Wanted, A Wife by Ellen Thorneycroft Fowler - The Woman At Home Volume V, 1896

fell upon a day that the worthy governors of the Grammar School at Pendlebury were called upon to fulfil the onerous duty of selecting and electing a new Head-master. By the outlay of a few paltry hundreds a year they expected to retain the services of as much intellect, culture, knowledge, and experience as could be packed into some six feet of human flesh; and they further demanded that this six feet of packing-case should be endowed with the manners of a marquis and the cricketing prowess of a professional. To the inhabitants of another planet it might appear that the governors of Pendlebury School expected a good deal for their money; but anybody who knows anything about this "best of all possible worlds" will readily perceive that a sum whereat a prize-fighter or a ballet-dancer would be justified in turning up their respective noses is generous - nay, extravagant - compensation for the services of a mere wrangler or double-first. So Wisdom was justified of those of her children who had a place upon the governing body of Pendlebury School.

fell upon a day that the worthy governors of the Grammar School at Pendlebury were called upon to fulfil the onerous duty of selecting and electing a new Head-master. By the outlay of a few paltry hundreds a year they expected to retain the services of as much intellect, culture, knowledge, and experience as could be packed into some six feet of human flesh; and they further demanded that this six feet of packing-case should be endowed with the manners of a marquis and the cricketing prowess of a professional. To the inhabitants of another planet it might appear that the governors of Pendlebury School expected a good deal for their money; but anybody who knows anything about this "best of all possible worlds" will readily perceive that a sum whereat a prize-fighter or a ballet-dancer would be justified in turning up their respective noses is generous - nay, extravagant - compensation for the services of a mere wrangler or double-first. So Wisdom was justified of those of her children who had a place upon the governing body of Pendlebury School.

And the expectations of the governors were fulfilled. Numberless scholars and gentlemen applied for the desirable post; and the lot finally fell upon John Mortimer, Esq., M.A., whose testimonials read like a Liebig's Extract of the "Lives of the Saints," flavoured with the essence of Bacon's "Advancement of Learning." There seemed nothing that John Mortimer could not do - still less that John Mortimer did not know; in addition to which unparalleled virtue and knowledge he possessed a handsome appearance and a charming manner, and stood six feet one in his stockings.

But even this rose among schoolmasters was not without the inevitable thorn; and in this case the inevitable thorn took the form of bachelorhood on the part of John Mortimer, Esq., M.A. Now, the governors of Pendlebury School were a kind, fatherly set of old men who held that it was indispensable that there should be someone at the school who could be (as they said) a mother to the boys; and for all his strength and learning there was nothing in the slightest degree motherly about Jack Mortimer. The most vivid imagination could hardly succeed in regarding as a mother a big, black-bearded young man of two-and-thirty, who was a first-class classic and a first-rate cricketer; and schoolboys are, not as a rule, remarkable for the vividness of their imaginations; but on this account it was all the more necessary that Jack Mortimer should take to himself a wife, who could be to his scholars a sign and a symbol of the loving-kindness reserved for them by their respective three hundred mothers at home. The governors therefore officially informed John Mortimer, Esq., M.A., that they had great pleasure in appointing him Headmaster of Pendlebury School on one condition - viz., that he could undertake to become a married man within twelve months of his election.

Jack Mortimer was a man who didn't trouble his head about women at all. He regarded a wife very much as he regarded a sideboard - viz., as a useful piece of furniture which no middle-aged householder should be without, but which would prove a ridiculously troublesome and cumbrous trinket for a young man to drag all over the country with him. He was naturally at first somewhat staggered by the condition of his election; but he reflected that after all, in this overcrowded country of ours, appointments are increasingly hard to find and wives increasingly easy; so, after due deliberation, he accepted the Headmastership, with a Micawberish hope that something would turn up ere the year of probation was over. The governors were kind enough to say that, failing a wife, they would graciously accept a sister in her stead; but Jack had never had a sister in his life, and realised the fact that - though a man is never too old to take a wife - having a sister, like playing on the violin, is a thing which one must begin in early youth or not at all.

