|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The American War for Independence: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Mistake That Became A Religion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Loyalist Perspective By Joseph A. Crisp II |

|

|

|

Causes and Motivations |

|

|

| The American War for Independence, better known as the American Revolution, was the first, one of the longest and certainly the most important conflict ever fought by the modern United States. It brought a new country onto the world stage that was to have an enormous impact on world history, it also ultimately spurred on other revolutions around the world, with leaders imitating the American Founding Fathers from nations as far flung as France and Vietnam. It also divided the English-speaking world from one united empire into two separate world powers, a fact which was also to have a huge impact on peoples and nations all across the globe. |

|

| The American Revolution has also taken on a life of its own in many ways. Over the years, what began as a revolt by a few liberal elites and some street brawling vandals became the holiest of causes; a fact pressed home by the extremely harsh treatment meted out to those who dared voice opposition to it. Moreover, the often as not bungling American officers came to be sanctified, portrayed as legendary heroes with heaven-sent military genius. The fire-breathing, rabble rousing, treason spouting propagandists became the fathers of a just, noble and in every way "perfect" nation. |

|

|

| It was a war in which a fraction of men, organized by a handful of the wealthiest elites of the country, in the thirteen British North American colonies rose in an openly criminal, and originally unorganized revolt from the United Kingdom of Great Britain, personified by King George III, a monarch purposely slandered to fill the role of the first, great, black, villain in United States history. Along the way, a new government was formed, an experiment, supposedly, in liberal, deistic, enlightenment government, with philosophes as the statesmen and freemasons as the national priesthood. |

|

|

| The causes of the American Revolution, if looked at objectively, are far from sufficient to justify such a violent reaction. A picture of greed, bully tactics and social excess is painted of the British, when in fact, these traits seem to characterize the rebel colonists much better. While it is true that the winners write the history books, any, even slightly subjective look at the American Revolution will show what amounts to nothing less than a willful campaign of misinformation. The facts show beyond all doubt that the colonies were not suffering under a British tyranny; quite the opposite, they were left mostly alone and were enjoying great prosperity, in fact they enjoyed a higher standard of living than most people in the world, even in Great Britain. |

|

| What emerges is really a case of greed, yet another example of the same sort of mentality which caused the Protestant Reformation, described by the great English Catholic G. K. Chesterton as "the revolt of the rich". John Hancock, a leading revolutionary, was the wealthiest man in America in his time, Thomas Jefferson also had a reputation for high living which placed him deeply in debt (all of which he conveniently never had to pay after independence) and George Washington had married the largest landowner in Virginia, gaining land along with the huge estates the Crown had generously given him for his service in the French & Indian War, making him likewise one of the richest men in the colonies. These were certainly not suffering masses rising in revolt against an opulent oppressor. So much for that reason. |

|

| Another reason which is often presented was the proclamation of 1763, which the colonists complained hemmed them in, prohibiting their migration westward and thus denying them vast lands they somehow seemed to view as being pre-ordained by Heaven to belong to them. King George III had declared this land to be the sole property of the Native Indians who occupied it, and the British had nothing but the best interests of the colonies and the kingdom in mind with the proclamation. By reserving the land they occupied for the Indians, the British hoped to prevent further conflict with the natives. Today, looking back, we can see what a great number of lives could have been saved by this decree by preventing further antagonism among the occupants of America. |

|

| There were other laws passed by Parliament that the colonists didn't like as well. The Sugar Act was an often cited example. What many books don't tell you is that the Sugar Act was never really enforced. The Stamp Act is another example. In this case, the British repealed the Act simply to appease the colonists who became so outraged at the mere hint that they might be asked to contribute to paying the cost of their own defense. However, none of those stirring up anti-British sentiment seemed to ever be appeased, and soon the British government became concerned that they were losing control of their own colonies, and their subjects were straying from loyal opposition to outright treason. |

