Western Civilization I

Notes from 6/26

|

Social division, primarily among grandis and popolo grosso, within the city-states produced constant conflict. Over time, powerful political leaders, known as despots rose up to maintain order. Perhaps the best know despot was Cosimo de Medici (1389-1464), a wealthy Florentine banker who guided Florence from behind the scenes. The ideals of Renaissance despotism were later articulated by Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527). Impressed with the way Roman rulers had governed the Empire, he urged despots like the Medicis to be absolutely ruthless.

As despots accumulated wealth and power, they and other prominent families became patrons of the arts, financing the cultural revival that became known as the Italian Renaissance. Besides the development of this wealthy patron class, the middle class or bourgeoisie played an important role in the development of Renaissance thought. The bourgeoisie began to feel that medieval education (known as Scholasticism) did not provide the practical training needed by the increasingly literate lay population. Scholasticism was well-suited to train Christian theologians, but merchants and guild masters wanted more practical skills, such as good speaking and writing. Increasingly, teachers of rhetoric in Italy began to turn back to Greco-Roman classics (like Plato's Republic) for models of good speaking and writing, and rhetoricians argued, starting in the late 13th century, that educators should pay more attention to these "lost" classics.

The most influential of these thinkers, to whom we now refer as humanists, was Francesco Petrarca, better known as Petrarch (1304-1374). Petrarch viewed his contemporaries as too worldly and materialistic, and felt that the early Church fathers and ancient Romans were more worthy examples of the "moral life." Petrarch believed that mastery of the written and spoken word had distinguished the Romans, and that by imitating their style his contemporaries could learn to behave like the ancients. This idealization (without critical inquiry or questioning) of the Greco-Roman past typifies the outlook of the Italian Renaissance.

Humanism's campaign for a return to the classics started a revolution in Florence, which soon spread throughout Italy. The crusade to study and imitate ancient Greco-Roman civilization transformed art, literature and even (eventually) political and social values.

I discussed a number of Renaissance artists to illustrate the new emphasis on the Greco-Roman past. These include Masaccio (1401-1428), whose emphasis on nature and three-dimensional human bodies departed from medieval form. Masaccio's painting, The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (1426) depicted some of the first nudes since antiquity. Likewise, the sculptor Donatello (1386-1466) embraced the Greco-Roman emphasis on the beauty of the human form, in sharp departure from medieval Christianity's asceticism. And the architect Brunelleschi (1377-1446) imitated Roman forms in his cathedrals and public buildings. The ambitious nature of Brunelleschi's cupola (dome) of the Cathedral Santa Maria del Fiore reflected the Renaissance's new emphasis on human ingenuity and potential.

|

The artists at work in the early years of the 1500's are often referred to as the generation of the High Renaissance in Italy. Four artists in particular -- Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Titian -- represent the pinnacle of the humanist revival in art.

Leonardo da Vinci's (1452-1519) anatomical drawings illustrated Renaissance man's new interest in science, and his technical drawings represent a departure from the medieval view that limited man's potential to innovate and alter his environment. Finally, Leonardo's drawings and paintings demonstrated a new awareness of, and sensitivity to, the beauty of the human form, characteristic of the High Renaissance and in sharp contrast to the medieval view that the body must be renounced for the sake of the soul's salvation.

Raphael's (1483-1520) most famous work, The School of Athens (1509) expressly celebrates the ancient Greeks. But as I pointed out in class, his ancient philosophers are given the faces of contemporary Renaissance men. Plato is played by Leonardo da Vinci, and Heracleitus is portrayed by Michelangelo. Hence Raphael makes the statement through his art that the Renaissance is a continuation of the ancient past, rediscovered after centuries of neglect.

|

|

|

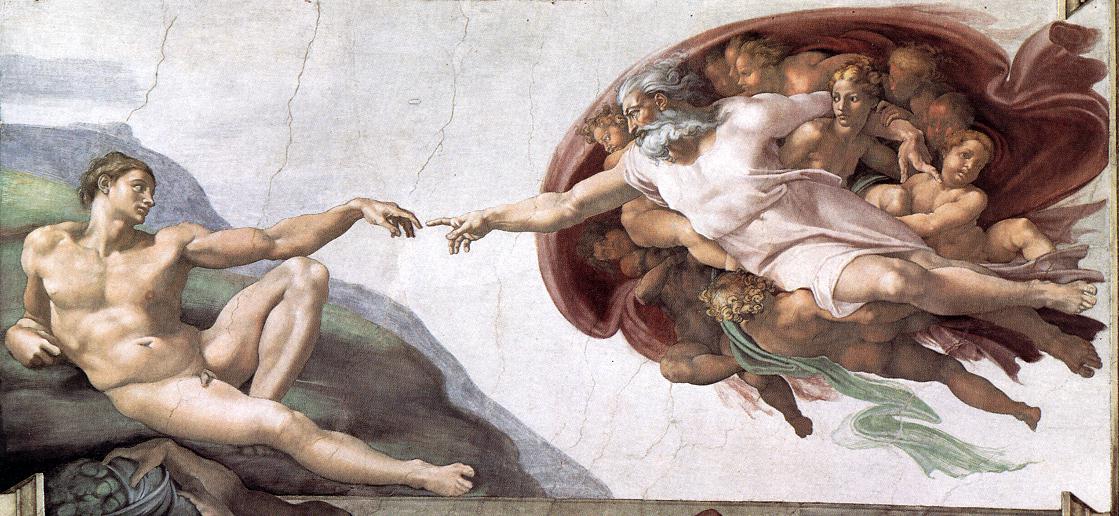

Along with Leonardo, Michelangelo (1475-1564) is perhaps the greatest name of the Italian Renaissance. No other artist so clearly captured the Renaissance's spirit and embrace of Greco-Roman forms. In the famous Creation of Adam (1510), Michelangelo's God is an anthropomorphic Zeus, and the muscular Adam reminiscent of a Greek Apollo or Prometheus. This blending of the pagan past with Christian themes is characteristic of the High Renaissance (and was not without controversy at the time). Similarly, Michelangelo's famous statue of the Old Testament's David (c. 1504) is not merely an imitation of the Greek kouros; in form and technique he may have actually surpassed the ancients.

|

|

Starting in the late 15th century, French, Spanish and German monarchs grew covetous of the Italian city-states' wealth, and began to invade the Italian peninsula. In 1527, Rome itself was sacked, and Italy entered into a long period of political instability and cultural decline. But by then, the humanist ideals of the Italian Renaissance had spread north, to France and Germany. A second, critical phase of the Renaissance had begun, which we will discuss tomorrow.