Jack Mortimer was a man who didn't trouble his head about women at all. He regarded a wife very much as he regarded a sideboard - viz., as a useful piece of furniture which no middle-aged householder should be without, but which would prove a ridiculously troublesome and cumbrous trinket for a young man to drag all over the country with him. He was naturally at first somewhat staggered by the condition of his election; but he reflected that after all, in this overcrowded country of ours, appointments are increasingly hard to find and wives increasingly easy; so, after due deliberation, he accepted the Headmastership, with a Micawberish hope that something would turn up ere the year of probation was over. The governors were kind enough to say that, failing a wife, they would graciously accept a sister in her stead; but Jack had never had a sister in his life, and realised the fact that - though a man is never too old to take a wife - having a sister, like playing on the violin, is a thing which one must begin in early youth or not at all.

At first he was very happy in his new position. He had a charming house, he liked his work, he was full of ambition as to the reforms he would effect in the school committed to his charge; and for a time he quite forgot the wife difficulty. But the governors and their better halves did not forget it; they regarded the vacant post as the prerogative of one of their own unmarried progeny, and they straightway commenced a lively competition as to which of their domestic goddesses should receive the apple which this tutorial Paris was about to award. This plan of campaign consisted of a round of dinner-parties, whereat Jack in turn took in to dinner the various candidates for his consortship. Sometimes this arrangement amused the Headmaster; but at others he longed to fall at his hostess's feet, and implore her that for once he might take an ineligible female in to dinner, and imbibe his nourishment in peace. But this would not have been business; and the wives and mothers of Pendlebury were nothing if not women of business.

Mortimer's first dinner-party - his début, so to speak - was under the hospitable roof of Mr and Mrs Grover, and of course their daughter Emmeline fell to his lot as a partner at meat. Jack was a poor hand at talking to girls, even when he was not conscious that they were hunting him down, and he now felt his lips were doubly sealed. But not so Emmeline. She began the bombardment without wasting a moment.

"O" (Emmeline's remarks - like the Irish aristocracy - were never without the prefix O), "O, Mr Mortimer! how fond you must be of all those dear little boys of yours! Do tell me something about them, please, for I am so fond of boys."

Now, Emmeline Grover was a nice-looking girl with a kind heart and an amiable temper, but she had failed to learn two of the principal rules of the game of dinner conversation: firstly, that until the entrées have passed from the region of hope to the limbo of memory, and the edge is thereby taken off the gentleman's appetite, the lady should talk to him without even expecting him to listen; and secondly, that if the gentleman is over forty years of age he likes the lady to agree with him; but if he is under forty he prefers her to differ, as he is still young enough to believe that his arguments will have power to convert her. But these things were as yet hid from Emmeline, and so, conversationally, she went wrong from the beginning.

"Fond of boys, are you, Miss Grover?" replied Jack, perversely; "I wish I were!"

"Fond of boys, are you, Miss Grover?" replied Jack, perversely; "I wish I were!"

"O, aren't you, Mr Mortimer - aren't you really? How shocking of you!"

Jack spooned up his soup in silence, not feeling called upon to reply; but Emmeline was not to be daunted.

"I read your testimonials with such interest, Mr Mortimer, and they said what a wonderful man you are with boys, and how you are 'one with them in their games as in their studies.' Those were the exact words. I learned them by heart: they seemed to me so beautiful and so expressive of what is really needed in the proper training of boys."

Jack laughed. "Good gracious, Miss Grover, you donít mean to say you are taken in by testimonials! They are the greatest rot in the world; and of course the more people want to get rid of a man, the better the testimonials they write for him."

"O, Mr Mortimer, how naughty of you to say a thing like that! Surely, surely, it cannot be true. It would destroy all my faith in human nature if I believed it, and it is so sad to lose one's faith in human nature, don't you think?"

Jack wished that Miss Grover's knowledge of human nature equalled her faith therein; but as he did not feel called upon to re-pedestal that young lady's tottering idols, he remained dull and uninteresting for the remainder of the meal; and though Emmeline bravely continued to gush over boys in general, and to treat Jack as if he were an enthusiastic Sunday school teacher, her efforts only succeeded in making him less communicative than usual.