|

|

| Other acts were passed, but probably none was so hated as the Stamp Act. This required one to purchase a stamp for all legal documents. The colonists viewed this as a sort of "stealth tax", which was not far from the truth. However, the colonists had never paid taxes before and held that Parliament had no right to collect money from them because they were not represented in Parliament. However, the slogan, "No taxation without representation" was simply that: a slogan, and nothing more. When the colonies sent Benjamin Franklin to London as their unofficial envoy, he was told explicitly that under no terms whatsoever was he to accept any agreement which would give the colonies representation in Parliament. The reason for this was simple. The colonies were not being overtaxed. At the height of taxation, they paid only about $1.20 per year in taxes, while people in England were paying twenty-five times as much. The wealthy elites pushing for rebellion knew that they had a perfect position for making vast amounts of money, in fact they already had, but greed drove them to take measures to ensure not even the smallest amount would be paid back to the mother country. They knew that if they accepted representation, they would be easily outvoted and lose their highly privileged status, as well as losing the effective inflammatory cry of "taxation without representation is tyranny" and the public might not be so easily incited to take action on the behalf of the wealthiest merchants and businessmen in the colonies against the Crown. |

|

|

|

The Violence Erupts |

|

|

| Tension was further increased on the night of March 5, 1770. A large mob in Boston had surrounded a handful of British soldiers who had been sent to garrison the city to ensure law and order. There were 50 to 60 townsmen and no more than 10 redcoats. They began by hurling insults and profanity at the troops, and when this failed to provoke a response, they hurled snow and rocks. Under this painful, and intimidating barrage, someone fired a gun. With that shot, every soldier believing that the order to fire had been given, fired a volley into the mob. Five Bostonians were killed and six wounded. In a brilliant act of dramatic propaganda, the angry rabble-rousers dubbed this the "Boston Massacre", even though many ardent revolutionaries could see, and eventually proved, that the British troops were completely innocent of any wrongdoing and had only acted in self defense, out of fear for their own lives and safety. Paul Revere even fabricated a highly misleading illustration of the event, showing British troops, in battle lines, viciously firing into a crowd of peaceful colonists. Many never knew the truth of the situation, and assumed from this sort of propaganda that the British forces had simply murdered a "huge" number of peaceful Bostonians. |

|

|

| By this time, colonial outrage and civil disobedience in response to the Townshend Act taxes and the stamp tax had reached fervor pitch, thanks to other such effective uses of propaganda in portraying Britain as exploiting the hard working Americans, when in fact it was all arranged by the wealthiest colonists concerned that paying their fair share to the government might mean they would be slightly less wealthy. They also, more than simply being driven by greed, could see that this was an opportunity for political advancement, and so ambition also drove them forward as they saw the chance to become the rulers of a vast continent to further benefit themselves if they could turn popular opinion against what had up to this time been a country still called "home". |

|

| Great Britain however, despite their propaganda, was not a tyrannical power and was still willing to make concessions to ensure peace in America. Faced with colonial intransigence, Britain finally buckled, and hoping once again to appease the colonists, repealed all of the taxes except for the tax on tea. Once again, this act of good will did not work. The revolutionary leaders wanted all or none. In fact, the colonists would have had to drink a gallon of tea every day to pay only $1.00 a year in tax. It was a tax on a luxury item, which the colonists could have avoided paying by simply refusing to drink tea, and if not, it could not by any stretch be considered an oppressive tax. However, civil disobedience had worked before, so the colonial leaders were confident it would work again and that there was no limit to the distance Britain could be pushed. In fact, the British East India Company was already selling tea for the cheapest price around, but the colonial leaders still encouraged people to avoid buying any British goods to support the rest of the empire and instead spend even more of their money buying imports from the Dutch and other foreign powers. On December 16, 1773 a group of colonials, dressed as Mohawk Indians, attacked company ships in Boston harbor, taking and dumping more than 300 chests of tea into the water. Remember that these were not government ships, but the ships and property of a private company which these "Sons of Liberty" vandalized and destroyed. Purportedly organized by the Freemasons, this "Boston Tea Party" turned out to be the proverbial straw that broke the camel's back. |

