Detranscendentalizing

Subjectivity:

Paul Ricoeur’s Revelatory

Hermeneutics of Suspicion +

À Jean-Claude Piguet

(1924-2000)

in memoriam

(+) This paper was

originally read before the Graduate Faculty of Philosophy of Marquette

University,

Abstract:

This essay seeks to outline the

development of Paul Ricoeur’s philosophical hermeneutics from a phenomenology

of the will towards a hermeneutics of revelation. It is shown how the radical

project of detranscendentalizing subjectivity, underlying the contemporary

French reception of a hermeneutics of suspicion, turns out to favor a

post-Hegelian return to Kant that recasts transcendental philosophy in a

historically, socially mediated correlation of language and subjectivity.

Key words: hermeneutics, language, revelation, subjectivity,

transcendental philosophy.

1. Introduction

In a highly polemical book on

the “French philosophy of the 1968 period,” Luc Ferry and Alain Renaut attacked

what they described as the French hyperbolic repetition of German thought,

especially in the supposedly radical antihumanism of Michel Foucault, Jacques

Lacan, Pierre Bourdieu, and Jacques Derrida’s respective appropriations of

Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Karl Marx, and Martin Heidegger.(1) The

authors identify the themes of the end of philosophy, the hermeneutic paradigm

of genealogy, the disintegration of the idea of truth, and the historicizing of

categories as tortuous paths ultimately leading to the annihilation of universals and, above all, to the oft-celebrated death of

the subject. Interestingly enough, Ferry and Renaut strategically decided to

spare other French thinkers who were also very influential in the sixties, such

as Emmanuel Levinas, Raymond Aron, Jean Beaufret, Jacques Bouveresse, Louis

Althusser, and Paul Ricoeur, precisely because they either did not succumb to

the politically irresponsible interpretations of May 1968 or did subscribe to

some form of humanism –that was especially the case of Jean-Paul Sartre. To be

sure, postmodernists and poststructuralists have also come under attack by

heralds of modernity on the other side of the

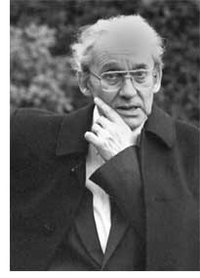

The name of French philosopher

Paul Ricoeur has been often associated with the existential phenomenology of

the 1950’s and with the hermeneutical philosophies of the 1960’s and ‘70’s.

Ricoeur’s transition from transcendental phenomenology to philosophical

hermeneutics, in continual dialogue with a myriad of different disciplines such

as psychoanalysis, structural anthropology, history, theology, social sciences

and linguistics, has very often been regarded as an eclectic philosophizing. In

point of fact, Ricoeur’s répertoire

is very broad and his compositions very intricate and nuanced. His dialectical

way of reconciling both ancient and modern thinkers, analytical and continental

traditions, and the architectonic structure of his writings and lectures, as

Henri Blocher has put it, characterizes Ricoeur as “l’homme des nuances, dites

avec un charme discret,” the Jaspersian maestro of a veritable Symphilosophieren. (2) And yet Ricoeur

has been careful enough to repudiate constant charges of “eclecticism,” which

he dismisses as “la caricature de la dialectique.”(3) Whether his

dialectic can really account for the metaphilosophical itinerary of his

philosophy of language remains, however, an open question. In a broad sense,

this question has to do with Ricoeur’s work as a historian of philosophy and as a philosopher who questions

everything, but in particular the very meaning of questioning itself or

problematizing --“philosopher c’est

problématiser.”(4) Within an established Cartesian tradition, the Cogito

explores the world and the subject’s alienation from it. Following Husserl and

his maître à penser Gabriel Marcel,

Ricoeur questions the Cogito’s insertion within the world, at once as

consciousness of being-in-the-world and as finitude in her/his appropriation of

it, by intending, yet undergoing the experience of the world. The question of

transcendental subjectivity and the very meaning of positing the I-world

opposition, co-constitution and correlation arise thus at the heart of

Ricoeur’s phenomenological explorations. Now, in a more specific, existential

sense, the hermeneutical question arises out of religious symbolism: “Le

symbole donne à penser” (“the symbol sets us

thinking.”) Kant, Hegel, Husserl, Heidegger, and biblical hermeneutics lead

Ricoeur to think the religious anew, to reflect upon the nature of the language

of faith. The classic problematic of “faith and reason” acquires then a

decisive hermeneutical orientation, in that the Cogito doubts, suspects, and

believes. We can no longer take “consciousness” for granted --including our

innermost religious convictions and feelings--, since there is also a “false

consciousness,” as “consciousness, far from being transparent to itself, is at

the same time what reveals and what conceals,” and this very dialectic calls

for a hermeneutics.(5) The “ethical”

lies, therefore, at the bottom of Ricoeur’s hermeneutic, insofar as it seeks

“to distinguish the true sense from the apparent sense,” and as “a proper

manner of uncovering what was

covered, of unveiling what was

veiled, of removing the mask.”(6) Following Heidegger, Ricoeur seeks to think

the unveiling thrust of language prior to the experience of subjectivity and

consciousness, as language itself reveals the existential structure of human openness

to the world. Like Hegel and Heidegger, Ricoeur attempts at rethinking

“revelation” (Offenbarung) in the

very becoming of self-consciousness, so as to highlight the transcending of

coming into being. Unlike Hegel and Heidegger, however, Ricoeur does not

believe that the Judeo-Christian paradoxical conception of an eternal God who

intervenes in temporal history is in need of a totalizing metapysics or has

become an obsolete onto-theological paradigm. As we shall see, Ricoeur’s wager

is that the revelatory nature of metaphors, especially in mythical and poetical

accounts, can actually be very helpful to rescue the radicalness of a

hermeneutics of alterity, a hermeneutics that resists systemic closure and that

refers to the complex, existential situations of our human reality, including

natural languages, mythologies, literature, and the cultural products of

civilizations. Ricoeur’s poses thus the hermeneutic problem in

metaphilosophical terms, say, analogous to Tarski’s convention T: (T) “p” is true

in L, iff p, where “p” is the sentence stating a certain proposition in a

certain object language L and p is the translation of that sentence into the

metalanguage. In contrast with Tarski’s theory of truth, which deals with

languages that are not semantically closed, Ricoeur’s hermeneutic phenomenology

follows Heidegger’s attempt to account also for non-propositional language so

that the hermeneutical transformation of

phenomenology is itself intertwined with methodological and conceptual

enlargements of signification that are reflected in the very conception of

metaphors and metaphoricity. Although I cannot pursue this further, I think

that Ricoeur has correctly spotted the hermeneutic transformation of

phenomenology in Husserl’s Logical

Investigations and his shift from Ideas

I to the generative phenomenology of the Lebenswelt and in the earlier Heidegger’s interest in a

phenomenology of formal indication (formale

Anzeige). I reformulate thus the

Ricoeurian problematic in the following terms: to what extent does Ricoeur’s

metaphilosophizing unveil some kind of revealing

language? And what is, after all, the nature of such a language of revelation?

What is the revealing function of the hermeneutical circle? These questions and

problems will underlie my hermeneutical investigation throughout this paper.

The main purpose of this modest study is to understand the place of Ricoeur’s

conception of “revelation” in his hermeneutical philosophy, especially in the

earlier writings leading to his own alternative variant of a post-Heideggerian

phenomenological hermeneutics. In order to situate Ricoeur’s conception of

revelation within the hermeneutical development of his philosophy, I shall

recapitulate his thinking along the chronological

order of publication of his main writings. Certainly, it is beyond the scope of

this exposé to examine all the subtle nuances of Ricoeur’s philosophy of

language and all the innumerable theological approaches to the problem of

revelation. I shall confine myself to outlining the evolution of Ricoeur’s

hermeneutic philosophy and its implicit language of revelation. In order to

better understand the place of religious language in Ricoeur’s thinking, I

shall examine his rnethodological shift from an existential, perceptualist

phenomenology towards a linguistic phenomenology, that is, how an implicit

hermeneutics of finitude gradually evolved into an explicit hermeneutics of

suspicion. This first part of the paper will cover three main stages in the

evolution of Ricoeur’s hermeneutical reflection (namely, l’eidétique, la symbolique et l’herméneutique). That will provide

the necessary background to articulate theological and philosophical

hermeneutics within the much broader framework of hermeneutics tout court, so that the particular

function of revelation calls for the interpretation

of texts and contexts.

