MORE NEANDERTAL INSIGHTS:

Table 1 taken

from:

Table 1 taken

from:

KRINGS, DNA sequence

of the mitochondrial

hypervariable region II from

the Neandertal type specimen,

Proc. Natl.

Acad. Sci. USA,

Vol. 96, pp. 5581–5585, May

1999.

This article can be found and accessed for free at

(in html or in PDF):

Figure 1. Illustration of Neandertal Man ,

John Gurche/National Geographic.

A fragment of the original article that Lindahl reviews in the next space (the first mtDNA comparison of a neandertal bone) can be found for free at:

http://mendel.uab.es/biocomputacio/treballs98-99/Villatoro/artcell.htm

Tomas Lindahl, Facts and

Artifacts of Ancient DNA, Cell, Vol. 90, 1–3, July 11, 1997

Excerpts:

“Neandertals, named after

the German valley where these fossils were first discovered, were about 30% larger

than an average modern man and of great muscular strength. They had low

foreheads, protruding brows, and large noses with broad nostrils and were meat

eaters.

The paucity of

the fossil record has not allowed a direct resolution of this important problem,

although recent morphological studies of the nasal cavity of Neandertals favor

the alternative that they represented a distinct and separate species, Homo

neanderthalensis (Schwartz and Tattersall, 1996).

The small

amount of sequence divergence observed in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from

different contemporary human populations, especially in Europe, also indicates

a relatively recent origin of Homo sapiens without significant admixture

of ancient Neandertal sequences… (Torroni, A., Lott, M.T., Cabell, M.F., Chen,

Y.-S., Lavergne, L., and Wallace, D.C. (1994). Am. J. Hum. Genet. 55,

760–776.)”

“Neandertals,

however, seem to have been more similar to modern humans than to apes in having

a low species-wide mtDNA diversity. In the case of humans, the low genetic

diversity seen in both mtDNA and nuclear DNA sequences is likely to be the

result of a rapid population expansion from a population of small size, often assumed

to have been made possible by some cultural

or genetic innovation, such as use of a complex language”.

Fragment taken from:

Krings, A view of Neandertal genetic diversity, Nature

Genetics volume 26 •

october 2000, 144-146

“For many

years, the Neanderthals have been recognized as a distinctive extinct hominid

group that occupied Europe and western Asia. Our ongoing studies indicate that

the Neanderthals differ from modern humans in their skeletal anatomy in more

ways than have been recognized up to now. The purpose of this contribution is

to describe specializations of the Neanderthal internal nasal region that make

them unique not only among hominids but possibly among terrestrial mammals in

general as well. These features lend additional weight to the suggestion that

Neanderthals are specifically distinct from Homo sapiens”.

Abstract:

Schwartz, J. H. and I. Tattersall (1996). “Significance of some

previously unrecognized apomorphies in the nasal region of Homo

neanderthalensis.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93(20): 10852-4.

The complete

article can be accessed for free at (in PDF):

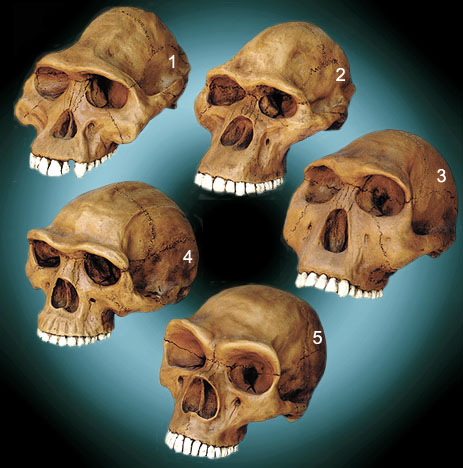

Neandertal and

other possible Nephilim “seeds” (from the artistical reconstructions):

- Australopithecus

afarensis Cranium, 2. Australopithecus africanus Cranium,

- Homo habilis Cranium, 4. Homo erectus Cranium, 5. Neandertal

Cranium

Fragments of the history of this skulls:

Hominid

Series of Five Skulls

“It is from casts, photographs, published diagrams and text

describing these reconstruction's that sculptor Larry Williams has developed

this Hominid Series.

Isaac de la Payrere, from France, discovered stone tools

used by primitive men who, he claimed, lived in the time before Adam. In 1655

his findings and theory were greatly disapproved of and his books publicly

burned by Church authorities.