The next aspirant for Jack's vacant half-throne was Sophy Slater, who, of course, fell to his lot at the Slaters' dinner-party. Sophy was one of those useful little women who seem to be made of horsehair - hard and prickly, but warranted to stand any amount of wear and tear. She talked very sensibly to Jack about the school and everything that appertained to it, and gave him most sound advice on many matters.

"The first thing you ought to do is to build a sanatorium," she remarked.

"Do you think so?"

"Of course I do. How should you manage if an epidemic broke out among the boarders?"

"I'm sure I don't know," answered the Headmaster, feebly.

"You will have to build a sanatorium - that is the only thing to do - and you ought to lose no time in setting about it. Be sure you have it at least a hundred and fifty yards away from the other school-buildings, or it will be worse than useless. That is the great disadvantage of a school where boarders and day-scholars are mixed: the day-boys are sure to bring childish and infectious complaints from their various homes, and the boarders are equally sure to assimilate and disseminate the same."

Jack felt as if he were listening to a medical lecture, and ought to be taking copious notes instead of eating and drinking; and he asked humbly:

"How, then, should you advise me to go about it, Miss Slater?"

"I should advise you to call a meeting of the governing body to discuss the matter; and after they have formulated a scheme, that scheme should be submitted to the Town Council. You will have no difficulty about funds, I imagine, as many of the school governors and Town Councillors have boys at the school, and so in their own interests would be glad to insure immunity from epidemic disease there; for which reason the parents of boarders would probably liberally subscribe also."

"Yes, yes, of course."

"You will not want a very large sum of money, for you must not go in for anything extravagant or ornamental; just a plain, square, red-brick building, with plenty of windows for ventilating purposes, will be all you need."

Jack shuddered as he thought of the beautiful school-building, of which he was already so proud, being supplemented by a staring, red-brick sanatorium; but he wisely held his peace.

As he sat smoking in his study late that night, he meditated upon what an helpmeet for a schoolmaster Sophy Slater would prove. Her common sense and efficiency knew no bounds; but as for making love to her...! Jack remembered two old horsehair sofa-cushions in the nursery at home, which he pretended were a little brother and sister, named respectively Blackie and Week. From his third till his sixth year he loved them with a devoted though unrequited affection, and felt deeply their harsh response to his fond embraces. It now struck him that making love to Sophy Slater would be quite as uphill work as performing the part of a loving brother to Week and Blackie; and he decided that he could not begin to play that long and dreary game over again.

As he sat smoking in his study late that night, he meditated upon what an helpmeet for a schoolmaster Sophy Slater would prove. Her common sense and efficiency knew no bounds; but as for making love to her...! Jack remembered two old horsehair sofa-cushions in the nursery at home, which he pretended were a little brother and sister, named respectively Blackie and Week. From his third till his sixth year he loved them with a devoted though unrequited affection, and felt deeply their harsh response to his fond embraces. It now struck him that making love to Sophy Slater would be quite as uphill work as performing the part of a loving brother to Week and Blackie; and he decided that he could not begin to play that long and dreary game over again.

Time would fail to tell of all the various fair claimants to Jack Mortimer's hand. Some of the maidens of Pendlebury sought to attract the Headmaster by putting on Minerva and all her wisdom; while others affected for his subjugation an infantine innocence and ignorance, for which their mothers would have slapped them had they been under five instead of over five-and-twenty. Over one particular damsel - Julia March by name - the Headmaster very nearly lost his head, and thereby secured his mastership; but he caught a side-light one day of the handsome Julia's temper - the light was lurid, and the Headmaster regained his head. At another time he felt he really could have fancied pretty Laura Gregson, if only she had not been a performer on the violin; but Jack belonged to that not unnumerous class of men who hate the women who (as he expressed it) "make noises" - that is to say, who are proficient in either vocal or instrumental music. A woman who played on the piano was an evil thing in Jack's eyes; and his horror of any other instrument was not less in its intensity. But he had his excuses: once he possessed a grandmother who played "The Battle of Prague" on the piano every evening; and though he was but a child at the time, he had neither forgotten nor forgiven her.