2. The Phenomenology of the Will

As David Klemm has pointed out,

“only relatively lately has Ricoeur undertaken to write a comprehensive

hermeneutical theory based on a philosophy of language.”(7) However, as we

approach Ricoeur’s earlier writings within the broader perspective of his own

phenomenology, it seems that the hermeneutical question has prevailed along the

evolution of his thought, even before culminating in what has been saluted as a

“phénoménologie herméneutique.” Ricoeur confesses that he received “le choc

philosophique décisif” from his Socratic master Gabriel Marcel, but it was the

influence of the Husserlian method that guided his first attempt to construct a

phenomenological “philosophie de la volonté.” As he himself

would explain later in a famous collection of hermeneutical essays, Le conflit des interprétations (1969):

“My purpose here is to explore the paths opened to contemporary philosophy by

what could be called the graft of the hermeneutical problem onto the

phenomenological method.”(8) “La greffe du problème herméneutique sur la

méthode phénoménologique” --a programmatic formula to be retained—translates

indeed Ricoeur’s mediation between the Heideggerian, hermeneutical ontology of Existenz and the modern hermeneutical

theory which has been associated with Schleiermacher and Dilthey. The name of

Husserl should appear then in between, as what has been described by Ricoeur

himself as a “phenomenological detour.” Beyond the Cartesian Cogito (res cogitans) and the Kantian judging

consciousness (transcendental ego),

Husserl sought to relocate the thinking and living ego in its own correlative

milieu of consciousness, the Lebenswelt

(le monde vécu), so that the

transcendental Cogito remains “inserted and involved in the dense world of

human life,” which he calls the Welterfahrendesleben(“life-experiencing-the-world”).(9)

The ultimate meaning of such a transcendental ego is to be found not in the

material ego, Mensch, but in the ego

qua subject to the world, “exterior”

to the world yet “oriented” towards it. The objectivity of the world becomes

thus a “transcendental intersubjectivity,” in which the problem of the other

will always point to the transcendental ego, that is, in a descriptive analysis

which Husserl has called a “phenomenological reduction” (epoché), Einklammerung (“bracketing”). According

to Husserl, in this reduction both the transcendental ego and the

world-phenomenon intended by this consciousness (Intentionalität) reveal, as it were, the very meaning of their

relationship (ego-cogito-cogitatum).

Ricoeur’s phenomenology attempts thus to

articulate this signification in terms of being-in-the-world, however moving

away from every transcendental founding on the part of the Cogito and yet

always returning to a transcendental, reflexive attitude in its

self-understanding. Thus Ricoeur will not forgive the Platonism of the early

Husserl, although he will also regret that the later Husserl almost abandoned

his original “phenomenology of signification” on his way to an idealistic

“transcendental phenomenology.” Commenting on Husserl’s “analysis of

signification” in the second volume of his Investigations,

Ricoeur says:

It is important to notice that the first question of phenomenology

is: What does signifying signify? Whatever the importance subsequently taken on

by the description of perception, phenomenology begins not from what is most

silent in the operation of consciousness but from its relationship to things

mediated by signs as these are elaborated in a spoken culture. The first act of consciousness is designating or

meaning (Meinen). To distinguish

signification from signs, to separate it from the word, from the image, and to

elucidate the diverse ways in which an empty signification comes to be

fulfilled by an intuitive presence, whatever it may be, is to describe

signification phenomenologically.(10)

In part, the importance of these

remarks resides in the implicit critique Ricoeur was addressing against the

existential phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty, in defense

of the eidetic description he had employed four years earlier to compose the

first volume of his “philosophie de la

volonté,” Le volontaire et

l’involontaire (1950). In the “Introduction” to his French translation of

Husserl’s Ideen I (1950), Ricoeur had already criticized Merleau-Ponty’s existential use of phenomenology to reconquer the “facticité”

of our “être-au-monde,” whose world has always already been out there.(11)

Since every consciousness is perceptual, Merleau-Ponty seems to assume too

hastily that the signifié has already

been appropriated as signifiant in

the experience of consciousness as corps

vécu, as though the finitude of the latter concurred with the cognition of

the former. Ricoeur thinks that Merleau-Ponty absorbed from the later Husserl

(notably Husserl’s Lebensphilosophie,

after the Krisis) an existential shift towards a “perceptual”

phenomenology (Phénoménologie de la perception,

1945) in which perception becomes “the prerequisite and genetic origin of all

thought processes”:

Reduction is no longer understood as the withdrawal of

consciousness from the world but as the revelation of the true sense of the

transcendence of the “thing” in relation to consciousness. Contrary to the

Platonic and subsequently Galilean tradition, which holds that true reality is

not what one perceives but what one measures and conceives, the thing perceived

recovers its presence, its sparkle, its marvellous

power of revelation. ...The transcendency of the thing is the relative

transcendency of a vis-à-vis in which consciousness goes beyond itself. Consciousness, defined by its

intentionality, bursts outwards, moves to where the things are.

Correspondingly, the world is “world-for-my-life,” the environment of the “living

ego,” and it has no sense apart from the “living present” in which the

commitment of the vivid now, in all its presence, is constantly renewed.(12)

Although Ricoeur would be

forever indebted to Merleau-Ponty’s holistic circularité between the “symbolism of the body” and “the play of

intersignification,” he thinks that Merleau-Ponty’s “return to the speaking

subject” does no justice to the co-constitutive character of language itself.

Although he often speaks of the impensé

in Husserl’s phenomenology, and despite his recognition of the excess of the

“signified” over the “signifying,” Merleau-Ponty seems indeed to maintain the

“sedimentation” and the “institution” of language as a corollary of his

perceptual phenomenology.(13) On the other hand, Ricoeur’s “phenomenology of

the will” attempted to respond to the Husserlian challenge of intentionally

representing (vorstellen) the

noetic-noematic structure of consciousness, posited in the Ideen. According to Husserl, affection and volition appear as

complex representations in the process of Fundierung.

In order to understand these “affective and volitive subjective processes,”

Ricoeur first applies the Husserlian method of description to the practical

functions of consciousness, before arriving at the “constitutive” power of

consciousness in Vorstellungen, and

he finally denounces “as naive the pretensions of the subject to set himself [sic] up as the primitive or primordial

being.”(14) The project of the Philosophie

de la volonté was originally conceived in three phases: in the first

volume, Le volontaire et

l’involontaire (ET: Freedom and

Nature), Ricoeur deals with the “eidetics of the will,” while the second

and third volumes would be respectively devoted to the “empirics” and the

“poetics” of the will. Only the second volume of his ambitious project was

published, in 1960, under the title Finitude

et culpabilité, in two separate parts: L’homme

faillible (ET: Fallible Man) and La symbolique du mal (ET: The Symbolism of Evil).

In the first volume, which he dedicated

to Marcel, Ricoeur sets out to articulate some kind of dialectical via media between the Sartrean

ontological dichotomy (être-pour-soi

subject / être-en-soi object) and the

“incarnation” (être-au-monde) of

Marcel’s existentialism. Without adhering to the Husserlian “Platonizing

interpretation of essences” and its “idealism of the transcendental ego,”

Ricoeur applies Husserl’s “eidetic reduction” to the domain of the will, which

is unveiled as consciousness (“vouloir

comme conscience”), as it diagnoses

the nature of the involuntary:

...The

initial situation revealed by description is the reciprocity of the involuntary

and the voluntary. ...The involuntary has no meaning of its own. Only the relation of the voluntary and the involuntary is intelligible.