In 1856, three years before Darwin propounded his theory of

evolution, Neanderthal Man was discovered in Germany's Neander Valley near

Dusseldorf. The skeleton possessed a number of peculiar traits that defined

them as very ancient, including a low, narrow, sloping forehead, heavy eyebrow

ridges, and a deep depression at the root of the nose.

Between 1890 and 1892, Eugene Dubois (member of the Dutch

colonial army) found pieces of "Java Man," (later named Homo

erectus) that everyone agreed was more apelike than the Neanderthal. The

importance of H. erectus was vastly increased from 1927 to 1937 as more

than 40 similar fossils were found in limestone caves at Zhoukoudian, outside

of Beijing. Also found were thousands of stone tools and evidence that H.

erectus used fire. "Beijing Man" was somewhat like the Java erectus.

Homo erectus and Neanderthals were more manlike than apelike (Later

termed Australopithecus). Then, in South Africa, in 1924, Raymond Dart

discovered a apelike. It was followed by the discovery of similar apelike

creatures in Africa, with a brain only slightly bigger than a chimpanzee's. The

nose was flat. The jaw dominated the face and the mouth thrusted forward. But

the teeth were human like and it had a bit of a forehead. Most importantly, it

walked upright! Its spinal cored entered the brain not at the back of the head,

like a gorilla's, but at the bottom of the skull, suggesting bipedalism.

Although that didn't make it human, it allowed it to fall into the broader

category of "hominid."

In all of the fossil finds, however, there was no evidence of

where and when anatomically modern humankind first arose”.

Taken from: http://www.sculpturegallery.com/sculpture/hominid_series_of_five_skulls.html

Compare the skulls presented above

with the next (male and female skulls in artistical reconstructions also):

Human Male and Female Skulls

Taken from:

http://www.sculpturegallery.com/sculpture/human_male_skull.html

http://www.sculpturegallery.com/sculpture/human_female_skull.html

Does Homo neanderthalensis play a role in modern human ancestry? The mandibular evidence. Rak Y, Ginzburg A, Geffen E. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol., 2002 Nov;119(3):199-204:

“The specialized Neanderthal mandibular ramus morphology emerges as yet another element constituting the derived complex of morphologies of the mandible and face that are unique to Neanderthals. These morphologies provide further support for the contention that Neanderthals do not play a role in modern human biological ancestry, either through "regional continuity" or through any other form of anagenetic progression.”

Other fragment showing differences between

humans and neandertals:

“Whatever social contact may have occurred, Hublin and Fred Spoor of University College London conclude that Neandertals and early modern humans did not interbreed. Computerized- tomography scans of nine Neandertal temporal bones, which surround the inner ear, revealed small semicircular canals and a distinctive inner ear shape compared to modern humans. "The differences are comparable to those separating ape species," they said”... “The bone came from a 13- by 16-foot structure made of stalactite and stalagmite fragments. Built by Neandertals, its purpose is unknown.”

MARK BERKOWITZ

http://www.archaeology.org/9609/newsbriefs/neandertals.html

Archaeology Newsbriefs, Vol. 49 # 5

Sept/Oct 1996, Neandertal News

Excerpts of an excellent comment of the article of Schwartz and

Tattersall (1996) previously referred:

Laitman, J.

T., J. S. Reidenberg, Samuel Marquez, and Patrick J. Gannon. (1996). “What the nose knows: new

understandings of Neanderthal upper respiratory tract specializations.” Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA 93(20):

10543-5.

“Who were the

Neanderthals? This brief question has been at the heart of paleoanthropology

since the unearthing of the first Neanderthals almost a century and a half ago.

First found at sites in western Europe, such as the Neander ‘‘thal’’ (now

simply called “tal”) or valley in Germany, Gibraltar, Spy in Belgium, or La

Chapelle-aux-Saints in France, these peculiar remains continue to be an enigma

(1, 2). Were they mere variants of living human populations, somewhat different

so as to indicate a distinct ‘‘race,’’ or were they imbued with

sufficient uniquely derived characters (autapomorphies) so as to warrant their

own species, Homo neanderthalensis?... it is generally agreed that Neanderthals... inhabited a range including much of Europe, western Asia, and the Levant... what happened to them? Although

questions abound, definitive answers are few.

