia. The Armenians simply waited for the war to conclude, as they were clearly powerless in their own country. Enver's brother Nuri did reach Baku, and saw to the expulsion of the small British force under Colonel Dunsterville that temporarily occupied the city. Nuri's troops joined the local Azerbaijanis and committed a massacre of Armenians throughout the city, although one wonders just how many Armenians chose to remain in Baku after the British fled.In spite of Turkish troops washing their boots in the warm Caspian Sea, Enver's connection to the mythical Turanian lands beyond the bright blue horizon was never made, and by 30 October 1918, when the armistice treaty was signed at Mudros, Nuri evacuated his Army of Islam from Baku, while the rest of the Ottoman army marched out of northern Persia in the wake of the British advance on Mosul in northern Mesopotamia and on Aleppo in northern Syria. The war was over. Almost. The Committee for Union and Progress collapsed, and Talaat fled to Berlin, followed by Jemal and Enver. The Armenians attempted to fill in a "power vacuum" in eastern Anatolia, but in reality there was none. Remnants of Nuri Pasha's Army of Islam reoccupied all of Turkish Armenia and returned most of the refugees--except for the Armenians who, for various reasons, no longer existed. When the Armenian forces marched from Erivan, they were able to seize Kars, but nothing beyond the old Turkish frontier. Their lobby in the west was quite vocal, however. As compensation for the massacres and deportations during the war, the Armenian delegations to the Peace councils and western capitals demanded the six eastern vilayets as part of the new Armenia. Only problem was, the Armenians were too weak to take these areas militarily, there were no longer any Armenians living in these areas (much less those who once lived there were a minority), and none of the western powers wanted the responsibility of occupation. Only the British were interested in securing the Batum-to-Baku railway, recalling Colonel Dunsterville from the deserts of Turkestan whence he had retreated. First he reoccupied Baku, and then traveled the railway to Batum, occupying a portion of the western railway on behalf of the Armenian republic, whose forces were being challenged by the much enlarged Azerbaijani army. When Nuri Pasha left Baku, he did quite the same thing Enver had done in Tripoli seven years earlier: he permitted soldiers and officers of his Army of Islam to join the Azerbaijan's national army, providing they received pay and rations. From then on, Armenia was outclassed by Azerbaijan, and sporadic but heavy fighting over the Nakhichevan, Zangezur, and Karabakh regions did not really end until the Red Army laid both countries low in 1920-1921.Meanwhile, in winter and spring 1919, Mustafa Kemal Pasha led a series of swift offensives against raids by the Armenians, and seized Kars, Artvin, and Ardahan (briefly part of Georgia). Armenia was henceforth exclusively in the old Russian territory, not the Turkish. The infamous Treaty of Sevres of 1920 arranged for an Armenian state with territories carved from the six vilayets, but of course there was no great power willing to enforce the treaty's terms. When the subsequent Treaty of Lausanne was signed by Kemal's government in 1923, Armenia no longer existed. A deal was struck between Kemal and Soviet Russia, ensuring the question should not be raised in the future. Did Enver Pasha plot and carry out

genocide against the Armenians? Evidence shows he desired a brutal military suppression of the Armenian rebels, but he

personally had more to do with the misery of the Turkish army and less

to do with the misery of inhabitants of Anatolia, except that it

was he who brought war to them all in the first place! |

||

|

The

Players 4: Picking up the pieces |

|

||||||

| Halil Pasha, Enver's uncle and general in the Turkish army. He was also an early and influential member of the Committee for Union and Progress. Like most political parties of the time, the Committee's doings were not for the general public. Indeed, they met in secret, in a closed, windowless room in an unnamed villa in Constantinople. The entire leadership never once assembled congress-style, even though they all lived in the same city. It is difficult to ascertain whether Halil influenced his nephew Enver, or the other way around. Certainly, being related to the young and dashing "hero of the revolution" was very helpful for Halil's military career, as well as bringing him to the top of the Committee's leadership posts. On the other hand, it is questionable if Enver could have risen to the absolute heights of popularity and influence within the army had it not been for his uncle Halil's established and respectable connections. After the putsch of February 1913, Halil was granted various positions in the government, including being the Caliph's official leader of the last great hajj to Mecca in 1915. He was an active general in the war, and conducted several operations in Persia with varying success. In 1918, his force paralleled the movements of his other nephew, Enver's brother Nuri Pasha, who commanded the "Army of Islam." Halil's brother Ahmet, who was Enver's and Nuri's father, also had a position of power in the Turkish force that marched to Baku. In December 1919, General Arthur Gough-Calthorpe, the British general in charge of the occupation of Constantinople and the Straits, ordered the "Army of Islam" out of Baku, and recalled General Dunsterville from Turkestan to trail them. Among those to be expelled from the Transcaucasus were "one Nuri Pasha, Ahmet the father of Enver Pasha, and his brother Halil." After the war, Halil maintained strong connections with his nephew, even visiting Russia as an emissary of the Nationalist government under Mustafa Kemal Pasha. However, in May 1921, Halil was arrested and sentenced to death for leading a bolshevik putsch against Kemal. Two other so-called bolshevik usurpers were also condemned, and this was a particular low point in relations between Soviet Russia and Nationalist Turkey. On news of his uncle condemnation, Enver publicly stated he was ready to lead a Red Army into Turkey and bring both revolution to the people as well as save his uncle. Kemal Pasha spared Halil from the death penalty, however, and charges were later dropped. A payback, perhaps, for Halil once saving Kemal from Enver's deadly plot? GWS, 3/01 [rev. 4/08] |