Description is understanding in terms of this relation.(15)

This latent hermeneutic must dig up the meaning-structure which

underlies the prepredicative, prelinguistic “given,” in an explorative movement

that reminds of Husserl’s process of Rückfragen

(“backquestioning”), although Ricoeur also uses a Kantian delimitation to avoid

falling back into transcendentalism:

Pure description, understood as an elucidation of

meanings, has its limitations. The gushing reality of life can become shrouded

in essences. But while it may finally be necessary to transcend the eidetic

approach, we must first draw from it all that it can give us, especially

delimiting of our principal concepts. The words decision, project, value,

motive, and so on, have a meaning which we need to determine. Hence we shall

first proceed to such analysis of meanings.(16)

Just like Husserl, who had used

the term eidos to designate “the

immediately given structures of experience” (hence the German Wesenschau, “idea-perception”), Ricoeur

deploys an “eidétique de la volonté”

to effect his phenomenological analysis of the essential structures of human

being qua “être-au-monde.” Like

Husserl, Ricoeur takes the Cartesian Cogito as the starting point of his

phenomenology, proceeding from the “voluntary” to the “involuntary.” The

Husserlian notion of “intentionality” and his technique of “bracketing” inspire

Ricoeur’s “double abstraction” of the fault (“la faute”) and transcendence: the autonomous “je pense” is left alone to its own freedom, motivated by an

infinite drive, yet bound by a finite nature. Again, Kant’s limit-idea defines the paradoxical

character of Ricoeur’s phenomenology. Contrary to Husserl in his tendency to

reduce the world to the transcendental subject, Ricoeur thinks the dichotomy of

the subject and the object to be real, although metaphysically inconclusive. As

over against the objectifying empiricism of others, he maintains that, in order

“to understand the relations between the involuntary and the voluntary we must

constantly reconquer the Cogito grasped in the first person (le Cogito en première personne) from the

natural standpoint.”(17) Ricoeur affirms thus the “reciprocity of the voluntary

and the involuntary,” in the conciliation of nature (the “corps propre” which I am) with freedom (my appropriation of a

meaningful world through incarnation), as an alternative to the paradoxical

duality of the involuntary and the voluntary.(18) Of

course, although he goes beyond the psychological dualism of the subject and

the object, Ricoeur does not seek to overcome the duality of the involuntary

and the voluntary. For in the innermost center of the human will, Ricoeur

concludes, remains the existential paradox of the “chosen” and the “undergone”

(le paradoxe de l’existence choisie et de l’existence subie). Such is the Kierkegaardian

accent of Ricoeur’s dialectic of human freedom. Moreover, the human, rational

boundaries implied in the Ricoeurian phenomenology of the will reflect the

Lutheran heritage of his Kantian morality. After asserting that freedom is not

a pure act but activity and receptivity, Ricoeur sets up the “limit concepts”

of human freedom only to open its way to meaning and the Transcendence. The

last words in this volume remind us of the ontological regionality of the

human:

A genuine transcendence is more than a limit concept: it

is a presence which brings about a true revolution in the theory of

subjectivity. It introduces into it a radically new dimension, the poetic

dimension. At least such limit concepts complete the determination of a freedom

which is human and not divine, of a freedom which does not posit itself

absolutely because it is not Transcendence. To will is not to create.(19)

If Kant’s Kritik meant to bring about a Copernican revolution by restoring to

subjectivity its due (der Mensch qua

the transcendental “I” as the center of a gegenständlich

cosmos), Ricoeur seeks to perform “a second Copernican revolution which

displaces being from the center, without however returning to the rule of the

object.”(20) In this sense, the Ricoeurian dialectic compels us to postpone any

conclusive remarks about the nature-freedom paradox. In effect, Ricoeur

maintains from the outset that “a paradoxical ontology is possible only if it

is covertly reconciled.”(21) Such a

dialectical phenomenology is thus to be understood as “reconciliation,” as an

understanding reconcilement of the voluntary with the involuntary:

“...comprendre le mystère comme réconciliation, c’est-à-dire, cornme

restauration ...du pacte originel de la conscience confuse avec son corps et le

monde.(22) Even though his first major work does not contain an explicit

hermeneutic, it seems that Paul Ricoeur was already preparing the soil on which

he should construct his “empirique”

and “symbolique.” In point of fact,

as Blocher has remarked, the Ricoeurian “eidétique”

prefigured somehow his future philosophy of interpretation not only in its

“description” of the will, but also in the very phenomenological style --in

French, “caractère”-- of his writing.

For the occurrence of expressions such as “la

parabole de l’être,” “figure,” “métaphore,” and “analogie de la Transcendance,” serve to illustrate the hermeneutical

concern which permeates the Ricoeurian phenomenology of the will. But it was

only in the preface to the second volume, Finitude

et culpabilité,

that Paul Ricoeur employed the term “herméneutique”

for the first time, as an ensemble of deciphering rules applied to a world of

symbols. Of course this interpretive exegesis of the symbol is to be understood

against the mythico-symbolic background of the “symbolique du mal,” which constitutes the second part of Finitude et

culpabilité. If the eidetics of the will culminated in the “incarnate

freedom” of the human essentially understood, an “empirics of the will,” on the

other hand, should complete our understanding of the actual conditions of human

existence as reflected in consciousness and as we find them in non-reflected

expressions such as myth and symbol. Although L’homme fallible, the first

part of this volume, remains within the framework of a “descriptive

phenomenology,” i.e. a work of pure reflection, it has been aclaimed, along

with its sequel La symbolique du mal

as the “most perfect” book ever written by Ricoeur.(23) In its first part, the

problem of evil is thoroughly dealt with on the level of the “imaginaire,” as existentially reflected

in the human “conscience” (both

“consciousness” and “awareness”) of her/his finitude and fallibility, in

her/his “conscience de faute.”

Ricoeur’s perspective is that of an ethical world-view (“vision éthique du monde”), which presupposes the dialectical

interdependence between freedom and evil:

Tenter de comprendre le mal par la liberté est une décision grave; c’est la décision d’entrer dans le problème du mal par la porte étroite, en tenant dès l’abord le mal pour “humain trop humain.” Encore faut-il bien entendre le sens de cette décision, afin de ne pas en récuser prématurément la légitimité. Ce n’est aucunement une décision sur l’origine radicale du mal, mais seulement la description du lieu où le mal apparaît et d’où il peut être vu; il est très possible en effet que l’homme ne soit pas l’origine radicale du mal, qu’il ne soit pas le méchant absolu; mais même si le mal était contemporain de l’origine radicale des choses, il resterait que seule la manière dont il affecte l’existence humaine le rend manifeste. La décision d’entrer dans le problème du mal par la porte étroite de la réa1ité exprime donc seulement le choix d’un centre de perspective: même si le mal venait à l’homme à partir d’un autre foyer qui le contaminerait, cet autre foyer ne nous serait accessible que par son rapport à nous, que par l’état de tentation, d’égarement, d’aveuglement dont nous serions affectés; l’humanité de l’homme est, en toute hypothèse, l’espace de manifestation du mal.(24)

According to this ethical view, not

only is freedom the reason for evil but the “confession of evil” (“l’aveu du mal”) is also the condition

for the consciousness of freedom. Thus the ethical view of evil leads

inevitably to an interpretation of mythical significations, as in the “myth of

the Fall”: if it was the human being who has posited (posé) evil in the world, humans on the

other hand posited evil only because they succumbed to an adversary, alien

temptation. In other words, the positing of evil implies already the

victimizing of freedom by an Other: “en posant le mal,

la liberté est en proie à un Autre.”(25) Such an ambiguous structure of myth

requires an exegesis of the symbol, which inspires Ricoeur’s hermeneutic phenomenology.