A

confounding problem in the search to understand the Neanderthals, as with

hominid(s)... in general, is that important aspects of their functional

morphology and underlying behaviors have gone largely underinvestigated. This,

in part, is because paleoanthropologists have had to focus upon the scant bony

remains available to them, remains which often do not reflect some major

biological systems. For example, although aspects of the dentition or

postcranial skeleton have been reconstructed meticulously, others, such as

features of the respiratory, digestive, or nervous systems have, more often

than not,

either been ignored or relegated to a relatively minor role in discussions.

The recent

observations by Schwartz and Tattersall (3), in this issue of the Proceedings,

on Neanderthal nasal apomorphies shed new light on the relationship of

Neanderthals to other hominids and add important new data for our understanding

of the functional morphology of a major physiologic system, the upper

respiratory tract. The authors’ primary interest is, of course, how these newly

described features will affect the interpretation of Neanderthal phylogeny. To

be fair, the position of Schwartz and Tattersall on this issue is well known

among anthropologists, with both recognized as ‘‘splitters’’ who see

Neanderthals as comprising a distinct species from either living or archaic Homo

sapiens (1, 4, 5). Their prior views notwithstanding, the evidence they

present is of value in its own right and will henceforth have to be factored

into any discussion of Neanderthal relationships.

The findings by

Schwartz and Tattersall regard specializations of internal nasal morphology.

This aspect of the nose has gone largely unexplored in our fossil ancestors.

This is because fragile internal nasal structures are often not reserved in

fossil hominids and because many aspects of the functional morphology

underlying the mammalian nose and associated paranasal sinuses remain poorly

understood. Although accounts of internal nasal morphology have been cursory, there

have been studies on external nasal dimensions of both extant and fossil

hominids (6–9). Indeed, the large size of Neanderthal external nasal

dimensions, and the significant differences they exhibit from those of extant

humans, has been commented upon and documented for some time (10–12).

Schwartz and

Tattersall now bring to the discussion three internal nasal features which have

been previously unrecognized and which they feel are autapomorphic to

Neanderthals: (i) an ‘‘internal nasal margin,’’ a medially projecting

rim of bone just within the anterior edge of the anterior nasal (piriform)

aperture; (ii)a pronounced medial swelling of the lateral nasal wall;

and (iii) a lack of an ossified roof over the lacrimal groove.

Should the

features observed by Schwartz and Tattersall indeed prove to be true

apomorphies, they would provide strong evidence to support the contention that

Neanderthals are different from extant or fossil Homo sapiens in seminal

ways. But in what ways? And what do distinctions in their nasal region reflect?

While focusing upon questions of Neanderthal systematics, Schwartz and

Tattersall have led us to ponder pivotal questions about how the Neanderthals

may have differed from us in aspects of their respiratory tract and constituent

behaviors.

The acquisition

and processing of oxygen and its byproducts is the primary mission of any

air-breathing vertebrate. Chewing, walking, reproducing, thinking are all fine,

but first one has to breathe. Anthropologists sometimes seem to forget this... Although...

some workers have attempted to

reconstruct the... aspects of our more elusive respiratory behaviors.

This work has focused largely on reconstructing the upper respiratory, or

aerodigestive, tract and has been principally concerned with establishing what

the overall positioning of structures such as the larynx, tongue, and pharynx

may have been like in hominid(s)... Our own studies (13–16) among others

(17–19) have shown that aspects of the external contour of the skull base are

intimately related to the topographic arrangement of aerodigestive tract

structures and can, in turn, serve as a guide to help reconstruct the anatomy

of the region... In essence, we have learned that the

basicranium is the ‘‘roof’’ of the upper respiratory tract and that it can

serve as a blueprint from... the ‘‘house’’ below... By

coupling these data on how upper respiratory tract structures can be

reconstructed with our growing knowledge of the comparative and functional

anatomy of this region in extant mammals (20, 21), we have begun to gain

insight into what the upper respiratory tract may have been like in…

australopithecines (22).

The

configuration of this region in Neanderthals has been the subject of thought

beginning, at least, with the great anatomist Sir Arthur Keith (23). The focus,

however, has usually not been on respiratory requirements and related behaviors

but, rather, on the ‘‘vocal tract’’ component. Although few studies wrestle

with the key issues of upper respiratory change, it seems as if almost everyone

has a word to say on what a Neanderthal’s vocal tract may have been like.