Nevertheless, though Mortimer was slow to woo he was quick to work, and the school prospered greatly under his management. Moreover, he followed in his predecessor's footsteps, and gave literature classes to the young ladies of Pendlebury on Wednesday afternoons, which were a great success. Surely never teacher had a more attentive audience! They listened with breathless interest to every syllable which fell from the lecturer's lips; and they wrote sweet little scented essays, which Jack duly returned to them embellished with corrections and marginal notes in red ink. These rosy comments of Jack's were regarded by his hearers as almost inspired, and were by them quoted and re-quoted till they became as household words.

All this was very pleasant to Jack Mortimer until Violet Majendie joined the literature class; then a change came o'er the spirit of his dreams, for a ghastly suspicion dawned upon his mind that this cleverest of his pupils was laughing at him. Jack was by no means destitute of a sense of humour, and the terms of his election had tickled him a good deal at first, but as nobody else in Pendlebury seemed to see anything grotesque in it - and as jokes, like dinners, are all the nicer when they are not at one's own expense - Jack soon ceased to regard his position as being at all unusual or absurd. But when Miss Majendie came home to Pendlebury after an absence of some months, during which period the new Headmaster had come and seen and conquered the Grammar School, a disquieting idea crept into Jack's head that Violet had a keener sense of humour than an all-wise Providence, as a rule, allots to women, and that this keen sense whetted itself at his august expense. It was not that Miss Majendie was rude to him - she was far too well-mannered for that; but she had raised audacity to the level of a fine art, and could say the most impertinent things in the least impertinent manner. For instance, once when they were studying Tennyson's "Oenone," she asked him before the whole class, apparently apropos of nothing:

All this was very pleasant to Jack Mortimer until Violet Majendie joined the literature class; then a change came o'er the spirit of his dreams, for a ghastly suspicion dawned upon his mind that this cleverest of his pupils was laughing at him. Jack was by no means destitute of a sense of humour, and the terms of his election had tickled him a good deal at first, but as nobody else in Pendlebury seemed to see anything grotesque in it - and as jokes, like dinners, are all the nicer when they are not at one's own expense - Jack soon ceased to regard his position as being at all unusual or absurd. But when Miss Majendie came home to Pendlebury after an absence of some months, during which period the new Headmaster had come and seen and conquered the Grammar School, a disquieting idea crept into Jack's head that Violet had a keener sense of humour than an all-wise Providence, as a rule, allots to women, and that this keen sense whetted itself at his august expense. It was not that Miss Majendie was rude to him - she was far too well-mannered for that; but she had raised audacity to the level of a fine art, and could say the most impertinent things in the least impertinent manner. For instance, once when they were studying Tennyson's "Oenone," she asked him before the whole class, apparently apropos of nothing:

"Whom should you have given the apple to, if you had been Paris, Mr Mortimer?"

Jack curtly replied:

"I am here to answer pertinent questions, Miss Majendie, not those which are the reverse."

But though he knew he had scored this time, he nevertheless felt himself growing scarlet to the roots of his black hair, and was inwardly furious with the cause of this unwilling turn at rouge et noir on his part. Violet looked so sweetly unconscious of any rudeness on either her side or his that he could not feel quite sure if the girl had intended to make fun of him after all, or if her question was merely stupid; but stupidity was not a besetment of Miss Majendie's, and Jack could not help wishing that she had been a boy, so that he might have given himself the benefit of the doubt, and soundly caned her for her impudence.

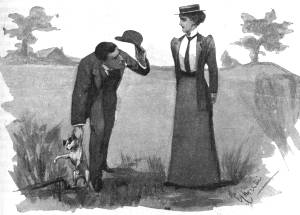

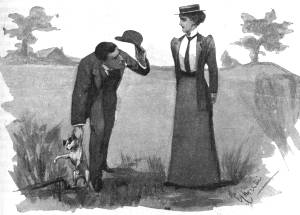

But one half-holiday it came to pass that an avenging fate delivered Jack's enemy into his hands. He was walking in Melton Woods (the favourite resort of the inhabitants of Pendlebury), when he came upon Violet Majendie vainly endeavouring to deliver her pet dog from a trap into which the poor brute had unwarily stepped.