3. Phenomenology of the Symbol

Commenting on Ricoeur’s transition

from his eidetic phenomenology of the will to his hermeneutic symbolism of

evil, Kohak evokes the Ricoeurian hermeneutical principle of pars pro toto symbolism (i.e. a two-layer

structure of meaning, growing from the partial to the total representation of

symbolic meaning) which, in De l’interprétation,

would be applied to the interpretation of dreams qua symbols and fully

developed into a veritable hermeneutics:

The task of hermeneutic phenomenology is precisely to

recognize the universal latent significance made manifest through the overt

meaning of myth and symbol. Thus a hermeneutics must combine the attitude of

trust with an attitude of suspicion, a willingness to listen to what is

revealed through the symbol and a suspicion which would protect it from being

misled by its overt meaning.(26)

The Ricoeurian project of

building up a phenomenology of the will had to undergo a radical methodological

change, in its transition from the eidetic analysis of L’homme faillible to the structural hermeneutic of La symbolique du mal. Ricoeur had already announced the boundaries of his

phenomenological method in Le volontaire et l’involontaire, when he was forced to “bracket” (mettre en parenthèses) both the fault

and the Transcendence in order to work out a “pure,” eidetic description of the

will. Now, as he moves from the “eidétique”

to the “empirique,” Ricoeur admits

that man’s transition from a state of “innocence” to a “faulty” condition

cannot be properly dealt with by any “empiric description” but requires what he

calls a “mythique concrète.” The

Ricoeurian project moves then in the direction of a philosophical reflection

upon the myth. The concept of fallibility opens up the way to the symbolic

language of the confession of faults, as humans are held in a dialectical

mediation between the finite and the infinite, caught up between their language

of analogies and their guilty conscience’s language of enigmas. The enigmatic

character of this “langage de l’homme faillible” requires, essentially and not

accidentally, an herméneutique

(i.e. “une exégèse du symbole qui appelle des règles de déchiffrement”). The

Kantian aphorism, “the symbol gives raise to think,” is then invoked to

translate the hermeneutical project of Ricoeur’s symbolism:

Cette herméneutique n’est pas homogène à la pensée

réflexive qui a conduit jusqu’au concept de faillibilité. On esquisse les

règles de transposition de la symbolique du mal dans un nouveau type de

discours philosophique dans le dernier chapitre de la seconde partie sous le

titre: “le symbole donne à penser”; ce texte est la plaque tournante de tout

l’ouvrage; il indique comment on peut à la fois respecter la spécificité du

monde symbolique d’expression et penser, non point “dernière” le symbole, mais

“à partir” du symbole.(27)

In his analysis of primary

symbols such as “souillure” (stain),

“péché” (sin), “culpabilité” (guilt), and of myths which systematize these symbols,

Ricoeur seeks to depict the unity of the paradoxical relation of man as agent

and patient, as act and fact, as voluntary and involuntary, as freedom and

nature. In dialogue with the phenomenology of religions (Mircea Eliade, G. van

der Leeuw et al.) and historical-critical theologies of our times (notably

Gerhard von Rad’s Überlieferungsgeschichtliche

Theologie), Ricoeur classifies the myths into four different types:

(i) those of the “original

chaos,” as in the Babylonian account of creation (“Le drame de la création et la vision ‘rituelle’ du monde”);

(ii) the “tragic myth,” and

those of the evil god (“Le dieu méchant

et la vision tragique de l’existence”);

(iii) the “adamic myth,” in

Genesis (“Le mythe ‘adamique’ et la

vision ‘eschatologique’ de l’histoire”);

(iv) the myth of the “exiled soul,”

as in the Orphic gnosis (“le mythe de

l’âme exilée et le salut par la connaissance”).(28)

The twofold conception of myth

as “parole” (as opposed to “langage”) and “récit” (“en lui le symbole prend la forme du récit”),

according to Ricoeur, implies a sequential relationship between symbols that

refer to time and to a concrete mode of existence:

Le mythe exerce sa fonction symbolique par le moyen

spécifique du récit parce que ce qu’il veut dire est déjà drame. C’est ce drame

originel qui ouvre et découvre le sens caché de l’expérience humaine; ce

faisant le mythe qui le raconte assume la fonction irremplaçable du récit.(29)

“Totalité du sens” and “drame

cosmique,” “genèse” and “structure,” the structural themes of the Beginning and

the End --these concepts characterize Ricoeur’s dialectical theology of

reconciliation, as he had already admitted vis-à-vis the mystery of the serfdom

of will, “l’énigme du serf-arbitre, c’est-à-dire d’un libre arbitre qui se lie

et se trouve toujours déjà lié, est le thème ultime que le symbole donne à

penser.”(30) Thus the phenomenology of La symbolique du mal grounds its hermeneutics upon the double

intentionality of myth and symbol: the Ricoeurian hermeneutics is then better

defined as the task of deciphering double-meaning symbolic expressions. Now, I

must recall that the Ricoeurian symbolism in question is not speculative but it

remains dependant on our human experience and its reflection upon the myth.

Ricoeur announces a third volume on the “philosophy of the fault” (in the

awaited Poétique de la voionté), where he would

deal with the so-called “symboles

spéculatifs.”(31) In his introduction to the Symbolism

of Evil he develops an entire “critériologie

du symbole” in order to arrive at some definition of the symbol in question. In

the first place, every authentic symbol comprises three dimensions: cosmic

(i.e. it always refers to a place or an aspsct of the universe), oneiric (it is

in the dream that one can bring out the passage from the cosmic function to a

psychic-function in a symbol) and poetic (“dans

la poésie le symbole est surpris au moment où il est un surgissement du langage”),

and these three forms are structurally intercommunicative. Ricoeur goes on then

to enumerate six approaches to what should be the essence of the symbol:

1. The

symbol is a sign: “ce sont des expressions qui communiquent un sens; ce sens

est déclaré dans une intention de signifier véhiculée par la parole.”

2. Symbols are opaque: “à l’opposé des signes techniques parfaitement transparents qui ne disent

que ce qu’ils veulent dire em posant le signifié, les signes symboliques sont

opaques, parce que le sens premier littéral, patent, vise lui-même

analogiquement un sens second qui n’est pas donné autrement qu’en lui... Cette opacité fait la profondeur même du symbole, inépuisable comme

on dira.”

3. The symbol is a primary intentionality which provides

analogically a secondary sens: “à la différence d’une comparaison que nous

considérons du dehors, le symbole est le mouvement du sens primaire qui nous

fait participer au sens latent et ainsi nous assimile au symbolisé sans que

nous puissions dominer intellectuellement la similitude.”

5. This “symbol” in question has nothimg to do with that

of the “symbolic logic,” but the former is the very opposite of the latter: “la

signification, par sa structure même (en même temps

fonctiom de l’absence et fonction de la présence), rend possible à la fois la

formalisation intégrale, c’est-à-dire la réduction du signe au

‘caractère’ (au sens leibnizien) et finalement à un élément de calcul, et la

restauration d’un langage plein, lourd d’intentionnalités impliquées et de

renvois analogiques à autre chose, qu’il donne en énigme.”

6. How shall one draw the line between “symbol” and

“myth”? “Je tiendrai le mythe pour une espèce de symbole, comme un symbole

développé em forme de récit, et articulé dans un temps et un espace non

coordonnables à ceux de l’histoire et de la géographie selon la méthode

critique; par exemple, l’exil est un symbole primaire de l’aliénation humaine,

mais l’histoire de l’expulsiom d’Adam et d’Eve du Paradis est um récit mythique

de second degré mettant em jeu des personages, des lieux, un temps, des

épisodes fabuleux...”(32)

In the conclusion of this

volume, Ricoeur inscribes himself within the hermemeutical circle sketched by

Schleiermacher and Dilthey, and reproduced in different domains by Leenhardt,

Eliade and Bultmann. In effect, the Marburger theologian is evoked several

times by Ricoeur throughout his later writings. Although Ricoeur shares the

former’s demythologizing program on the whole, the French philosopher rejects

the Bultmannian confusion of “démythisation” with “démythologisation.”

According to Ricoeur, Bultmann has rightly articulated the hermeneutical circle

in terms of Verstehen and Glauben, in that one has to understand

in order to believe insofar as one has also to believe in order to understand.

Understanding and interpretation are certainly conditioned by our

presuppositions, by our preunderstanding and by that which is “aimed at” in our

approach (the Heideggerian Woraufhin).