Although the

question of Neanderthal speech capabilities is indeed intriguing, this allure

has seemingly caused many to lose sight of what the area’s main functions were:

respiration and, secondarily, ingestion of food. The region did not evolve for

the sole purpose of vocalization, a fact often overlooked by many.

The

general picture of the Neanderthal upper respiratory tract that has emerged

over the last few decades by those attempting to reconstruct it has been of a

region which differed somewhat from that in living humans. Both our own (15,

16, 24) and other studies (17, 18, 25) have emphasized that some Neanderthals

(such as the ‘‘Classic’’ western European specimens) would have exhibited a

larynx slightly higher in the neck than that of modern humans, with these

Neanderthals having a more limited oropharyngeal segment with a greater portion

of the tongue occupying the oral cavity. When one factors in their large

external nose and sizable paranasal sinuses, the overall Neanderthal anatomy

suggests a group that relied more heavily upon the nasal rather than the oral

route for respiration then do living humans. These specializations were very

possibly due to respiratory-related adaptations to their environment. A

by-product of this respiratory-driven anatomical configuration would be that

Neanderthals could not have produced the same array of sounds that living

humans can (16, 17, 26). They were not apish mutes; they were just not

identical to us.

Although the

above scenario has been accepted by many, it is unpalatable to some. This group,

often called ‘‘lumpers,’’ is primarily comprised of those who view

Neanderthals as falling within the range of variation represented by diverse

modern human populations (27). Given their predilection, it becomes a priori

impossible for them to view Neanderthals as ever being sufficiently

different so as to exhibit highly derived respiratory anatomy or specialized

respiratory or vocal behaviors. If they are us, then they cannot be

fundamentally different. Observations on the difference between Neanderthals

and extant populations are routinely dismissed as being within the range of ‘‘human’’

variation.

Given

the above, Schwartz and Tattersall’s nasal findings harbor important

implications. The three traits they describe clearly suggest a morphology that

is different from ours and appears designed to subserve specialized functions.

The large internal nasal margin they describe, their major observation, may

serve to expand the internal surface area, thus allowing for an increase in

ciliated mucosal covering. The placement of this margin, at the very entrance

of the cavity, also suggests a location ideally suited to be the initial

vehicle to confront

inspired air or

the last opportunity to interact with expired air.

In some ways,

this medial projection is reminiscent of Waldeyer’s Ring, the

mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues (lingual, palatine, nasopharyngeal tonsils)

that surround internal respiratory and digestive portals. Could Neanderthals

have had a similar ‘‘donut-shaped’’ filter system at the entrance to the

nasal cavity?

Both the internal nasal

margin and Schwartz and Tattersall’s second feature, a swelling of the lateral

nasal cavity, may be related to expansions of the paranasal sinus system.

Indeed, sinuses have long been known to be extensive in Neanderthals (28),

and amplifications of these would thus be logical. Al-though the exact

function(s) of mammalian paranasal sinuses remains unclear, and have indeed

become the focus of much recent study (29–31), it is likely that in

Neanderthals they played at least some part in an air-exchange process, perhaps

in warming and humidifying cold and dry air. The relationships/ functions of an

unossified roof over the lacrimal groove, Schwartz and Tattersall’s third

observation, is less clear. The absence of a rigid roof, however, would clearly

permit more expandability for components of the nasolacrimal duct system

(which, in humans, contains a venous plexus forming erectile tissues and can,

when engorged, obstruct the duct).

Absence of a bony roof

would also allow for a more direct communication of nasolacrimal duct contents

with the environment of the nasal cavity proper.

As an initial

foray into this region in Neanderthals, many questions have yet to be

addressed. An important issue, not covered by Schwartz and Tattersall, regards

the extent (or even presence) of these proposed apomorphies in Neanderthals

from different geographic areas. For example, because the Neanderthals focused

on by the authors are from western Europe, it will be important to determine the

extent of these characters in Neanderthals from other areas, such as eastern

Europe or the Levant. If regional variations are found, could there be any

relationship to climatic differences? Similarly, further work is needed to

determine...

whether, as the authors suggest, the presence of a ‘‘poorly developed’’

medial projection in the Steinheim cranium (a specimen

generally

thought not to be a Neanderthal) is evidence for an entire Neanderthal clade.