"Allow me, Miss Majendie," said the Headmaster, grimly, raising his hat, but not attempting to shake hands; and after a great deal of trouble he succeeded in releasing the prisoner and drawing upon himself a shower of grateful speeches from the prisoner's mistress. But Jack was not to be beguiled out of his ill-humour so easily, as he was still smarting under a remark of Miss Majendie's, which had been repeated to him by the never-failing "kind friend" whose duty and delight it is to repeat such unflattering comments. So in reply to Violet's profuse thanks he merely said:

"Allow me, Miss Majendie," said the Headmaster, grimly, raising his hat, but not attempting to shake hands; and after a great deal of trouble he succeeded in releasing the prisoner and drawing upon himself a shower of grateful speeches from the prisoner's mistress. But Jack was not to be beguiled out of his ill-humour so easily, as he was still smarting under a remark of Miss Majendie's, which had been repeated to him by the never-failing "kind friend" whose duty and delight it is to repeat such unflattering comments. So in reply to Violet's profuse thanks he merely said:

"You are unnecessarily grateful for so slight a service, Miss Majendie. I could not let a dog remain helpless in a trap, whoever it belonged to, so I have in no wise earned your special gratitude. But in return perhaps you would not mind answering a straightforward question. Did you, or did you not, say that no one but a buffoon would accept an appointment on the terms that I have done?"

Violet looked up at the offended Headmaster with an ingenuous smile.

"I don't remember saying so, Mr Mortimer, but I have always thought it."

Jack grew pale with anger and mortification, and wished more devoutly than ever that this impertinent girl had been a boy, so that he might have meted out to her the measure which she so richly deserved.

"Thank you," he said, shortly.

Violet, however, was not going to let so entertaining a subject drop.

"But, Mr Mortimer," she suggested, in a coaxing voice, "surely you also can see how killingly funny it is. It is very sad for you to be minus a wife, but it would be far worse if you were minus a sense of humour. I thought you had done it for a joke from the first."

Jack felt slightly mollified, for it is distinctly more comfortable to be treated as a spectator of a farce than as a performer therein.

"But," continued Violet, bubbling over with laughter, "you don't go about the thing in the right way. You ought first to set up an age-disqualification, and say that no one over five-and-twenty need apply. That would double the number of candidates at once."

"You are very hard on your own sex."

"Not at all, but I know their little ways. I want our vicar to announce that he is going to preach a sermon to women under five-and-twenty only. The church would be simply crowded, and the offertory, consequently, enormous, as there isn't a woman within a radius of twenty miles who wouldn't make a point of attending that service."

"I am glad to learn that you favour the Church as well as the world with the benefit of your advice, Miss Majendie."

"O! I am not at all stingy with it, and you haven't had your full share yet. Another suggestion I wish to make is that you should insist on all your candidates sending in written applications supported by testimonials. I don't mind telling you that I'd write an excellent testimonial for Sophy Slater."

"Miss Slater is a most admirable young lady," said Jack, stiffly.

"Of course she is. Do you think she would get a testimonial from me if she wasn't? Then, again, Emmeline Grover is a treasure. You couldn't go far wrong with either Sophy or Emmeline."

"Indeed. These young ladies are fortunate in having secured your good opinion," remarked Mortimer, satirically.

But it was beyond the power of scholastic sarcasm to abash Violet, so she calmly continued:

"If Emmeline has a fault, she is almost too adaptive. I remember once, when she wanted to make herself specially agreeable to Colonel Delaware, a great racing man, she told him that she 'adored jockeys; they were always such big fine men.' I suppose she mixed them up in her own mind with guardsmen, but you should just have seen the Colonel's face of utter bewilderment!"

"I do not think it is very kind of you to laugh at people behind their backs," said Jack, in his most headmasterly manner.

"Still, they don't seem to care for it much when I do it before their faces, do they?" replied Violet, looking up at him like a puzzled child.

Jack grew rather red, but, having no answer ready, took refuge in silence.

"Look here, I really don't want to be too rough on you," continued his tormentor, magnanimously, "but it really is awfully funny, you know! I can imagine your writing to the fathers of Pendlebury as one writes for the character of a kitchen-maid, and inquiring if their respective daughters are steady, sober, honest, clean, and obliging."