Mohammed VI, the last Sultan. He was born Vahid-ed-din, younger brother of Abd-ul Hamid II. He was spared imprisonment in the Harems, unlike his older brother who was to become Sultan Mohammed V. Vahid-ed-din traveled abroad and gained a knowledge of the outside world and also a desire to improve conditions within the Ottoman Empire. He was an idealistic visionary, but he came to the throne in the midst of the Empire's death throes, too late to have any positive effect. The sorry condition of the state as the war wound down filled the new Sultan with melancholy and then depression. He became bitter and antagonistic. He also became afraid both for himself and for his 700 year-old dynasty. When the time came for peace, the triumvirate of Enver, Talaat, and Jemal beat a hasty retreat to Germany and whichever other places that would grant them asylum. This suddenly left the formerly powerless figurehead Sultan in complete control of the situation, and his new Grand Vizier issued warrants for the triumvirate's arrest on charges of war crimes. However, overwhelmed as he was by the superior force of the Entente's advancing armies, the Sultan capitulated in every way to his enemies' demands. The British and French quickly understood just how beaten their royal foe was, and took more than an advantage over him. The Entente began to violate one armistice agreement after another, and used threats and ultimata to force the weakened Sultan to do their bidding. After they unlawfully occupied Constantinople, the Entente considered expelling the Sultan to Konia, that their control over the Straits would not be impeded by even the symbolic sovereignty of the Turkish ruler. However, they considered that a banished Sultan deep in the heart of Anatolia might become a rallying point for Turkish resistance. Therefore, the Entente made him a virtual prisoner in his sumptuous palace of Yildiz, and even posted British and French troops as guards around the palace grounds. The Nationalists were meanwhile gathering their forces together in Anatolia, and at first swore allegiance to the Sultan. Mohammed VI worried that the Nationalists were antagonizing the Entente, and considered that the Greeks and Armenians would be given free reign over the Turkish nation in response. He therefore expelled men such as Kemal Pasha from the army and ordered their arrest. This only had the effect of turning the Nationalist cause away from defending the ancient dynasty of Osman and also the Caliphate. GWS, 3/01 [rev. 4/08] |

Mustafa Kemal Pasha, the hero of Gallipoli, the stealer of Enver's glory. Here, he is photographed after his victory over the Greeks in 1923. Mustafa Kemal was actively involved the revolution of 1908, but criticized the Committee's involvement in army affairs. According to Enver Pasha's uncle, General Halil (see biography on this page), Enver asked Halil to have one of the committee brothers assassinate Kemal for his "dangerous anti-revolutionary behavior." Halil chose to ignore the request, and claims that Kemal never forgot him for saving his life. (It may be true, especially fifteen years later, when Halil himself was sentenced to death for plotting against the Nationalist government, but spared by Kemal.) Now, Kemal struggled to a respectable position under Enver's indomitable shadow, as the young War Minister was propagandized as the all-highest warlord of the revived Ottoman war machine. It took a horrific failure such as Sarikamish in December 1914 for Enver's shadow to recede, and a great victory in Gallipoli for the sun to shine in Kemal's direction. Yet, Kemal did not receive his just recognition even after his glorious triumph, so jealous was Enver of his reputation. Kemal was sidelined in the Turkish press, and the War Minister trumpeted his Yilderim or "Lightning Corps" as the new modern Turkish attack force. Still, the weight of more and more defeats shortened Enver's shadow, and the armistice of Mudros on 30 October 1918 wiped it away altogether. Kemal became well-known to the Turks only after he succeeded in preserving the core of the Turkish army, defying the Sultan and the Entente, and bringing destruction to the Armenians and Greeks in Anatolia. True modern Turkish nationalism was literally invented by Kemal, and it is fitting that he chose for himself the name Atatürk, which means "Father of the Turks." GWS, 12/00 [rev. 4/08] |

|

Part 5:

Lost in the wilderness |

|

Enver departed from Constantinople shortly before

the occupation of the capital by the joint British, French, and Italian

forces in November 1918, after the Armistice. Only the end of the war

opened the Straits to the Allied Fleets. Enver, the King of Kurdistan, condemned to death for war crimes! The new Ottoman government under Izzet Pasha convened a tribune in July 1919, finding the chief members of the Committee guilty of war crimes. Talaat, Jemal, and Enver were condemned to death. But Enver was already living Berlin under the assumed name "Ali Bey" after a circuitous route through the Ukraine with German troops who were leaving Turkey. Enver was good friends with General von Seeckt, who was chief of Staff for the Southeastern Front in 1917, and the two had met on several occasions while Turkish troops were on loan to Seeckt's command. Once Seeckt became chief of staff for the much reduced German Reichswehr, he might have found some use for his undercover friend with international connections. And yet, 1919 was a chaotic period for the disheartened war minister. Rumors ruled more than truths. While "Ali Bey" the refugee eked a mundane existence at the will of General Seeckt and sympathetic committee members in hiding, "Enver Pasha" the notorious war criminal was seen everywhere. He was reportedly arrested and thrown into a German prison, awaiting extradition to Constantinople for a war crimes trial! He was reported to have fled arrest in Berlin and taken refuge in the Caucasus, protected by wild bands of Tartars who had fought in his brother's "Army of Islam!" He was reported to have abducted by Nationalist agents and smuggled back to Angora so that he couldn't overthrow Mustafa Kemal's Nationalist Congress! He was reportedly crowned the King of Kurdistan, and was preparing his two million fanatical subjects for an invasion of Central Asia to build the new caliphate with himself as the heir to the Prophet Mohammed! He was supposed to seize power in Baku, unify the Turanian peoples, and then ally himself with mad General Semyonov, who was supposed to control Mongolia and Siberia, and together they would turn Central and North Asia's undeveloped agricultural potential over to the Japanese, who would end western dominance in Asia once and for all by curbing the global food supply! In 1919, Enver Pasha was the wandering nightmare of western politicians and the unseen terror of global military strategists! In reality, he was just Ali Bey, an exile awaiting opportunity. Looking for something to fight for. Anything... GWS, 2/01 [rev. 4/08] | ||

|

Part 6:

There must be something to fight for, anything... |

|

Opportunity Knocks in Russia After hearing of promising opportunities in the east from other former committee members, Enver attempted to reach Russian territory in May 1919 by aeroplane. Owing to mechanical trouble, he was forced to land near Riga. Enver attempted to return to Germany on land but was arrested at Shavli (Siauliai) by the Lithuanian government on charges of being a spy. He was imprisoned in Kowno (Kaunas) while the Lithuanians contemplated what to do with their famous captive. After four months of captivity, Enver escaped and was able to cross back into Germany where he waited for more favorable traveling conditions. He returned to Berlin, and made surprising contacts with the imprisoned bolshevik emissary Karl Radek in August 1919, who suggested he attempt to bring revolution to the Islamic people of the World. He made up his mind to visit Soviet Russia in order to make this new dream a reality. Traveling by boat was out of the question, since he was wanted by the Entente. Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia were all clients of the Entente and also engaged in sporadic fighting with the Russians. Finally, almost a year later, open war between Poland and Russia provided a narrow window of opportunity. The Red Army's advance to the German frontier in July 1920 permitted him to cross into the Russian zone without hindrance. Two commissars were waiting for him at the Grajewo border crossing on 10 August. Together, they traveled via Grajewo, Vilnius, Minsk, and Smolensk, and Enver finally arrived in Moscow on 16 August 1920. With him was a special briefcase from his friend, General von Seeckt, containing a proposal for a secret military alliance between Soviet Russia and Germany. Enver was the starter of negotiations that ended with the infamous Rapallo Treaty of 1922, which permitted the German general staff to maintain secret military training and weapons installations on Russian soil. Following interviews with Lenin, Trotsky, and Brussilov, Enver was forced to wait for months, ostensibly to await favorable conditions for his agenda. His hosts were distracted by the see-sawing events on the Polish war front at that time, anyway. In September 1920, as the "Miracle of the Vistula" swept the Red army out of Poland, Enver traveled to Baku to be a special guest speaker at the bolshevik "Congress of Eastern Peoples" chaired by Zinoviev. Scarcely versed in the ideology of Marxism, Enver nevertheless proclaimed the importance of unifying the Turanian peoples from the Bosporus to the Gobi. Whether this great task be accomplished under the crescent of Islam or the sickle of communism mattered little to the former war minister. Among the speakers was Enver's old contact in Berlin, Karl Radek. Meanwhile, the Soviets swallowed their stunning defeat on the Polish battlefield by making fresh conquests all across the Caucasus and the far east. Enver was finally dispatched to Batum in April 1921. They kept him there as a virtual prisoner in order to lead a revolutionary army into Turkey should the Nationalist government under Kemal Pasha be destroyed by the Greek offensive then underway. The Greeks were favored to win, as both the Soviets and the Nationalists believed the Greeks were being heavily supported and directed by the Entente. The Turkish victory at Sakarya caused the Soviets to rethink their policy in Turkey. The Entente had long known of the "friendship" between the Soviets and the Nationalists. Kemal's Ankara government was the first to recognize the Soviet government and vice-versa. Preparing to Bring Red Revolution into Turkey What the Entente didn't realize was that both were preparing for war against the other. Kemal didn't trust any of his "friends" in Moscow, especially when he learned of Enver's army stationed on the border. Soviet suggestions that the army was to be transported across the Caspian Sea to fight in Turkestan were dismissed by Kemal, who knew that Enver was far more interested in Turkey than Central Asia. Indeed, Enver had written his uncle Halil in December 1920, telling him that soon, he would march into Anatolia at the head of a vast Moslem force. A few months later, he informed his supporters in Turkey that they should prepare an armed organization that could dominate the situation in Central Anatolia once he began his revolutionary invasion. Halil begged Enver to wait until the Entente had finished their London Conference on the Eastern Question. If the settlement was unsatisfactory to the Turkish people, they might be more willing to overthrow both the Sultan in Constantinople and Kemal in Angora. As it turns out, the defeat of the Greeks was tonic enough for the Turkish people to rally around Kemal's Nationalist government. Kemal had actually written to Enver in November 1920. Kemal had wanted peace with Moscow to secure his eastern frontier, but the continued presence of Enver in the Transcaucasus had done nothing to help the situation. Therefore, Kemal wrote Enver, telling him to foment Moslem uprisings in the Eastern countries--Turkestan, India, Afghanistan, etc. without informing the Soviets of his plans, and to keep in touch with the Nationalist government of his progress. At this time, the Soviets allowed Enver to come and go as he pleased. Therefore, Nationalist Representative Kazim Karabekir went so far as to suggest giving aid to Enver in order to begin a revolution in Azerbaijan and points eastward. Enver was not to be fooled by this scheme, however. He already had an army at his disposal and enjoyed at least superficial confidence from Moscow He remained in Batum, awaiting orders to cross the border and bring revolution to Turkey. Thus, when

the Treaty of Kars was signed between Karabekir and Soviet Ambassador

Ganetski, the former asked the Ambassador why the Soviets had kept Enver

in Batum? Surely, it was an act of war, Karabekir reasoned--this was the

sort of talk that was carried on during the signing of the Peace Treaty

between the Turkish Republic and the Soviets. Karabekir also asked

Ganetski to come clean and tell him whether the Soviets expected the fall

of the Turkish Republic and its imminent replacement by a Soviet system of

government. Ganetski was evasive, and assured Karabekir that Enver was a

freebooter with no serious credentials. The two plenipotentiaries signed

the Treaty of Kars, which ended all border disputes and guaranteed normal

relations between the two states. Turkey was given Kars, Ardahan, and

Artvin, which it claimed at the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918; the

Soviets were allowed to retain Batum, whose claim Turkey

dropped. |

||

|

Part 7: My

mission is to be a savior once more! |

|

Before Enver, "...first Halil and Jemal Pashas

arrived in Moscow [May 1920] with the aim of undertaking propaganda on

behalf of 'Islamic Revolutionary Society' [now known to have been

headquartered in Berlin]," writes Togan. |

||

|

Part 8: The death of Enver Pasha |

|

ENVER PASHA SLAIN BY SOVIET FORCE;

|

||

|

Part 9:

Bringing this tale up-to-date |

|

| Turkish Daily News 5 Aug 1996 ISTANBUL- "A state funeral was held in Istanbul Sunday for Enver Pasha (1881-1922), the mercurial and tempestuous leader of the Young Turks revolution and a member of the triumvirate that ruled the Ottoman Empire during World War I. In military ceremonies, attended by President Suleyman Demirel, ministers, deputies and Turkey's top generals, authorities buried the remains of the Ottoman general and former war minister, returned to Turkey Saturday from Tajikistan, at the H?rriyet-i Ebediye Tepesi, a memorial hill in the Caglayan district. "Enver Pasha, with his faults and merits, is an important symbol of our recent history. We have no doubt that history will reach the proper judgements through evaluating past events," President Suleyman Demirel said, adding that Enver Pasha's separation from his home country and exile had come to an end. State Minister Abdullah Gul said that Enver Pasha was a general who had died along with thousands of others, thus attaining the status of a martyr, while fighting to unite all Muslim and Turkic countries in Asia. "We will build a monument on the spot where Enver Pasha's grave used to be," he said. The hill contains an impressive monument 12 meters high commemorating the 1908 Young Turks revolution that restored the constitution and ended the absolute monarchy in the Ottoman Empire as well as the tombs of many of the leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress, the political group that ruled the Ottoman Empire from 1900-1918. "The funeral began with a religious ceremony at Sisli Mosque, in downtown Istanbul, where thousands of Turks gathered. The flag-draped coffin was then carried through Sisli in a hearse to Memorial Hill where Enver Pasha was buried in a newly built tomb next to Talat Pasha, one of the Ottoman World War I triumvirate. The ceremony was held on the 74th anniversary of his death Enver Pasha entered the Turkish army and was sent to Salonika, where he instigated the Young Turks revolt. He served as military attache in Berlin in 1909, returning to Istanbul to help suppress a counterrevolution. He eventually became leader of the triumvirate, which included Ottoman Prime Minister Talat Pasha and Cemal Pasha, the marine minister, that led the Ottoman Empire to its defeat in World War I on the side of Germany and the losing Axis Powers and to its dismemberment. "After the end of the war, he was court-martialed in 1919 for signing a secret deal with the Germans and sentenced to one-year in exile and deprived of his civil rights. He was also blamed for leading the disastrous Sarikamish winter military campaign in 1914, during which nearly 70,000 Ottoman soldiers froze to death in the cold weather. "After the war, he fled from Istanbul to Germany and eventually to Russia where he sided first with the White Russians and then the Bolsheviks, with whom he finally broke to lead a failed Pan-Turkist movement aimed to unite all Turks under one flag in Central Asia. He was killed in a battle on Aug. 4, 1922, leading a cavalry charge against Bolshevik troops near Dushanbe. The Turkish delegation responsible for bringing back the body of Enver Pasha from Tajikistan have said that they were impressed by the local people's commitment to the Turkish national hero. The residents of the remote mountain village of Obtar in Belcivan, Tajikistan, say that they understand that the Pasha, whom they deem to be a 'martyr' and a 'hero,' is going back to his motherland, but that they feel sad that they are parting from him. They say that it is a consolation that a monument will be built in the place of the grave. The Turkish delegation is also bringing back a letter to Mahpeyker Hanim, Enver Pasha's daughter from a "close friend of her father whom she does not know," living in the village of Obtar. Muzaffer Sah, who took care of the Pasha's grave, is the person who has helped the most to end the Pasha's 74-year long separation from his home country. "Muzaffer Sah's links to Enver Pasha go back to his father, Talip Sah, who took care of financial matters at Enver Pasha's headquarters. After removing the Pasha's dead body so that it would not be desecrated by the Russians, Talip Pasha built a secret grave for him not only on Cegan Hill, but also on the spot where the Pasha's blood had collected in a ditch. Talip Sah considered it a sacred duty for himself and his family to protect the grave of Enver Pasha, whom he called 'my commander' and accompanied until his last breath. Muzaffer Sah, who is leading a very harsh life in Tajikistan which is currently suffering from political and economic crises, wrote in his letter: "We greet the daughter of Enver Pasha. We have taken good care of your father for 75 years. We hope you will help us." Osman Mayatepek, the grandson of the Pasha, could not hold back his tears upon reading the letter. "The Pasha's family will not let such an example of loyalty go unrewarded," he said." Top |

||

|

Part 10:

The son of Enver |

|