The

apomorphies described by Schwartz and Tattersall offer strong evidence that the

internal morphology of the nasal moiety of the Neanderthal upper respiratory

tract may be as distinctive as that previously reconstructed for the more

caudal laryngo-pharyngeal component. Taken together, these specialized

features of

different upper respiratory tract compartments allow greater insight into an

apparently more global pattern to Neanderthal upper respiratory

specializations. Although these specializations may not by themselves validate

Schwartz and

Tattersall’s preference for Neanderthal taxonomic distinctiveness, they

certainly lend strong support to those who see Neanderthals as considerably

different from living Homo sapiens. Indeed, further clues to

understanding just how different Neanderthals are from living humans may be

as plain as the

anatomy inside the noses on their faces.”

References:

1. Tattersall,

I. (1995) The Last Neanderthal: The Rise, Success, and

Mysterious

Extinction of Our Closest Human Relatives (Macmillan,

New York).

2. Stringer, C.

& Gamble, C. (1993) In Search of the Neanderthals:

Solving the

Puzzle of Human Origins. (Thames & Hudson, London).

3. Schwartz, J.

H. & Tattersall, I. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA

93, 10852–10854.

4. Schwartz, J.

H. (1993) What the Bones Tell Us (Henry Holt, New

York).

5. Tattersall,

I. (1986) J. Hum. Evol. 15, 165–175.

6. Thomson, A.

& Buxton, L. H. D. (1923) J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 53,

92–133.

7. Wolpoff, M.

H. (1968) Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 29, 405–423.

8. Glanville,

E. V. (1969) Am J. Phys. Anthropol. 30, 29–38.

9. Franciscus,

R. G. & Trinkaus, E. (1988) Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.

75, 517–527.

10. Coon, C. S.

(1962) The Origin of Races (Knopf, New York).

11. Franciscus,

R. G. & Trinkaus, E. (1988) Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.

75, 208.

12. Trinkaus,

E. & Shipman, P. (1993) The Neandertals: Changing the

Image of

Mankind (Knopf, New York).

13. Laitman, J.

T., Heimbuch, R. C. & Crelin, E. S. (1978) Am. J.

Anat. 152, 467–483.

14. Reidenberg,

J. S. & Laitman, J. T. (1991) Anat. Rec. 230, 557–569.

15. Laitman, J.

T., Reidenberg, J. S. & Gannon, P. J. (1992) in

Language

Origin: A Multidisciplinary Approach, eds. Wind, J.,

Chiarelli, B.,

Bichakjian, B. & Nocentini, A. (Kluwer, Dordrecht,

The

Netherlands), pp. 385–397.

16. Laitman, J.

T., Heimbuch, R. C. & Crelin, E. S. (1979) Am. J.

Phys.

Anthropol. 51, 15–34.

17. Lieberman,

P. & Crelin, E. S. (1971) Ling. Inq. 2, 203–222.

18. Grosmangin,

C. (1979) Mem. Lab. Anat. Fac. Med. Paris 40,

1–241.

19. Budil, I.

(1994) Hum. Evol. 9, 35–52.

20. Laitman, J.

T. & Reidenberg, J. S. (1993) Dysphagia 8, 318–325.

21. Harrison,

D. F. N. (1995) The Anatomy and Physiology of the

Mammalian

Larynx (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, U.K.).

22. Laitman, J.

T. & Heimbuch, R. C. (1982) Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.

59, 323–344.

23. Negus, V.

E. (1949) The Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of

the Larynx (Grune &

Stratton, New York).

24. Laitman, J.

T., Reidenberg, J. S., Friedland, D. R., Reidenberg,

B. E. &

Gannon, P. J. (1993) Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. Suppl. 16,

129.

25. Crelin, E.

S. (1987) The Human Vocal Tract: Anatomy, Function,

Development and

Evolution (Vantage, New York).

26. Lieberman,

P., Laitman, J. T., Reidenberg, J. S. & Gannon, P. J.

(1992) J.

Hum. Evol. 23, 447–467.

27. Wolpoff, M.

H. (1996) Human Evolution (McGraw–Hill, New

York).

28. Tillier, A.

M. (1975) The`se de 3 e cycle (Univ. of Paris, Paris).

29. Scharf, K.,

Lawson, W., Shapiro, J. & Gannon, P. J. (1994)

Laryngoscope 105, 1–5.

30. Koppe, T.,

Rohrer-Ertl, O., Hahn, D., Reike, R. & Nagai, H.