"You are very rude!" cried Jack, angrily; and then he marched home in a ferment of righteous indignation, feeling that he did well to be angry with such an insolent young woman.

After this - what with meeting him at dinner and garden-parties, and "sitting under" him at lectures - Violet Majendie saw a great deal of the new Headmaster, and the two became quite intimate enemies. She never grew weary of teasing him and putting him into a bad temper, and this custom of hers interfered with Jack's peace of mind more than a little. He continually writhed under her politely veiled ridicule, and felt it grow increasingly distasteful to him to select a wife from among the maidens submitted to his inspection. And, alas! his year of probation was fast drawing to a close.

"Of course, you'll take no notice of that ridiculous stipulation of the governors," remarked Violet, airily, one day at a garden-party. "I should treat the whole thing as a huge joke if I were you."

"But I cannot treat it as a joke; I am bound in honour either to comply with the condition under which I accepted the appointment, or else to resign it."

"Bother honour! There is no one more stupid and tiresome than a man of honour; he is selfishly oblivious of everything and everybody else, and generally ends in sacrificing himself and all his friends on the altar of this most unsatisfactory Moloch. But if you cling to this effete tradition, why not marry Sophy Slater, and be happy as well as honourable?"

"How dare you say such things to me?"

"I could not love Sophy Slater so much, Loved I not honour more," misquoted Violet; whereat Jack turned on his heel in high dudgeon.

Not long afterwards it happened that Jack Mortimer again met Violet in Melton Woods.

"I have something to tell you, Miss Majendie," he said, after the ordinary greetings; "I have resigned my appointment, and arranged to leave Pendlebury at the end of next term."

"What on earth induced you to do such an idiotic thing as that?" cried Violet, in amazement.

"You partly, and partly my own common sense. After you had once pointed out to me what a ridiculous figure I cut, I realised that force of your observations, and decided that I could not go on making a fool of myself any longer. So you see you were unjust when you said I had no sense of humour, Miss Majendie; it was merely dormant till you roused it."

"I certainly made a joke at your expense, but I didn't mean it to be at the expense of your whole income, my dear sir; you are carrying my joke too far, believe me. Besides, what on earth can it matter to you whether I laugh at you or not?"

"It matters so much that I would rather throw up my means of livelihood than submit to it any longer."

For a moment Violet was silent; then, looking up with a very penitent face, she said softly:

"I am so awfully sorry. It was a shame of me to go on like that, but I never thought you really minded."

"Well, I did mind, you see; moreover, you were right, and your remarks - though hardly pleasant hearing - were salutary. But there is just one thing that I must say in my own defence: when I consented to that most undignified stipulation I knew nothing at all about the sacredness of love, and I thought that if I must have a wife, one woman would do as well as another. So I really was more ignorant than base after all."

"How did you discover what you call 'the sacredness of love'?" enquired Violet, with much interest.

"I shall not tell you."

"You needn't, because I know; I discovered it myself about the same time. We are like the two astronomers - I forget their names - who discovered the planet Neptune at the same moment from opposite sides of the globe."

"You needn't, because I know; I discovered it myself about the same time. We are like the two astronomers - I forget their names - who discovered the planet Neptune at the same moment from opposite sides of the globe."

"But we were not at opposite sides of the globe, you see; otherwise this mutual discovery might not have occurred," said Jack, very tenderly - too tenderly, in fact, for a Headmaster towards a pupil whom he had once longed to cane.

After a hiatus in the conversation which it is unnecessary to describe, Violet remarked:

"So you needn't throw up your appointment after all, you silly boy."

"By Jove, I never thought of that! I suppose I needn't. But you won't be at all a suitable wife for a Headmaster, you know, Violet."

"Of course not. Nobody but a fool would marry a 'suitable' wife, and even he couldn't love her. Besides, the word 'suitability' was not in the bond, so any sort of a wife will fulfil the requirements of the governing body. Even a child - or a man of honour - would have the capacity to see the sense of that."

And Jack saw it.