|

| Up until now, the colonists had always managed to get what they wanted by misbehavior. Act after act, tax after tax, was repealed in order to appease the colonists and avoid an escalation of tensions in New England. After the tea party though, the British had reached the end of their rope, and decided that enough was enough. The Parliament now decided that it was time to take firm control of the colonies, remind them that law would be upheld, private property protected and to punish those responsible for such acts of wanton destruction and attempts to incite insurrection. The result was what was referred to as the "Intolerable" or "Coercive" Acts by the colonists. The British closed Boston harbor to all commerce until that city repented of their crimes. Naturally, Boston did not, and they refused to compensate the East India Company for the property they had destroyed. Lieutenant General Thomas Gage was sent with a British regiment to occupy Boston and the citizenry once again took to rioting. |

|

|

| 1774 also saw the passing of another act by Great Britain which enraged many in the colonies, though modern freedom-loving Americans might be shocked to hear why. This was the Quebec Act which granted religious toleration to the predominately Roman Catholic population of Canada. Prior to this time, as in Great Britain, Catholics had been denied most of their civil rights. However, when King George III granted the Canadians the freedom to worship without consequence, the radical Puritans of New England were outraged. Having long held hatred against the Anglican Church for being "too Catholic", showing any sort of fairness to the Church of Rome itself was seen as nothing less than the King of England making a deal with the devil. Radical Protestant preachers condemned the act and warned their paranoid parishioners that this was the first step toward a return to Catholicism and absolute monarchy; a totally absurd statement for anyone to make considering how seriously George III proved to take his coronation oath to uphold the established Church of England. However, it added fuel to the fire, again, it was an act granting tolerance, not intolerance, which most inflamed New England. |

|

| Also in 1774, the Continental Congress met for the first time. This was not a legal body, and had no legal power according to the law of the land. Their main purpose at this time was to denounce all British law and coordinate criminal activity against the government. To be sure, the meeting was couched in terms about freedom and liberty, but the simple fact is that it was simply an organization put together to act against the law and the legitimate government in America. However, if the colonists thought this would intimidate the British government, they were sadly mistaken. By now, Great Britain was becoming well acquainted with the actions of the so-called "patriot" groups, such as the "Sons of Liberty" who had been harassing Crown officials, vandalizing property and assaulting loyalists for years now. |

|

|

| Parliament now took a hard line. They declared the colonies of Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut to be in open rebellion and passed the Restraining Act. The colonists were barred from fishing off the Canadian coast and from trading with anyone outside of the British Empire. More troops were dispatched, and General Gage was ordered to arrest the rebel leaders, disperse any riotous mobs and to form a militia of those Americans still loyal to the British Crown, of whom there were many. |

|

|

| On the night of April 18, 1775 General Gage sent Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith with a troop of regulars to Concord, Massachusetts to destroy all long arms, artillery and ammunition being stockpiled by the enemies of the King. Many modern American conservatives point to this as the government attempting to "disarm" the colonists by taking away all of their means to defend themselves, usually mentioned in conjunction with some modern attempt by the government to limit the use of private fire arms. However, this is a totally misleading conclusion. What is often not mentioned is that these armaments were not private firearms, but were weapons which the British government had given to the colonial militias for their own defense. Given the recent actions of many in the colonies, there was nothing outrageous in Britain wanting to take back armaments they had given the colonists to prevent them being used against them. |

|

|

| Unknown to the British, the commander of a colonial spy ring, Dr. Joseph Warren, saw the redcoats leaving Boston. He then sent Paul Revere and William Dawes to spread the news. Messages were sent from town to town as the two riders raced through the countryside shouting, "the redcoats are coming, the redcoats are coming!" Colonial rebels, known as minutemen, grabbed their weapons and gathered at Lexington village. It is important to note, that the men referred to the oncoming troops as either "redcoats" or "regulars", not as "the British" since, despite all of the revolutionary rhetoric, most colonists still considered themselves to be British rather than Americans. On the continent, they identified with their colony, later state, but considered themselves to be British. |

|

| It was Major John Pitcairn who commanded the lead British companies. He saw the rebels gathering on Lexington green and he decided to lead his men there instead of directly to Concord. At dawn, the redcoats and Captain John Parker's colonials met on the town green. What is often not mentioned is that similar standoffs to this had taken place in the past, and each time, in order to avoid bloodshed, the British had backed down. This time, however, the British were resolved that a stand had to be taken or the American colonies would become lawless. The British fixed bayonets and advanced. Parker knew he was outmatched, but was still belligerent enough to order his men, "Don't fire unless fired on, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here". The British, hoping to avoid bloodshed if possible, were also ordered to hold their fire. Neither side flinched as the redcoats marched relentlessly nearer. The senior British officer called out, desperate to avoid conflict, "Lay down your arms!" followed by another redcoat who yelled, "You rebels disperse, damn you disperse!" |