(1996) Okajimas

Folia Anat. Jpn. 72, 297–306.

31. Marquez,

S., Gannon, P. J., Reidenberg, J. S. & Laitman, J. T.

(1996) Assoc.

Res. Otolaryngol. Abstr. 19, 158.

This original

comment can be found only in PDF for free at:

APPENDIX:

Some

mitochondrial DNA fragments from neandertals:

In the next address can be freely found this and any other

sequence from living beings:

(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Database/index.html)

AF011222

Krings,M., Stone,A., Schmitz,R.W., Krainitzki,H., Stoneking,M. and Paabo,S., Neandertal DNA sequences and the origin of modern humans, Cell 90 (1), 19-30 (1997)

Homo sapiens neanderthalensis

mitochondrial D-loop hypervariable region 1

1 gttctttcat gggggagcag atttgggtac cacccaagta ttgactcacc catcagcaac 61 cgctatgtat ctcgtacatt actgttagtt accatgaata ttgtacagta ccataattac 121 ttgactacct gcagtacata aaaacctaat ccacatcaaa cccccccccc catgcttaca 181 agcaagcaca gcaatcaacc ttcaactgtc atacatcaac tacaactcca aagacgccct 241 tacacccact aggatatcaa caaacctacc cacccttgac agtacatagc acataaagtc 301 atttaccgta catagcacat tacagtcaaa tcccttctcg cccccatgga tgacccccct361 cagatagggg tcccttgat

AF142095

Krings,M., Geisert,H., Schmitz,R.W., Krainitzki,H. and Paabo,S., DNA sequence of the mitochondrial hypervariable region II from the neandertal type specimen, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (10), 5581-5585 (1999).

Homo sapiens neanderthalensis mitochondrial control region, hypervariable region II. 1 ttttcgtctg gggggtgtgc acgcgatagc attgcgagac gctggagccg gagcacccta 61 tgtcgcagta tctgtctttg attcctgccc cattccatta tttatcgcac ctacgttcaa 121 tattacaggc gagcatactt actaaagtgt gttaattaat taatgcttgt aggacataat 181 aataacgact aaatgtctgc acagctgctt tccacacaga catcataaca aaaaatttcc 241 accaaacccc ctttcctccc ccgcttctgg ccacagcact taaacacatc tctgccaaac301 cccaaaaaca aagaacccta acaccagcct aaccagactt caaat

AF254446

Ovchinnikov,I.V., Gotherstrom,A., Romanova,G.P., Kharitonov,V.M., Liden,K. and Goodwin,W., Molecular analysis of Neanderthal DNA from the northern Caucasus, Nature 404 (6777), 490-493 (2000).

Homo sapiens neanderthalensis mitochondrial D-loop, hypervariable region I. 1 ccaagtattg actcacccat caacaaccgc catgtatttc gtacattact gccagccacc 61 atgaatattg tacagtacca taattacttg actacctgta atacataaaa acctaatcca 121 catcaacccc ccccccccat gcttacaagc aagcacagca atcaaccttc aactgtcata 181 catcaactac aactccaaag acacccttac acccactagg atatcaacaa acctacccac 241 ccttgacagt acatagcaca taaagtcatt taccgtacat agcacattat agtcaaatcc301 cttctcgccc ccatggatga cccccctcag ataggggtcc cttga

AF282971

Krings,M., Capelli,C., Tschentscher,F., Geisert,H., Meyer,S., von Haeseler,A., Grossschmidt,K., Possnert,G., Paunovic,M. and Paabo,S., A view of neandertal genetic diversity, Nat. Genet. 26 (2), 144-146 (2000).

Homo sapiens neanderthalensis mitochondrial hypervariable region I sequence. 1 gttctttcat gggggagcag atttgggtac cacccaagta ttgactcacc catcagcaac 61 cgctatgtat ttcgtacatt actgccagcc accatgaata ttgtacagta ccataattac 121 ttgactacct gcagtacata aaaacctaat ccacatcaac cccccccccc catgcttaca 181 agcaagcaca gcaatcaacc ttcaactgtc atacatcaac tacaactcca aagacgccct 241 tacacccact aggatatcaa caaacctacc cacccttgac agtacatagc acataaagtc 301 atttaccgta catagcacat tacagtcaaa tcccttctcg cccccatgga tgacccc AF282972

Krings,M., Capelli,C., Tschentscher,F., Geisert,H., Meyer,S., von Haeseler,A., Grossschmidt,K., Possnert,G., Paunovic,M. and Paabo,S., A view of neandertal genetic diversity, Nat. Genet. 26 (2), 144-146 (2000).