THE END

I would like to know more about Ellen Thorneycroft Fowler

I would love to read How I Began - A Chat with Miss Ellen Thorneycroft Fowler by Dorothy Nevile Lees

Click here to see a list of her works

If you would like me to e-mail you more short stories by Ellen Thorneycroft Fowler please contact me:

HOME

fell upon a day that the worthy governors of the Grammar School at Pendlebury were called upon to fulfil the onerous duty of selecting and electing a new Head-master. By the outlay of a few paltry hundreds a year they expected to retain the services of as much intellect, culture, knowledge, and experience as could be packed into some six feet of human flesh; and they further demanded that this six feet of packing-case should be endowed with the manners of a marquis and the cricketing prowess of a professional. To the inhabitants of another planet it might appear that the governors of Pendlebury School expected a good deal for their money; but anybody who knows anything about this "best of all possible worlds" will readily perceive that a sum whereat a prize-fighter or a ballet-dancer would be justified in turning up their respective noses is generous - nay, extravagant - compensation for the services of a mere wrangler or double-first. So Wisdom was justified of those of her children who had a place upon the governing body of Pendlebury School.

fell upon a day that the worthy governors of the Grammar School at Pendlebury were called upon to fulfil the onerous duty of selecting and electing a new Head-master. By the outlay of a few paltry hundreds a year they expected to retain the services of as much intellect, culture, knowledge, and experience as could be packed into some six feet of human flesh; and they further demanded that this six feet of packing-case should be endowed with the manners of a marquis and the cricketing prowess of a professional. To the inhabitants of another planet it might appear that the governors of Pendlebury School expected a good deal for their money; but anybody who knows anything about this "best of all possible worlds" will readily perceive that a sum whereat a prize-fighter or a ballet-dancer would be justified in turning up their respective noses is generous - nay, extravagant - compensation for the services of a mere wrangler or double-first. So Wisdom was justified of those of her children who had a place upon the governing body of Pendlebury School. Jack Mortimer was a man who didn't trouble his head about women at all. He regarded a wife very much as he regarded a sideboard - viz., as a useful piece of furniture which no middle-aged householder should be without, but which would prove a ridiculously troublesome and cumbrous trinket for a young man to drag all over the country with him. He was naturally at first somewhat staggered by the condition of his election; but he reflected that after all, in this overcrowded country of ours, appointments are increasingly hard to find and wives increasingly easy; so, after due deliberation, he accepted the Headmastership, with a Micawberish hope that something would turn up ere the year of probation was over. The governors were kind enough to say that, failing a wife, they would graciously accept a sister in her stead; but Jack had never had a sister in his life, and realised the fact that - though a man is never too old to take a wife - having a sister, like playing on the violin, is a thing which one must begin in early youth or not at all.

Jack Mortimer was a man who didn't trouble his head about women at all. He regarded a wife very much as he regarded a sideboard - viz., as a useful piece of furniture which no middle-aged householder should be without, but which would prove a ridiculously troublesome and cumbrous trinket for a young man to drag all over the country with him. He was naturally at first somewhat staggered by the condition of his election; but he reflected that after all, in this overcrowded country of ours, appointments are increasingly hard to find and wives increasingly easy; so, after due deliberation, he accepted the Headmastership, with a Micawberish hope that something would turn up ere the year of probation was over. The governors were kind enough to say that, failing a wife, they would graciously accept a sister in her stead; but Jack had never had a sister in his life, and realised the fact that - though a man is never too old to take a wife - having a sister, like playing on the violin, is a thing which one must begin in early youth or not at all. "Fond of boys, are you, Miss Grover?" replied Jack, perversely; "I wish I were!"

"Fond of boys, are you, Miss Grover?" replied Jack, perversely; "I wish I were!" As he sat smoking in his study late that night, he meditated upon what an helpmeet for a schoolmaster Sophy Slater would prove. Her common sense and efficiency knew no bounds; but as for making love to her...! Jack remembered two old horsehair sofa-cushions in the nursery at home, which he pretended were a little brother and sister, named respectively Blackie and Week. From his third till his sixth year he loved them with a devoted though unrequited affection, and felt deeply their harsh response to his fond embraces. It now struck him that making love to Sophy Slater would be quite as uphill work as performing the part of a loving brother to Week and Blackie; and he decided that he could not begin to play that long and dreary game over again.

