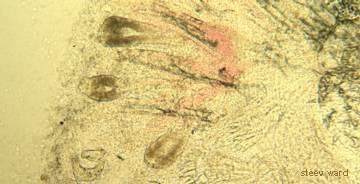

This is typical appearance for a gill fluke such as Dactylogyrus vastator at about 0.2 mm length. Note the four pigment spots on the four-lobed anterior. Hooks are not especially prominent on this specimen.

Phylum: Platyhelminthes

Class: Monogenea

Previously these were listed in the class Trematoda and are often still referred to as monogenetic trematodes. Commonly we refer to monogenetic and digenetic flukes (the Digenea still considered in the class Trematoda), and divide the monogeneans into skin flukes and gill flukes. Gill flukes are sometimes called “ Dactyls” for short. While Dactylogyrus vastator is the most well-known of the gill flukes there are several other genera and many species involved. Here I will refer to them simply as Gill Flukes. To add a bit to the confusion there are some flukes of the Digenea that sometimes are found encysted in the gills of fish. I will refer to those separately.

Large view of Dactylogyrus from a Silver Dollar (Metynnis sp.).