Therefore, belief is only made possible, for the postcritical subjectivity of

“modernity,” through the mediation of one’s self-understanding. It is in this

sense that understanding, from a hermeneutical standpoint, is mediation rather

than reconstruction, revelation rather than objectification. Furthermore, I

agree with Gary Madison in that “Ricoeur’s reflexive philosophy is not a

philosophy of consciousness, and the hermeneutical subject is not a

metaphysical subject.”(33) Thus the intrinsic demythologizing character of

every critique effects the deconstructive thrust of Heidegger’s Abbau, as Bultmann’s Entmythologisierung

recasts the entformalisiert sense of

Dasein’s facticity: “Toute critique

‘démythologise’ en tant que critique: c’est-á-dire pousse toujours plus loin le

départage de l’historique (selon les règles de la méthode critique) et du

pseudo-historique.”(34) In particular, the “historisch-geschichtlich” rupture

implied in Bultmann’s neo-Kantian criticism has opened up the way for the

liberation of the logos enclosed in

the mythos. Nevertheless, such

demythologization in the very pursuit of objective truth does not suppress the

myth but rehabilitates it, in its symbolic dimension. As Ricoeur remarks,

...C’est précisément em accélérant le mouvement de

“démythologisation,” que l’herméneutique moderne met au jour la dimension du

symbole, en tant que signe originaire du sacré; c’est

ainsi qu’elle participe à la revivification de la philosophie au contact des

symboles; elle est une des voies de son rajeunissement. Ce paradoxe selon

lequel la “démythologisation” est aussi recharge de la pensée dans les symboles

n’est qu’un corollaire de ce que nous avons appelé le cercle du croire et du

comprendre dans l’herméneutique.(35)

Hence we can speak of the

Ricoeurian distinction between “démythisatiom” and “démythologisation” in the

following terms: whereas the former means the radical suppression of the myth,

the latter seeks to denounce the historical naiveté of the pre-critical belief

in the myth. Ricoeur rejects the former, while Bultmann apparently confuses the

two. In point of fact, the notion of “de-mythologization” as the “de-objectification”

of myth is better understood if we compare Bultmann’s definition of Mythos with that of Hans Jonas, whose

work on Gnosticism inspired the former’s demythologization project in the

1940’s. According to Bultmann,

The real purpose of myth is not to present an objective

picture of the world as it is (ein

objektives Weltbild), but to express man’s understanding of himself in the

world in which he lives. Myth should be interpreted not cosmologically, but

anthropologically, or better still, existentially... The real purpose of myth

is to speak of a transcendent power which controls the world and man, but that

purpose is impeded and obscured by the terms in which it is experienced.(36)

Now, as we consider Jonas’s

identification between entmythologisiert

(“demythologized’) and entmythisiert

(“demythed”) to express the “logicized” language of human thought, as opposed

to the “hypostasized” language of myth, it becomes evident that such an

interpretation of mythology had to appeal to an existential terminology.

Because the kerygma should not be eliminated (Bultmann), the demythologization

should not be reduced to a mere suppression of mythology but consisted in the

interpretation of it (Jonas). In other words, Bultmann --just like Jonas-- does

not dispense with the mythological, but rather seeks to understand it in

existential, self-appropriating terms. The myth, on the other hand, has itself

to be sacrificed on the altar of reason so that the logos itself be

resurrected, at the very level of our human existence. This re-appropriation of

the logos by the understanding subject, vis-à-vis the symbolism of the myth,

was the kernel of Jonas’s approach to Gnostic mythology:

We first turn to an anthropological, ethical sphere of

concepts to show how the existential basic principle we have postulated, the

“gnostic” principle...is here in a quite distinctive way drawn back out of the

outward mythical objectification (der

äusseren mythischen Objektivation) and transposed into inner concepts of

Dasein (in innere Daseinsbegriffe)

and into ethical practice, i.e. it appears so to speak “resubjectivized.”(37)

It seems that Ricoeur’s

conception of “myth,” originated from his “dialogue” with Jaspers, Berdyaev,

Eliade, and Jung, is much broader and more adequate to be used in a philosophy

of language than the Bultmannian one. As Ricoeur would point it out in his

preface to the French edition of Bultmann’s Jesus

(1968), the “nonmythological” language of faith proposed by Bultmann does not

solve the hermeneutical problem of objectifying the meaning of the Dass (“this event of encounter”) which

follows on the Was (“on general

statements and on objectifying representations.”(38) Ricoeur is not

taking so much a stand against Bultmann as he wants to go further in a

linguistic direction overlooked by the latter. Accordirig to Ricoeur, “Bultmann

seems to believe that a language which is no longer ‘objectifying’ is innocent.

But in what sense is it still a language? And what does it signify?”(39) Like

the “new hermeneutic” movemerit which would emerge out of the post-Bultmannian

quest of the historical Jesus, Ricoeur re-invokes the object of this

hermeneutical inquiry in order to radicalize the demythologizing program. Yet,

unlike Ebeling and Fuchs, he critically avoids the Heideggerian identity

between an existential hermeneutics and an ontology of

understanding. In his search for a method which reconciles both the symbolic

use of myth and the signification of faith, Ricoeur concludes that, in the last

analysis, “kerygma can no longer be the origin of demythologization if it does

not initiate thought, if it develops no understanding of faith.” The question

that arises then is whether the kerygma can still be understood as both event

and meaning together, without falling into the “objectifying” aporia again:

This question is at the center of post-Bultmannian

hermeneutics. The opposition between explanation and understanding that came

from Dilthey and the opposition between the objective and the existential that

came from an overtly anthropological reading of Heidegger were very useful in a

first phase of the problem. But, once the intention is to grasp in its entirity

the problem of the understanding of faith and the language appropriate to it,

these oppositions prove to be ruinous. Doubtless it is necessary today to award

less importance to Verstehen

(“understanding”), which is too exclusively centered on existential decision,

and to consider the problem of language and interpretation in all its breadth.(40)

It would be imprecise, however,

to understand Ricoeur’s criticism of Bultmann as an attempt to avoid the

Heideggerian category of “historicality” (Geschichtlichkeit;

in French, “historialité”). For Ricoeur agrees with Bultmann as to the

existential appropriation of meaning in the geschichtliche

decision; nevertheless, according to Ricoeur, this geschichtliche appropriation “is only the final stage, the last

threshold of an understanding which has first uprooted and moved into another

meaning.” Ricoeur criticizes Bultmann for leaping over “the moment of meaning,”

which is “objective” and “ideal” (in the Husserlian conception of Sinn, which does not hold any place in reality, not even in

psychic reality). Ricoeur wants thus to emphasize “the semantic moment” and

“the objectivity of the text, understood as content --bearer of meaning and

demand for meaning-- that begins the existential movement of

appropriation.”(41) This should bring us back to the hermeneutic phenomenology

developed in the Symbolism of Evil.

In its conclusion, Ricoeur evaluates the postcritical impasse suscitated by the

modern hermeneutical circle: on the one hand, the symbolic and mythic

expressions of being have been defied by the critique towards an objectifying

language, having human being as the center of meaning (transcendental Cogito);

on the other hand, the first naiveté, that of belief in a divine-ordered

cosmos, has been suppressed by demythologizing programs only to culminate in

the metaphysical forgottenness of Being. Just as Kant’s Kritiken mark the end of pre-modern approaches to the metaphysics

of representation and the beginning of anthropocentric conceptions of

subjectivity that articulate the rational and the empirical realms of whatever

becomes object of human cognition, Heidegger sought to rescue the fundamental

ontological dimension that was lacking in transcendental subjectivity.

Nevertheless, Heidegger’s hermeneutical clue to account for the meaning of Being out of Dasein’s factual existence is far from

conclusive, as its historicality and linguisticality allow for open-ended

interpretations. Hence Ricoeur goes on to confess:

Est-ce à dire que nous pourrions revenir à la

première naiveté? non point. De toute

manière quelque chose est perdu, irrémédiablement perdu: l’immédiateté de la

croyance. Mais si nous ne pouvons plus vivre, selon la croyance originaire, les

grandes symboliques du sacré, nous pouvons, nous modernes, dans et par la

critique, tendre vers une seconde naiveté. Bref, c’est en interprétant que nous

pouvons à nouveau entendre; ainsi est-ce dans l’herméneutique que se noue la

donation de sens par le symbol et l’initiative intelligible du déchiffrage.(42)

