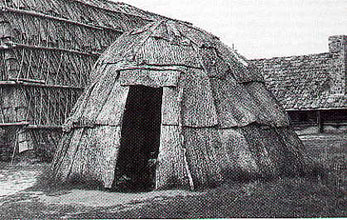

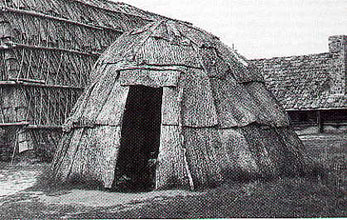

Unlike the Plains Indians, who could dismantle their dwellings and take their housing with them, the Shawnee built permanent structures that had to be left behind. It might be expected that a people who moved as often as the Shawnee would adopt movable houses similar to the teepee used by the Indians on the Western Plains. But conditions in the Eastern Woodlands differed from those in the Plains in several respects. Unlike the Plains, the Woodlands offered an abundant supply of materials for houses, a circumstance making it unnecessary to transport such materials from place to place. And it would have been impossible to drag a travois over the woodland trails, even if the Shawnee had used dogs or horses for this purpose. Therefore it was more practical for the Shawnee to abandon their homes and build new ones at their new location Shawnee houses were single-family dwellings, easily constructed in a few days and abandoned with little concern. The Shawnee wigwam or wegiwa was square or oblong in shape, and the dimensions were determined by the size of the family. The construction of the wegiwa has been most thoroughly described by Thomas Wildcat Alford in his book "Civilization":

In building a wegiwa the bark was obtained by first severing it from the body of a tree as it stood, mostly from elm and birch....the bark was laid flat on level ground, with flesh side under, weighted down with small logs, and allowed to dry to a certain extent, but used while still soft and pliable. Then poles were cut of straight young trees and set into the ground at regular distances apart, outlining the size desired for the wegiwa. All bark was peeled off the poles to keep worms from working in it. Two of these poles with a fork at the top of each were set at opposite ends and at half way the length of the wegiwa. Upon these forks were laid the ends of a long pole...tied securely with rough bark. This formed the top comb of the roof, to which the rest of the poles were bent to a suitable height for the walls and firmly secured there with strips of bark. Then upon and across these were laid other poles at regular distances from the top comb, down the slope to the end of the roof, and on down the sides to form the walls. Upon these cross poles were laid the sheets of bark...securely held in place by other poles laid on the outside of the bark and tied fast to the poles within. The work seems intricate...but to a dexterous Indian woman...it was easily and quickly done.

Sometimes platform beds, tables, shelves, and benches were constructed inside the wegiwa. The structures were waterproof and provided a comfortable dwelling even in the cold weather. Since the bark could be easily removed only in the spring, hides of animals were often substituted in houses constucted at other times of the year.

Besides individual homes, the larger and more permanent Shawnee villages also contained a council house called a msikamekwi. These were much larger structures, used for ceremonies and secular dances in addition to council meetings. The explorer Christopher Gist described the "statehouse" at Lower Shawnee Town at the mouth of the Scioto River as being about ninety feet long. The council house at Greenville, Ohio was a frame structure 150 feet by 34 feet in size. The building formed the nucleus of the community and was constructed cooperatively by the entire village.

Shawnee migration from place to place was carried out in an efficient and orderly manner. The organization was determined in part by the size of the group, and the size was a function of the availability of food. When food was scarce, large groups split into small family groups while traveling, to make better use of food sources. A strict sexual division of labor was observed, and the line of march was a rank in single file with the women bringing up the rear. The men carried only their arms and bedroll and were responsible for supplying the meat along the journey. All movable inventory that was transported from one location to another was carried by the women. Thus they carried little with them preferring instead to remake what they needed at their new site.

The pace of travel was slow as the Shawnee were never in a hurry. Before breaking camp and beginning a day's march they would eat a hearty meal and mend clothing. Once they started they seldom stopped until sunset, but they rarely traveled more than a few miles a day. if a family group killed a bear or other large animal they would stay in camp until it was consumed rather than carry it along. Often relocation involved a prolonged journey. The Shawnee might camp in one locality for weeks, or even months, waiting for floods to subside or taking advantage of favorable hunting conditions. Sometimes a crop of corn was planted and harvested before the journey was resumed.

Meat was the main sustenance while traveling, supplemented by corn flour eaten raw or used as a thickening for stew. Little effort was made to provide for other biological needs. Unless a camp stayed in one locale for a while, no shelters were built. The one exception was the construction of sweat houses in which travelers soothed their tired muscles.

Although most Shawnee villages were along navigable streams, most of the travel was overland by foot. Wagons or travois were not used, and horses were not employed until relatively late. Rivers were crossed by wading, even in the winter. If the river was too deep to ford, the Shawnee would build rafts of logs tied together with vines or bark. Narrow streams might be crossed by felling a tree and walking across the trunk.

The Shawnee used the many paths that honeycombed the Eastern Woodlands. The complex network of trails and paths was remarkable in it adaptability to changing seasons and conditions of travel. Most Indian paths managed to keep nearly a direct course. The principals of trail locations were that the paths be dry, level, and direct. But the basic necessities of water, food, and clothing led the Indians to springs, salt licks, and other places where these could be obtained. On level terrain, animal trails often provided the most direct route to locations best supplying man's necessities. In the mountains or hills, trails often led along the higher ground and ridges. These ridge paths were more level than the mountain spines, were above the flood plain, and were well drained. Hilltops were windswept of snow in the winter and of brush and leaves in the summer. River trails were not extensively used by the Shawnee. The winding rivers were seldom a direct route, and large rivers, such as the Ohio, had steep slopes, cut by deep ravines, making travel along them impossible.

Since the only routes in the western wilderness were these unmarked trails, the Cumberland region and the Ohio Valley remained free of white settlers for a long time. Wagons had to stop at the mountains, and the uncharted rivers were hazardous.

© 1997 shawnee_1@yahoo.com