As he sat smoking in his study late that night, he meditated upon what an helpmeet for a schoolmaster Sophy Slater would prove. Her common sense and efficiency knew no bounds; but as for making love to her...! Jack remembered two old horsehair sofa-cushions in the nursery at home, which he pretended were a little brother and sister, named respectively Blackie and Week. From his third till his sixth year he loved them with a devoted though unrequited affection, and felt deeply their harsh response to his fond embraces. It now struck him that making love to Sophy Slater would be quite as uphill work as performing the part of a loving brother to Week and Blackie; and he decided that he could not begin to play that long and dreary game over again. All this was very pleasant to Jack Mortimer until Violet Majendie joined the literature class; then a change came o'er the spirit of his dreams, for a ghastly suspicion dawned upon his mind that this cleverest of his pupils was laughing at him. Jack was by no means destitute of a sense of humour, and the terms of his election had tickled him a good deal at first, but as nobody else in Pendlebury seemed to see anything grotesque in it - and as jokes, like dinners, are all the nicer when they are not at one's own expense - Jack soon ceased to regard his position as being at all unusual or absurd. But when Miss Majendie came home to Pendlebury after an absence of some months, during which period the new Headmaster had come and seen and conquered the Grammar School, a disquieting idea crept into Jack's head that Violet had a keener sense of humour than an all-wise Providence, as a rule, allots to women, and that this keen sense whetted itself at his august expense. It was not that Miss Majendie was rude to him - she was far too well-mannered for that; but she had raised audacity to the level of a fine art, and could say the most impertinent things in the least impertinent manner. For instance, once when they were studying Tennyson's "Oenone," she asked him before the whole class, apparently apropos of nothing:

All this was very pleasant to Jack Mortimer until Violet Majendie joined the literature class; then a change came o'er the spirit of his dreams, for a ghastly suspicion dawned upon his mind that this cleverest of his pupils was laughing at him. Jack was by no means destitute of a sense of humour, and the terms of his election had tickled him a good deal at first, but as nobody else in Pendlebury seemed to see anything grotesque in it - and as jokes, like dinners, are all the nicer when they are not at one's own expense - Jack soon ceased to regard his position as being at all unusual or absurd. But when Miss Majendie came home to Pendlebury after an absence of some months, during which period the new Headmaster had come and seen and conquered the Grammar School, a disquieting idea crept into Jack's head that Violet had a keener sense of humour than an all-wise Providence, as a rule, allots to women, and that this keen sense whetted itself at his august expense. It was not that Miss Majendie was rude to him - she was far too well-mannered for that; but she had raised audacity to the level of a fine art, and could say the most impertinent things in the least impertinent manner. For instance, once when they were studying Tennyson's "Oenone," she asked him before the whole class, apparently apropos of nothing: "Allow me, Miss Majendie," said the Headmaster, grimly, raising his hat, but not attempting to shake hands; and after a great deal of trouble he succeeded in releasing the prisoner and drawing upon himself a shower of grateful speeches from the prisoner's mistress. But Jack was not to be beguiled out of his ill-humour so easily, as he was still smarting under a remark of Miss Majendie's, which had been repeated to him by the never-failing "kind friend" whose duty and delight it is to repeat such unflattering comments. So in reply to Violet's profuse thanks he merely said:

"Allow me, Miss Majendie," said the Headmaster, grimly, raising his hat, but not attempting to shake hands; and after a great deal of trouble he succeeded in releasing the prisoner and drawing upon himself a shower of grateful speeches from the prisoner's mistress. But Jack was not to be beguiled out of his ill-humour so easily, as he was still smarting under a remark of Miss Majendie's, which had been repeated to him by the never-failing "kind friend" whose duty and delight it is to repeat such unflattering comments. So in reply to Violet's profuse thanks he merely said: "You needn't, because I know; I discovered it myself about the same time. We are like the two astronomers - I forget their names - who discovered the planet Neptune at the same moment from opposite sides of the globe."

"You needn't, because I know; I discovered it myself about the same time. We are like the two astronomers - I forget their names - who discovered the planet Neptune at the same moment from opposite sides of the globe."