|

|

| There were eighty colonists and around one hundred trained British regulars. Parker knew that if he fired on the King's soldiers, they would surely route his undisciplined mob and he would be charged with high treason. In the 18th Century, the penalty for treason tended to be on the stiff side, and it was becoming clearer by the second that this time, the British were not going to back down from the confrontation. Finally overcome with fear, Captain Parker decided such a bold stand was not worth his life, and he ordered his men to retreat. Just then, someone fired the famous "shot heard round the world". A redcoat fell wounded and the others leveled their muskets and loosed a volley, cutting down 18 colonists, 8 dead and 10 wounded. The rest of the colonists fled in a panic. Although it was never concretely decided who fired the first shot, it was almost certainly the colonists as it was only in their interest to spark a war, while the British were desperately trying to avoid conflict if at all possible. In any event, the regulars carried out their mission. The British marched on to Concord where they seized and burned 3 canon and 500 pounds of musket balls. The colonists, now warned and enraged by their defeat at Lexington, swarmed upon Concord and attacked in great numbers, forcing the British to withdraw back toward Boston. |

|

|

| As the British marched back to Boston, they were harassed every step of the way by about 3,000 rebels lining the woods on either side of the road. Their sniping was rather ineffective, but their overwhelming numerical superiority made up for it and British losses began mounting under the withering guerilla attacks. Before a relief column arrived to help them back to Boston, 270 redcoats were killed, wounded or missing. After this, there could be no denying the facts of the situation. War had come to North America. Previously organized militia cells sprang into action and converged on the British garrison in Boston. What started out as a simple effort to destroy munitions and arrest key rebel leaders had turned into an all out attack on the Crown forces in the northeast. |

|

|

| The numbers of colonials who descended on the British garrison were overwhelming. About 15,000 continental militia besieged the city of Boston. Lieutenant General Gage was then joined by 2,000 men and three major generals: William Howe, John Burgoyne and Henry Clinton. The colonists loved to note that the ship which brought the three men to Boston was HMS Cerberus, named after the 3-headed dog which guarded the gates of Hell. |

|

| About 1,500 colonists under Colonel William Prescott fortified Breed's Hill, near Bunker Hill, outside of Boston. Major General Sir Henry Clinton advised that the rebel entrenchment be attacked from the flank, but Gage decided to make a frontal assault, largely for symbolic reasons, to prove in a dramatic way the futility or revolution. General Howe launched the assault with 2,500 men, fusiliers, grenadiers, light infantry and royal marines. Embarrassingly, when one of the opening British canon shots, fired from a nearby warship, took off the head of one colonist, many of the rebels fled in panic before the first British soldiers ever appeared. Nonetheless, enough remained so that two attacks were repulsed, but each time the British reassembled and pushed back up the hill and on the third charge, the remaining colonists fled. This, the first major battle of the revolution, had been a British victory, albeit a costly one. The battle of June 17, 1775, called Bunker Hill, despite its actual location on Breed?s Hill, took the lives of some 1,000 redcoats and 400 colonists. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Both sides were somewhat shocked by the battle. The colonists were stunned by the resolve of the British troops their fire-breathing leaders had convinced them were so cowardly. They saw the British take extreme losses, and overcome two repulses to push back up the hill, keeping order and discipline despite the death and chaos around them as they closed ranks and pressed on. For the first time they realized that Britain was not to be pushed around, but was grimly determined. As a result, the colonists finally became a formal army and George Washington was given command, after attending the preceding convention wearing his decades old French & Indian War militia uniform, in brazen advertisement of his desire for the top command. The British were also surprised by how fierce a resistance the colonists had mounted, and knew that some changes were necessary. Due to the cost of the battle, Gage was recalled and General Howe was given command. The British knew that more troops would have to be sent, but in an age when crossing the Atlantic meant a hazardous 2-month voyage, this would take time. |