4. The Hermeneutics of Suspicion

As we have seen, according to

Ricoeur, hermeneutics has emerged out of the pasage from a “pre-philosophical,”

mythical naiveté (“la première naiveté”) to a demythologizing, critical

understanding of our human existence (“la seconde naiveté”). In this sense,

Ricoeur’s phenomenology of the will is a propaedeutic to his philosophical

hermeneutics, and his philosophy can be properly called a “hermeneutic

phenomenology.”(43) For Ricoeur brings both ontology and epistemology together

onto the level of his hermeneutics of human being. Not only the classical

question “Qu’est-ce que l’être humain?,” but above all the hermeneutic question

“Qu’est-ce que l’être de l’être-humain?” runs through his explorations of

meaning, in a dialectical philosophical anthropology which reluctantly gives

way to an ontological hermeneutics vis-à-vis the problematic of speaking the

language of Being. In effect, it seems indeed that this “dialectique” makes

Ricoeur’s critique of metaphysics stand closer to Kant’s than to Heidegger’s,

in that its ethical dimension allows for the “symbolique” without any

transgression of the truth of Being, aligning Ricoeur’s “éthique” with

Levinas’s and Kierkegaard’s primacy of the Other over the thinking of the Being

of beings.(44) Furthermore, such an ursprüngliche ethical dimension constitutes the humanist character of Ricoeur’s

philosophical thought, which overtly assumes the Christian presuppositions of

his thinking in the form of a hermeneutic anthropology. Like Heidegger, Ricoeur

believes that language is the house of Being and human being its shepherd;

unlike the Messkirch philosopher, however, Ricoeur believes in a transcendental

“signifier” which refers to our human finitude and fallibility as much as it

does refer to our openness to the Other. Religion, according to Ricoeur and in

full agreement with his Kantian conception of morality, translates thus the

very hermeneutical circle which keeps us within the mystery of being, without

any warrant of finding our way out. For religion, as the ultimate expression of

a human desire to transcend oneself in encountering

the Other, makes no pretension to overcoming the hermeneutic circles that take

us from suspicion to belief. Religion reveals thus our human belonging together

with the language of being. Therefore, a critical religious attitude leads us

not to unbelief but to interpretation, even within the circle, so that our

understanding of ourselves and our spiritual vocation may be fulfilled in a

world where meaning comes into being. This is the “wager” (“le pari”) of

Ricoeur’s hermeneutics of suspicion, the phiiosophical wager that, following

“the indication of symbolic thought,” “I shall have a better understanding of

man and of the bond between the being of man and the being of all beings.”(45)

In this shift from a mythico-symbolic expression of human existence towards a

critical, philosophical hermeneutics of being, Ricoeur has stressed the

function of the consciousness of self which lies in the very transition from a

precritical to a postcritical subjectivity. The first stage of subjectivity

(the first naiveté) holds the primary symbol not as a “given” (“une donnée”) to

human being but as a telos (and Ursprung)

to be “aimed at” (visée) through

mythic expression. The second stage of subjectivity can be portrayed by the

Cartesian cogito but it was decisively won by the Kantian epistemological turn

in his critique of dogmatic metaphysics: “How do I know what appears to me as

it appears?” Such critical approach, in its destruction of the immediate,

symbolic meaning, constitutes the preamble to the “hermeneutics of suspicion”

which was practiced by Feuerbach, Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud. The structure of

selfhood is thus objectified in the conscious critique of subjectivity, and

subsequently suspected and unmasked in its “false-conscious” pretensions to a

full, self-transparent “consciousness.” Finally, the third stage of

subjectivity is attained with the emergence of a reflexive consciousness in a

“restorative” hermeneutic that mediates the content of symbolic consciousness

through the critical consciousness. Ricoeur employs here the Husserlian

phenomenological method to return to the Kantian epistemology: the subject is

no longer a transcendental ego, but a historical-existential “I” that

synthesizes direct self-world relations. As Klemm has summed it up, “the second

naiveté is grounded on the full appearance of reflexivity just because it

exists where the naive meaning is mediated through the critical

consciousness.”(46) The development of the Ricoeurian hermeneutical reflection

found its climactic point between 1965 and 1969, when were published,

respectively, De l’interprétation. Essai

sur Freud,

and Le conflit des interprétations. Essais

d’herméneutique. It is in Freud and Philosophy (ET, 1970) that

Ricoeur makes explicit the challenge of a “hermeneutics of suspicion,” as

opposed to a primitive naiveté-based “hermeneutics of recollection” which tries

in vain to explain the symbolism of evil. First of all, in this book Ricoeur

announces the challenges imposed by the complexity and vastness of the realm of

language today:

Language is the common meeting ground of Wittgenstein’s

investigations, the English linguistic philosophy, the phenomenology that stems

from Husserl, Heidegger’s investigations, the works of the Bultmannian school

and other schools of New Testament exegesis, the works of comparative history

of religion and of anthropology concerning myth, ritual, and unbelief --and finally, psychoanalysis.(47)

“Le domaine

du langage,” says Ricoeur, “is an area today where all

philosophical investigations cut across one another.” In his penetrating

analysis of Freud’s hermeneutics of the sei?, Ricoeur marks off his own project

of interpretation of signs by taking a “longue route” that differs from the

“short cut” taken by Heidegger, in the latter’s definition of Dasein as the

being which has its being in understanding. Commenting on Heidegger’s

ontological hermeneutics, Ricoeur remarks that

One does not enter (Heidegger’s) ontology of understanding little by

little: one does not reach it by degrees, deepening the

methodological requirements of exegesis, history, or psychoanalysis: one is

transported there by a sudden reversal of the question.

Instead of asking: On what condition can a knowing subject understand a text or

history? one asks: What kind of being is it whose

being consists of understanding? The hermeneutic problem thus becomes a problem

of the Analytic of this being, Dasein, which exists through understanding.(48)

Nevertheless, it would be a gross mistake to simply

oppose Ricoeur’s reflective hermeneutics to Heidegger’s ontological hermeneutic

as though the former were not following the Denkweg

of the latter:

Je ne dis pas que la

théologie doit passer par Heidegger. Je dis que, si elle passe par Heidegger, c’est par-là

et jusque-là qu’elle doit le suivre. Ce chemin est le plus long. C’est le chemin de la patience et non de la hâte et de la précipitation. Sur ce chemin, le théologien ne doit pas être pressé de savoir

si l’être, selon Heidegger, c’est Dieu, selon la Bible. ...tout cela reste à

penser. Il n’y a pas de plus court chemin pour joindre

l’anthropologie existentiale neutre, selon la philosophie, et la décision

existentielle devant Dieu, selon la Bible. Mais il y a le long chemin de la

question de l’être et de l’appartenance du dire à l’être.(49)

This “longue route” typifies Ricoeur’s hermeneutics as

an “herméneutique du détour,” in that his philosophy

of the “sujet” meets “le long détour des signes” as it proceeds from the “je

suis” to the “je pense.” For Ricoeur, “la réflexion est l’effort

pour ressaisir l’Ego de l’Ego Cogito dans le miroir de ses objets, de

ses oeuvres et finalement de ses actes.”(50) The hermeneutical detour compels

the existing cogito to appropriate its own existential meaning not in a

reflection objectified, as it were, “thought” outside its being, but in the

very interpretation of those signs which anticipated its reflection upon

existence. According to Ricoeur,

The ultimate root of our problem lies in this primitive connection

between the act of existing and the signs we deploy in our works; reflection

must become interpretation because I cannot grasp the act of existing except in

signs scattered in the world. That is why a reflective philosophy must include

the results, methods, and presuppositions of all the sciences that try to

decipher and interpret the signs of man.(51)

That leads Ricoeur to concentrate his hermeneutical

project upon the textual approach: instead of reducing itself to an ontology of understanding, hermeneutics has to deal with

the object of interpretation par excellence, the text, and its subject matter (Sache). The “longue route du détour”

impels Ricoeur to immerse deeper and deeper into an existential-structural

understanding of the sense, more precisely of the “double sense”:

“l’interprétation c’est l’intelligence du double sens.”(52)

As he thoroughly explores the Freudian theory of interpretation, he precises

the “hermeneutical field” containing the psychoanalysis (interpretation of

dreams as symbols) but inscribed within the broader sphere of a general science

of signs:

Ainsi, dans la vaste sphère

du langage, le lieu de la psychanalyse se précise: c’est à la fois le lieu des

symboles ou du double sens et celui où s’affrontent les diverses manières d’interpréter. Cette circonscription plus vaste que la

psychanalyse, mais plus étroite que la théorie du langage total qui lui sert

d’horizon, nous l’appellerons désormais le “champ herméneutique”; nous

entendrons toujours par herméneutique la théorie des règles qui président à une exégèse, c’est-à-dire à l’interprétation d’un texte

singulier ou d’un ensemble de signes susceptible d’être considéré comme un texte...(53)

Hermeneutics is thus the process of deciphering which

goes from manifest content and meaning to latent or hidden meaning. The “text,”

object of interpretation, is to be taken here in a very broad sense: symbols as

in a dream, myths and symbols of society (as in religious, cultural, and social

contexts), literary texts, and so forth. Ricoeur goes on to assert, after

Cassirer’s conception of das Symbolische, that it is precisely because of the distinction between “les expressions univoques”

and “les expressions multivoques” that the symbolic function makes hermeneutics

possible and necessary. “Vouloir dire autre chose que ce que l’on dit, voilà la

fonction symbolique.”(54) In effect, the equivocal symbols (as opposed, say, to

the univocal symbols of symbolic logic) constitute the true focus of

hermeneutics. As he would define it in an article that has become a classic of

hermeneutic theory (“Existence et herméneutique,” 1965, reprinted in Le conflit des interprétations):

I define “symbol” as structure of signification in which a direct,

primary, literal meaning designates, in addition, another meaning which is

indirect, secondary, and figurative and which can be apprehended only through

the first.

