Hardware.

Shielded and Unshielded Twisted Pair.

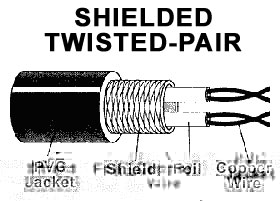

Twisted pair is the ordinary copper wire that connects home and many business computers to the telephone company. To reduce crosstalk or electromagnetic induction between pairs of wires, two insulated copper wires are twisted around each other. Each connection on twisted pair requires both wires. Since some telephone sets or desktop locations require multiple connections, twisted pair is sometimes installed in two or more pairs, all within a single cable. For some business locations, twisted pair is enclosed in a shield that functions as a ground. This is known as shielded twisted pair (STP). Ordinary wire to the home is unshielded twisted pair (UTP).

Twisted pair is now frequently installed with two pairs to the home, with the extra pair making it possible for you to add another line (perhaps for modem use) when you need it.

Twisted pair comes with each pair uniquely color coded when it is packaged in multiple pairs. Different uses such as analog, digital, and Ethernet require different pair multiples.

Although twisted pair is often associated with home use, a higher grade of twisted pair is often used for horizontal wiring in LAN installations because it is less expensive than coaxial cable.

The wire you buy at a local hardware store for extensions from your phone or computer modem to a wall jack is not twisted pair. It is a side-by-side wire known as silver satin. The wall jack can have as many five kinds of hole arrangements or pinout, depending on the kinds of wire the installation expects will be plugged in (for example, digital, analog, or LAN). (That's why you may sometimes find when you carry your notebook computer to another location that the wall jack connections won't match your plug.)

Diagram of Twisted Pair Cable

Diagram of Twisted Pair Cable Configurations

Coaxial Cable.

Coaxial cable is the kind of copper cable used by cable TV companies between the community antenna and user homes and businesses. Coaxial cable is sometimes used by telephone companies from their central office to the telephone poles near users. It is also widely installed for use in business and corporation Ethernet and other types of local area network.

Coaxial cable is called "coaxial" because it includes one physical channel that carries the signal surrounded (after a layer of insulation) by another concentric physical channel, both running along the same axis. The outer channel serves as a ground. Many of these cables or pairs of coaxial tubes can be placed in a single outer sheathing and, with repeaters, can carry information for a great distance.

Coaxial cable was invented in 1929 and first used commercially in 1941. AT&T established its first cross-continental coaxial transmission system in 1940. Depending on the carrier technology used and other factors, twisted pair copper wire and optical fiber are alternatives to coaxial cable.

Fiber Optics.

Fiber optic cable for

10BASE-FL

Fiber-Optic Inter-repeater Link

(FOIRL) networks

Hubs.

In general, a hub is the central part of a wheel where the spokes come together. The term is familiar to frequent fliers who travel through airport "hubs" to make connecting flights from one point to another. In data communications, a hub is a place of convergence where data arrives from one or more directions and is forwarded out in one or more other directions. A hub usually includes a switch of some kind. (And a product that is called a "switch" could usually be considered a hub as well.) The distinction seems to be that the hub is the place where data comes together and the switch is what determines how and where data is forwarded from the place where data comes together. Regarded in its switching aspects, a hub can also include a router.

In describing network topologies, a hub topology consists of a backbone (main circuit) to which a number of outgoing lines can be attached (dropped), each providing one or more connection port for device to attach to. For Internet users not connected to a local area network, this is the general topology used by your access provider. Other common network topologies are the bus network and the ring network. (Either of these could possibly feed into a hub network, using a bridge.)

As a network product, a hub may include a group of modem cards for dial-in users, a gateway card for connections to a local area network (for example, an Ethernet or a token ring), and a connection to a line (the main line in this example).

Switch.

In telecommunications and network, a switch is a network device that selects a path or circuit for sending a unit of data to its next destination. A switch may also include the function of the router, a device or program that can determine the route and specifically what adjacent network point the data should be sent to. In general, a switch is a simpler and faster mechanism than a router, which requires knowledge about the network and how to determine the route.

Relative to the layered Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) communication model, a switch is usually associated with layer 2, the Data-Link Layer. However, some newer switches also perform the routing functions of layer 3, the Network Layer. Layer 3 switches are also sometimes called IP switches.

On larger networks, the trip from one switch point to another in the network is called a hop. The time a switch takes to figure out where to forward a data unit is called its latency. The price paid for having the flexibility that switches provide in a network is this latency. Switches are found at the backbone and gateway levels of a network where one network connects with another and at the subnetwork level where data is being forwarded close to its destination or origin. The former are often known as core switches and the latter as desktop switches.

In the simplest networks, a switch is not required for messages that are sent and received within the network. For example, a local area network may be organized in a token ring or bus arrangement in which each possible destination inspects each message and reads any message with its address.

Most data today is sent, using digital signals, over networks that use packet-switching. Using packet-switching, all network users can share the same paths at the same time and the particular route a data unit travels can be varied as conditions change. In packet-switching, a message is divided into packets, which are units of a certain number of bytes. The network addresses of the sender and of the destination are added to the packet. Each network point looks at the packet to see where to send it next. Packets in the same message may travel different routes and may not arrive in the same order that they were sent. At the destination, the packets in a message are collected and reassembled into the original message.