|

| These opening battles also succeeded in shoving war in the face of the British government, where many of the Whigs had been reluctant to take firm measures. Now there was no avoiding the issue: revolution had engulfed New England. King George III refused to deal with the revolutionary leaders, considering them to be simply criminals guilty of treason, and he declared all of the colonies to be in open rebellion. The British Parliament authorized a blockade of the American coast, and the enlargement of the army. Surprised by the ferocity of Bunker Hill, both sides prepared for the worst. |

|

|

| In America, while a standoff ensued at Boston, the colonials decided to expand the war. Almost as soon as the fighting broke out, rebel leaders made plans to invade Canada. Although this fact is also often ignored, the ambitious revolutionary leaders never intended their future nation to be limited only to the 13 colonies and their westward claims, but to include all of British North America, including Canada and the West Indies. The first British posts to be hit were Ft. Ticonderoga and Crown Point, which were taken without loss of life. Colonel Ethan Allen's "Green Mountain Boys" seizure of Ticonderoga is much romanticized, as it should not be. It was undoubtedly a helpful victory, but it was hardly a difficult one. The British were unaware that the war had started, it being only a few weeks after the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord, and so had posted only a single sentry while the rest of the garrison lay asleep. Rather than any ingenuity on the part of Ethan Allen, the fort was captured by simply walking in and taking possession. The real prize was the artillery, which was hauled overland to Boston and used to intimidate Howe into evacuating the city. It was though, pure bluff as Washington did not have the ammunition for a real bombardment. Naturally, the capture of Boston was hailed as a great victory as well, which it was not. The city held no strategic importance, the Royal Navy still controlled access to the port, and General Howe's whole army had escaped unharmed, accompanied by about 1,000 American loyalists who would have suffered the worst persecution had they stayed behind, and this army would eventually come back, better prepared and in even greater numbers. |

|

| Subsequently, plans were also put into effect to make Canada the so-called "14th Colony" of the American revolt. Although not often discussed today, the revolutionaries never had any intention of being content with their own colonies, but expected from the outset that their new nation would include the 13 colonies, Florida, the islands of the West Indies, all of the western territories up to the Mississippi River as well as Canada. The invasion of Canada was led by Colonel Benedict Arnold and Brigadier General Richard Montgomery. Opposing them was Lieutenant General Sir Guy Carleton with a small but disciplined and determined army of British troops, some Indians, Canadians and American loyalists. On November 13, Montgomery occupied Montreal, while Arnold advanced on Quebec. The rebels had expected the Canadians to flock to their colors and join their war against the mother country, but due to the pillaging of the Canadian countryside by American troops, Canada remained loyal. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

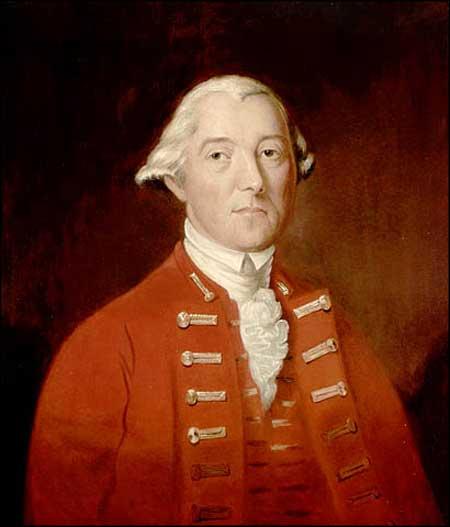

Sir Guy Carleton, Governor of Canada |

|

|

|

|

| Carleton, after escaping Montreal disguised as a fisherman, now faced Arnold at Quebec. However, Arnold's biggest problem was not Carleton, the city walls, or the King's soldiers, but the fierce Canadian winter and a lack of supplies. Montgomery joined Arnold, and the two decided they would have to attack, lest their entire army freeze or starve to death. During a violent snowstorm in the early hours of December 30/31, Arnold and Montgomery tried to storm Quebec. The British forces repulsed both attacks, inflicting heavy losses on the rebels. General Montgomery was killed and Arnold was wounded. At a cost of only 18 men, the British had inflicted 500 casualties on the rebels. Arnold, however, stubbornly refused to abandon the siege. It was not until May, 1776 when a 10,000-strong British relief force landed that Arnold took the skeletal remains of his army and retreated south to Ft. Ticonderoga with Carleton close at his heels. |