And he adds,

Interpretation, we will say, is the work of thought which consiste in

deciphering the hidden meaning in the apparent meaning, in unfolding the levels

of meaning implied in the literal meaning. In this way, I retain the initial

reference to exegesis, that is, to the interpretation of hidden meanings.

Symbol and interpretation thus become correlative concepts; there is

interpretation wherever there is multiple meaning, and it is in interpretation

that the plurality of meanings is made manifest.(55)

It is revealing that the Ricoeurian detour of semantics appears to be a

hermeneutical, dialectical response to the Heideggerian ontological

concentration. Ricoeur’s epistemological concern here is to avoid the

temptation of separating “vérité” and “méthode”(56)--as ironically implicated

by Gadarner’s Wahrheit und Method (1960)-- in order to properly

articulate the existential, unveiling meaning of an ontological understanding:

A purely semantic elucidation remains suspended until one shows that the

understanding of multivocal or symbolic expressions is a moment of

self-understanding; the semantic approach thus entails a reflective approach.

But the subject that interprets himself while interpreting signs is no longer

the cogito: rather, he is placed in being before he places and possesses

himself. In this way, hermeneutics would discover a manner of existing which

would remain from start to finish a being-interpreted. Reflection alone, by

suppressing itself as reflection, can reach the ontological roots of understanding.

Yet this is what always happens in language, and it occurs through the movement

of reflection. Such is the arduous route we are going to follow.(57)

The Ricoeurian conception of symbol is, in the words

of Richard Palmer, that of “a semantic unity which has a fully coherent surface

meaning and at the same time a deeper significance.”(58)“Semantics”

is to be understood here as the linguistic study of the principles of discourse

(“la linguistique du discours” as opposed to “la linguistique de la langue,”

following de Saussure’s distinction between “speech” (parole) and “language” (langue).

The sentence, combining noun and verb, allows humans to say something about

something (ti kata tinos):

because it conveys a message, it can thus be considered the basic unity of the

discourse (“l’unité de base du discours”). On the other hand, if one holds the

sign (phonological or lexical) to be the basic unity of language (in the sense “langue”), one should speak instead of “semiotics” as opposed to

“semantics”. In point of fact, the noun-verb duality at the level of the

sentence has been eclipsed by the duality of levels of language.(59) Ricoeur’s hermeneutics has constituted itself a

thorough critique of the semiotic monopoly, which has largely determined the success

of structuralist and contemporary linguistic researches. What Ricoeur’s

critical hermeneutics seeks to unmask is any pretension to a “structural”

dissolution of sense (including certain nihilistic forms of “deconstruction”

and “dissemination”) on the basis of objectified explanations of semiological

mechanisms. Such is the role of “suspicion” reserved to Ricoeur’s hermeneutics:

like les maîtres du soupçon Marx,

Nietzsche, and Freud, the continual task of the hermeneutist is to suspect any

given structure of “false consciousness,” and to unmask the “ideological”

pretensions to conclusive explanations of meaning.(60)

This hermeneutics of suspicion is in fact the effective, ongoing praxis of our demythologizing task to

continue progressing towards the second naiveté:

Thus hermeneutics, an acquisition of “modernity,” is one of the models

by which that “modernity” transcends itself, insofar as it is forgetfulness of

the sacred. I believe that being can still speak to me --no longer of

course, under the precritical form of immediate belief, but as the second

immediacy aimed at by hermeneutics. This second naiveté aims to be the

postcritical equivaient of the precritical hierophany.(61)

As I conclude this exposé on the development of

Ricoeur’s hermeneutics, I cannot proceed without conceding that the Conflit des interprétations is but the

beginning of a new, fertile phase of Ricoeur’s writings on hermeneutical

theory. It would be misleading, however, to exaggerate

the opposition of this “later” Ricoeur to an “early” one, for his entire

philosophical work, since the “Philosophy of the Will,” should be regarded as

an “oeuvre de maturité.” The methodological shift should thus be understood as

an evolution towards a more precise, enlarged definition of the hermeneutical

field, as Ricoeur specifies the primacy of the text and, at the same time,

maintains the open-ended extension of its textuality, for instance, in the

hermeneutical dialogue with the social sciences (62).

5. Conclusion: The Hermeneutics of

Revelation

Ricoeur’s post-Hegelian interpretation of Kant is the

hermeneutic effect of a dialectical post-Hegelian retour à Kant, following the phenomenological detours of

Heidegger’s critique of the onto-theological. For the manifestation of the gift

of Being, according to Heidegger, is not so much Offenbarung (“revelation” of transcendence) as Offenbarkeit, the “impersonal” unveiling of the Open (das

Offene), as an un-concealing dimension of Being in the “es gibt” of

all that is. The ethical is therefore subordinated to the ontological, as the

unconditional primacy of Being over all other beings (including “God”) is given

in language itself, as the event of appropriation between Being and human

Dasein, in that language reveals

their belonging-together (“das Zusammengehören von Mensch und Sein”).(63) Ricoeur reappropriates this “belonging-distanciation

dialectic” in his hermeneutics of the idea of revelation, by means of yet

another detour, “le détour du texte.”

Before anything, Ricoeur shows that the détour of the text is indeed a veritable

retour to the text and its world. I

shall confine myself to presenting three brief overviews of three main writings

which will serve to highlight the main thesis of this paper, namely, that the

evolution of Ricoeur’s hermeneutics of suspicion translates the revelatory

nature of his correlative conception of philosophical anthropology and

philosophy of language. The first one is the article “Qu’est-ce qu’un texte?

Expliquer et comprendre,” published in 1970 in the collection Hermeneutik und Dialektik: Aufsätze II,

edited by Bubner et al. (ET: “What is a Text? Explanation and Interpretation,”

in J. Thompson, Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences, 1981). In

“What is a Text?” Ricoeur deals with the “two basic attitudes which one

can adopt in regard to a text,” namely that of an “explanation” (Erklärung) and that of an

“interpretation” (Verständnis),

following a Diltheyan terminology. Ricoeur believes that such dichotomy has

nevertheless become obsolete in our days: if the structuralists, on the one

hand, aim at “explanatory” methods (language as a system of signs which

displays an objective structure), the “interpretative” attitude on the other

hand (language as speech, whose sense signifies a referent) follows the sense

of a text carried by its own structure. By stressing the nuances of such

distinction, Ricoeur goes on to affirm that these attitudes are no longer in

polar opposition (“aux antipodes”) to each other, but they can still serve as a

clue to what should be a hermeneutic “mediation” between erklären and verstehen.(64)

In order to arrive at this mediation we have to

articulate both “explaining” and “interpreting” with that which a text is. For

Ricoeur believes that hermeneutics proper springs from the problem of the text

conceived as a work.(65) In this sense, Ricoeur

asserts that “interpretation, before being the act of the exegete, is the act

of the text.”(66) The Ricoeurian notion of “text” includes, in effect, the

multiple modes of “distanciation” associated not only with writings but with

“the production of discourse as a work.” In brief, Ricoeur assigns to the

notion of text the same basic characteristics of discourse (the event-meaning

dialectic and the sense-reference relationship): texts refer thus to an

intended “world of the text” (le monde du

texte) and to the self as well.(67) Surpassing Dilthey’s Romantic

conception of Verständnis as

“appropriation,” Ricoeur goes on to reconcile both the semantic, concrete level

of discourse with the semiotic, abstract level of formal language at the same

hermeneutical level of what has been called a “fusion of horizons” (Horizontverschmelzung) —to use

Gadarner’s felicitous formula:

I shall therefore say: to explain is to bring about the structure, that

is, the internal relations of dependence which constitute the statics of the

text; to interpret is to follow the path of thought opened up by the text, to place oneself en route towards the

orient the text.(68)

Following this interpretation-explanation dialectic,

both the hermeneutical “belonging” (Zugehörigkeit)

and the critical, objectifying “distanciation” constitute together the

appropriation of the “world of the text”:

....Ultimately, what I appropriate is a proposed world. The latter is

not behind the text as a hidden

intention would be, but in front of

it, as that which the work unfolds, discovers, reveals.