Homo sapiens neanderthalensis mitochondrial hypervariable region II sequence. 1 ttttcgtctg gggggtgtgc acgcgatagc attgcgagac gctggagccg gagcacccta 61 tgtcgcagta tctgtctttg attcctgccc cattccatta tttatcgcac ctacgttcaa 121 tattacaggc gagcatactt actgaagtgt gttaattaat taatgcttgt aggacataat 181 aataacgact aaatgtctgc acagctgctt tccacacaga catcataaca aaaaatttcc

241 accaaacctc cccctccccc gcttctggcc acagcactta aatacatc

AY149291

Schmitz,R.W., Serre,D., Bonani,G., Feine,S., Hillgruber,F., Krainitzki,H., Paabo,S. and Smith,F.H., The Neandertal type site revisited: interdisciplinary investigations of skeletal remains from the Neander Valley, Germany, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (20), 13342-13347 (2002).

Homo sapiens neanderthalsensis mitochondrial D-loop hypervariable region I, partial sequence. 1 gttctttcat gggggagcag atttgggtac cacccaagta ttgactcacc catcagcaac 61 cgctatgtat ttcgtacatt actgccagcc accatgaata ttgtacagta ccataattac 121 ttgactacct gcagtacata aaaacctaat ccacatcaac cccccccccc catgcttaca 181 agcaagcaca gcaatcaacc ttcaactgtc atacatcaac tacaactcca aagacaccct

241 tacacccact aggatatcaa caaacctacc cacccttgac agtacatagc acataaagtc 301 atttaccgta catagcacat tacagtcaaa tcccttctcg cccccatgga tgacccc

Comparing Neanderthal sequences with human's (with "BLAST"), and also human - human comparisons:

http://www.oocities.org/fdocch/compare.htm

Go to the first part of this review:

http://www.oocities.org/fdocch/new.htm

More Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA Research:

http://www.oocities.org/fdocch/neil.htm

Clear proofs of Neandertal Cannibalism: Cave finds revive Neandertal cannibalism (Evidence found at cave site in southeastern France):

Science News, Oct 2, 1999, B. Bower

Neanderthal Eats Neanderthal:

Neandertals' diet put meat in their bones:

Science News June 17, 2000, B. Bower

Neanderthals Did Their Own Killing:

By Trina Wood, Discovery.com News, June 13, 2000

White, Tim D. (August, 2001). “Once Were Cannibals"Scientific American 58-65.

An excerpt in Word Document of this thoughtful article

Some other references of the neandertal cannibalism:

Defleur, A., T. White, et al. (1999). "Neanderthal cannibalism

at Moula-Guercy, Ardeche, France." Science 286(5437): 128-31.

Richards, M. P., P. B. Pettitt, et al. (2000). “Neanderthal diet

at Vindija and Neanderthal predation: the evidence from stable isotopes.” Proc

Natl Acad Sci U S A 97(13): 7663-6.

White, T. D. (1992). “Prehistoric Cannibalism at Mancos 5MTUMR-2346."Princeton University Press

Marlar, R. A., et al (September 7, 2000). “Biochemical Evidence of Cannibalism at a Prehistoric Puebloan Site in Southwestern Colorado."Nature (407):74-78.

http://www.webster.sk.ca/GREENWICH/chewchip.htm CHEWED OR CHIPPED? Who Made the Neanderthal Flute? HUMANS OR CARNIVORES?

By Bob Fink

Updated Nov, 2ooo

New attempts made by a Scientific foolishness: the "reproduction" of two individuals of the same sex: "Theoretically, these new techniques could eventually also allow

same-sex couples to reproduce", according to the article of Peter O'Connor

... this example and any other homosexually oriented program, are wrong, according to God's Word:

New Experimental Fertility Technique

Tasters of the Word (YouTube), videos recientes: "Astronomía y Nacimiento de Jesucristo: Once de Septiembre Ańo Tres A.C.", "Estudio sobre Sanidades" (en 20 episodios), "Jesus Christ, Son or God?" and "We've the Power to Heal":

Tasters of the Word (the blog, with: "Astronomy and the Birth of Jesus Christ"):