|

|

|

The Forces Involved |

|

|

| Throughout the American Revolution, there was a reoccurring theme, especially in the war's early years, but continuing to a lesser extent throughout. The colonials had the initial advantage of manpower at hand, thought it was a constant struggle to get the people to volunteer, and then most importantly, to persuade them to actually stay in the army long enough to have any effect. The British had the advantage of discipline and experience. The King's troops were mostly veterans of at least one other war, and they were obedient and well trained. This was their biggest difference with the American rebels. A German officer, Baron von Steuben, serving with the Continental Army wrote to a friend back in Prussia that, "In Prussia you tell a soldier to do something, and he does it. Here I have to say, this is why you should do that, and then he does it". |

|

|

| Battles were fought predominately with the smoothbore flintlock musket, eventually being the French Charleville for the colonists and the East India "Brown Bess" for the British. Much is often made of the colonial backwoodsman armed with the more accurate long rifle, but these weapons had drawbacks and did not make a significant difference in any engagement. Besides which, as it is often forgotten, the elite men of the British light infantry companies were armed with rifles as well and were generally just as proficient marksmen as any colonial soldier. |

|

|

| Civilians were, for the most part, left strictly alone by the regular armies during the war. Troops almost never fought battles at night, on Sunday, or in rainy weather (which would have rendered their flintlocks useless). Battles tended to be fought in open ground, with the enemies facing each other in long parallel lines, just as troops would in Europe. The two lines would march toward each other until they stood about 70 yards apart, then proceeded to kill each other. In toe-to-toe slugging matches like this, it was the disciplined army that won the day. The Americans were generally more flexible in these rules than the British, who condemned them for it, most British officers considering guerilla tactics to be cowardly. However, the idea that the Americans constantly out-fought rigid lines of British soldiers is utter nonsense. The Americans fought just as other conventional forces fought in Europe at the time, and most efforts to do otherwise ended in failure for them. |

|

| The Continental Army included regulars, men who had signed on for a specific term of service, as well as militia, volunteers who came and went as they pleased. Their training improved over time, but generally, throughout the war the militia was extremely unreliable and generally no match for British troops. Even in the final days of the war, American commanders advised their officers to surround militia with regular forces, in order to use deadly force to prevent them from running away after the first volley. The Crown forces in America, consisted of a variety of soldiers. There were the British regulars dispatched from the home islands, a number of Indian tribes who sided with Britain, who they regarded as a much greater friend than the land-hungry colonials, and the American loyalists who formed numerous regiments to aid the British cause. There was also the formidable Royal Navy and a number of mercenaries hired from several German principalities who were extremely skilled and professional. |

|

|

|

"The Empire Strikes Back" |

|

|

| With the end of 1775, it only looked as though the colonists had stirred up a hornet's nest. Their militia had fled in their first major battle, their invasion of Canada had ended in devastating failure and their only victories had been over small, outnumbered groups of British soldiers. Most importantly, the colonists had crossed a line it would not be easy to back down from. They had killed the King's soldiers, risen in armed revolt against their lawful government and disregarded all of the old laws. They were now faced with the truth that this would not be an easy war, and that their shows of force were now going to bring retaliation rather than concessions. The revolutionaries braced themselves, knowing it was only a matter of time before they felt the full fury of the Lion. |

|

| With the dawn of 1776, the only place the colonists could look to for hope was in the south. Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, after conducting a series of raids, was defeated in his former colony the previous December. In North Carolina, the Royal Governor Josiah Martin, with 1,000 Tories (American loyalists) met rebel militia at Moore's Creek Bridge on the way to Wilmington on February 27th. The loyal Highlanders, some wearing plaids and kilts, charged the rebels screaming, "King George and Broadswords!" only to be cut down by a withering fire and forced to retreat. |