Henceforth, to understand is to

understand oneself in front of the text. ...In this respect, it would be

more correct to say that the self is

constituted by the “matter” (Sache)

of the text.(69)

The second writing to be mentioned here, La métaphore vive (1975; ET: The Rule of Metaphor, 1977), as Ricoeur himself would

comment, “tackled the two problems of the emergence of new meanings in language

and of the referential claims raised by such nondescriptive language as poetic

discourse.”(70) These two problems were somehow already implicit in Ricoeur’s

early inquiry into the symbolic forms of discourse, which would be later

designated by “the complex problem of fiction and of productive

imagination.” The Ricoeurian conception of métaphore

is to be framed within the wider framework of the récit (the narrative) to which he attributes “the power of

reshaping human experience” more than any other “language games,” as the self

itself is mediated and constituted through first-person narratives in one’s

self-understanding. Because he maintains the distinction between the

philosophic-speculative and poetic-religious realms of discourse, Ricoeur

focuses on the latter in which figurative meaning outgrows literal meaning

(“the metaphoric process”):

Let us call any shift from literal to figurative sense a metaphor. If

the general sweep of this definition is to be preserved, it is necessary,

first, that the notion of change of meaning be not restricted to names, or even

to words, but extended to all signs. Furthermore, one must dissociate the

notion of literal meaning from that of proper meaning. Any lexical value

whatsoever is a literal meaning; thus, the metaphorical meaning is nonlexical: it

is a value created by the context ...An implicitly discursive trait follows,

which at the same time prepares for the entrance of resemblance: every

metaphorical meaning is mediate, in the sense that the word is ‘an immediate

sign of its literal senses and a mediate sign of its figurative sense’ (Michel

Le Guern, Sémantique de la métaphore et

de la métonymie, p.175). To speak by means of metaphor is to say something

different ‘through’ some literal meaning.(71)

Finally, Temps

et récit (3 vols., 1983-85) should be mentioned

here as one of the most recent magnificent attempts to reconcile praxis and poiesis in a single hermeneutics of the human subject. According to

Ricoeur, “the refiguring of time by narrative...is the joint work of historical

and fictional narrative.”(72) In Histoire

et vérité (1955), the problematic tension between subject and object

vis-à-vis the historical reality had already been submitted to the krisis of a “not-yet” Word: a

Judeo-Christian conception of history seemed to constrain the philosopher to go

beyond both existentialism and historicism, in an eschatological attitude of

hope.(73) Now, complementing his metaphoric theory, Ricoeur takes the defense

of “narrative time” against atemporal (and ahistorical), structuralist

narratives. With Aristotle, Ricoeur maintains that temporal narrative

represents human action in the world. Hence the term “récit” is to comprise

reader and text are kept in a dialogue which

culminates in the understanding of the text by the reader and the latter’s self-understanding

as being-in-the-world:

To understand these (narrative) texts is to interpolate among the

predicates of our situation all those sayings that, from a simple environment (Umwelt), makes world (Welt). Indeed we owe a large part of the

enlarging of our horizon of exlttenae to poetic works.(74)

It has become clear now that Ricoeur’s return to the

text reveals also an intriguing detour of ontology. In point of fact, Ricoeur’s

“reflective” philosophy opposes every “ontological” attempt to conclusively

appropriate the un-thought meaning-structure of being: “l’impensé reste

toujours à être entièrement pensé,” one will never exhaustively think the

totality of the unthought. Certainly, this character of finitude in Ricoeur’s

hermeneutics betrays not only an eschatological return to Kant’s “limiting

concept” but also a “proleptic” detour towards the transcendens. Such is again the Ricoeurian debt to Hegel’s

metacritique of Kant’s transcendental subjectivity. As Walter Lowe has

convincingly shown, the “regional ontology” of Ricoeur’s humanist “philosophy

of presence” is coherent with the Reformed dictum finitum non capax infiniti (“the finite is not capable of the

infinite”), so dear to Karl Barth and neo-Kantian theologians.(75)

Furthermore, it seems that Ricoeur’s mediating hermeneutics of metaphor seeks

to respond to Heidegger’s linguistic mysticism for the very insufficiency of

the latter’s appropriation of Luther’s finitum

capax. Thus, the elliptical shift from a “symbolique” towards a

“métaphorique” is quite revealing of Ricoeur’s ambitious dépassement of the later Heidegger, as we can infer from his

magisterial study on “Métaphore et discours philosophique” (last one in The Rule of Metaphor):

Le prix de cette prétention

(chez Heidegger) est l’ambiguité des dernières oeuvres, partagées entre la

logique de leur continuité avec la pensée spéculative, et la logique de leur

rupture avec la métaphysique. La première logique place l’Ereignis et le es gibt dans

la lignée d’une pensée sans cesse en voie de se rectifier

elle-même, sans cesse en quête d’un dire

plus approprié que le parler ordinaire,

d’un dire qui serait un montrer et un laisser-être, d’une pensée, enfin, qui jamais ne renonce au

discours. La seconde logique conduit à une suite

d’effacements et d’abolitions, qui précipitent la pensée dans le vide, la

ramènent à l’hermétisme et à la préciosité, et reconduisent les jeux

étymologiques à la mystification du “sens primitif.” ...Ce qui est caractérisé,

ici, c’est la dialectique même des modes de discours, dans leur proximité et

dans leur différence. D’une part, la poésie, en

elle-même et par elle-même, donne à penser l’esquisse

d’une conception “tensionnelle” de la vérité... Par ce

tour de l’énonciation, la poésie articule et préserve, en liaison avec d’autres

modes de discours, l’expérience d’appartenance

qui inclut l’homme dans le discours et le discours dans l’être.

D’autre part, la pensée spéculative appuie son travail sur la dynamique

de l’énonciation métaphorique et l’ordonne à son propre espace de sens. Sa réplique n’est possible

que parce que la distanciation, constitutive do l’instance critique, est

contemporaine de l’expérience d’appartenance, ouverte ou reconquise par le

discours poétique, et parce que le discours poétique, en tant que texte et oeuvre,

préfigure la distanciation que la pensée spéculative porte à son plus haut

degré de réflexion.(76)

It is, therefore, within the framework of a métaphorique that Ricoeur’s discours théologique seeks to respond to

Heidegger’s Destruktion der Onto-Theo-Logik:

“A travers métaphore et récit, la fonction symbolique

du langage ne cesse de produire du sens et de révéler de l’être.”(77) As

announced from the outset, I did not intend to explore Ricoeur’s “theological

hermeneutics” in this study but rather to articulate his “revelatory language”

in terms of his “hermeneutical reflection.” I shall conclude thus this paper

with Ricoeur’s own account of such an “herméneutique

de la révélation.”

In a lecture delivered for a “Symposium on the Idea of

Revelation” at the Faculté Universitaire St. Louis in

The intrinsic dialectic of deus revelatus / deus

absconditus accounts for the very idea of revelation, insofar as the Name

of Yahweh cannot be pronounced: ehyeh

asher ehyeh (literally, “I will be what I will be,” Exodus 3,14). Ricoeur

has rightly remarked that the Septuagint’s translation of God’s self-revelation

(“I am who I am”) “opened up an affirmative poetics of God’s absolute being

that could subsequently be transcribed into Neoplatonic and Augustinian

ontology and then into Aristotelian and Thomistic metaphysics,” including Arab

thought.(82) As over against this metaphysical, onto-theological

rationalization of biblical revelation, Ricoeur takes the Heideggerian “détour

ontologique” but, instead of focusing on the “différence” (Unterschied), Ricoeur prefers to “defer” the ontological once again