|

|

| On March 3rd, a Continental fleet under Commodore Esek Hopkins seized New Providence Island in the Bahamas. Though this did help inspire faith in the fledgling Continental Navy, it was in no way a strategic or meaningful victory. The rebel flotilla never posed a serious threat to the Royal Navy at any time during the war. At present, Britain held control of the seas, and though rebel privateers might be a nuisance, British naval supremacy was never threatened. |

|

| Back on the continent though, the colonists soon found out what the British army had been doing since evacuating Boston, and all of the crowing and celebrating soon stopped. In June, the primary British army landed in New York, a city they would keep until the end of the war. There were 10,000 Royal Navy sailors and 32,000 army regulars, including 8,000 of the most professional, highly experienced soldiers in the world: Hessian mercenaries from Germany. This was the largest expeditionary force ever dispatched by the British Empire up to that time. |

|

| The British plan was a simple divide and conquer strategy. Sir Guy Carleton would march south from Canada and Howe would march north from New York dispersing any armed rebels, arresting their leaders and sending them to England to stand trial for their treason. General Howe had already declared martial law and King George authorized a naval blockade of the colonies and declared them to be in open rebellion, thus outside of the protection of Great Britain. |

|

| It is interesting to note that all throughout the war, though mostly in the beginning, America remained sharply divided on their reasons for fighting. Some sought total independence, others sought government reforms and some wanted dominion status within the British Empire. In 1776, officers of Washington?s staff still toasted the health of King George III and there were those who remained loyal no matter the circumstances. Thomas Hutchinson, a prominent loyalist, was one of those who expressed his disapproval of British actions and favored demanding greater autonomy for the colonies, but he absolutely drew the line at armed revolt, and when this happened went to England to act as an advisor to the King on American affairs. |

|

| By 1776 however, public opinion had changed a great deal. When the British army landed, and it was found out that the King had blockaded the coast and hired foreign mercenaries to fight the colonials, those supporting the revolution turned even more radical, urged on to a considerable degree by the inflammatory writings of a class of men who had become professional anti-British propagandists. So, on July 4th, the Second Continental Congress approved the official Declaration of Independence. The revolt was now aided by the appearance of a holy cause of a war for freedom. Nonetheless, most of the top British leaders were unconcerned. King George III said, "The dye is now cast, the colonies must either triumph or submit. I trust that they will come to submit". |

|

| At first, frustration followed. Benedict Arnold, leader of the failed invasion of Canada, assembled a small flotilla on Lake Champlain to face Carleton's British advance south. The Royal Navy, which disassembled their ships, hauled them overland and reassembled them on Champlain, easily wiped out Arnold's little fleet of amateur sailors. However, the delay this operation caused was significant and Carleton decided to return to Canada for the winter. New York though, was an entirely different matter. |

|

|

| On Long Island, on August 27th, General Howe launched a surprise attack on the small force of rebels sent to oppose him. The British defeated the colonists, easily, forcing them back behind the East River. Howe, in what would be a mistake he was to make again in the future, decided to pause briefly and Washington used the respite to order a retreat to Manhattan, but he was far from safe, though subsequent historians tend to portray all of Washington's retreats as some sort of brilliant strategic maneuver. |

|

| September 15th, Howe struck Manhattan. Washington desperately tried to stand and fight, but the British totally defeated the inexperienced colonists, many of whom simply broke and ran after the first volley. At last, Washington ordered another retreat. On September 22nd, Howe ordered the execution of the famous American spy, Nathan Hale, in New York City. Hale's last words became famous throughout American history saying, "I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country". |

|

|

| By October, there seemed to be no doubt as to the outcome of the war. The British regulars had broken the Continental militia at every encounter. The redcoats also refused to repeat Bunker Hill and attack an entrenched enemy by frontal assault. The numbers changed accordingly. At Long Island, in a series of stunning British victories, Howe lost only 400 men to Washington's 1,400. Yet, Howe was still planning an attack, albeit in a more thoughtful fashion. The British moved around the flank of the colonials by moving up Long Island Sound. However, once this move was discovered, Washington retreated yet again, this time to White Plains. There, on October 28th, British troops hit the rebels' right flank. The Americans put up a fairly good fight this time, but were still outmatched by the British and Washington ordered yet another retreat to higher ground. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

continue onward... |

|