Batrcop.com> RFK Assassination Page> The AssasinationThe Assassination

June 4, 1968, was an important but nerve-wracking day for Robert Francis Kennedy, senator from New York. . A week earlier he had lost a vital race for West Coast votes in the state of Oregon to Senator Eugene McCarthy in the Democratic Primary, dampening the spirit of the Kennedy campaign. But, now, here in California, his supporters foresaw good things to come. With its 174 delegates as the prize, California was a very strategic ballot box for any one of the nominees to walk away with, and, best for RFK, it was believed to be a "Kennedy state". Taking a California victory into the Democratic Convention in Chicago would be powerful. And it was really no secret that the Democratic Party itself preferred Kennedy to win, for if anyone could beat Republican Richard M. Nixon in the upcoming Presidential run it would be a Kennedy. That had been proven in 1960.

Senator Robert Kennedy and wife Ethel at the California Victory celebration

(Assassination Archives and Research Center, D.C.)

With the ballot boxes having closed at sunset, and the California networks updating returns throughout the evening, nearly 2,000 campaign workers crowded the Embassy Ballroom, of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles; the mood was festive and the hopes high. As the evening progressed, and the monitors showed RFK’s numbers taking the lead, his supporters on site went wild and started chanting for him. They wanted a speech. They knew he was upstairs and they were waiting for that delicious moment when he would join the party, flick on the podium microphones and officially announce what they expected all day – a Kennedy Victory!

Meanwhile, RFK remained watchful, cautious, glued to his television in the Royal Suite where good friends, political allies and a few celebrities encircled him. Football great Roosevelt "Rosey" Grier was there, and so was Decatholon champ Rafer Johnson. Occasionally, Kennedy leaned over to joke with one of these men or to seek advice from one of his aides and advisors – Pierre Salinger, Ted Sorenson or press secretary Fred Mankiewicz, for example – for an impromptu consultation. Wife Ethel, in her early pregnancy with their eleventh child, relaxed on the sofa near her husband.

Kennedy was tired. Despite his love for a good campaign brawl, he had earlier in the day considered remaining physically out of the limelight for the evening. He would have preferred that the media cover his part of the campaign from the home of movie director John Frankenheimer, where he and Ethel were staying. But, all the TV stations refused to move their equipment away from the central action, which meant that if he wanted coverage he would have to appear at his campaign headquarters.

By 11:30 p.m., a victory for Kennedy seemed imminent. With wife Ethel and his entourage, the senator moved to the ballroom where, upon entering, was greeted by frantic applause. Red-white-and-blue ribbons decorated the wall behind the speaker’s podium and balloons colored the ceiling overhead, flashbulbs popped, and music from an orchestra sent the sea of heads before the stage bobbing in rhythm. Raising his arms for attention, a smiling "Bobby," as his fans called him, thanked the room for their great support and, adding a bit of humor, thanked pitcher Don Drysdale for winning his sixth straight shut-out that afternoon.

Then the speech turned serious. Kennedy addressed the fact that the nation needed to overcome racial divisions and other social evils (the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King had taken place exactly two months ago to the day), as well as an end to the unpopular war in Vietnam. Concluding his speech with a victory sign and the words, "…now on to Chicago, and let’s win there!" the house once again broke loose. "We want Bobby! We want Bobby!" sang the house. Grinning, he turned towards the side door that would take him through a food preparation area, a short cut to where the press was waiting in the Colonial Room beyond. It was now 12:15 a.m., June 5.

Odd as it seems, no formal security measurements were in effect during the event, despite the fact that a major political figure was exposed to some 2,000 people in the course of an evening. "The Secret Service was not there," William Klaber and Philip Melanson tell us in their investigative Shadow Play. "They would protect presidential candidates only after the events of the night. Also absent were the Los Angeles police."

Instead, only hotel security and a few hired guards from Ace Security, a local protection firm, protected the Kennedy group.

Bill Barry, an ex-FBI man, helped Ethel off the platform, but in doing so, fell steps behind the entourage. Because of the mass of onlookers who flushed forward and now separated him from the senator and his party, Barry found it impossible to catch up where he would have liked to have been, ahead of the main figure and not several feet behind him.

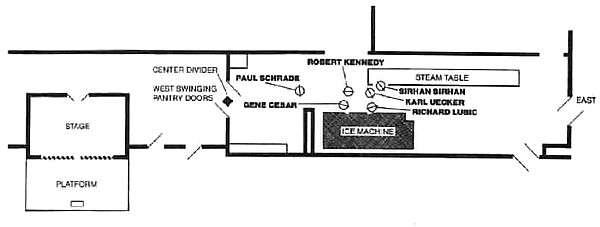

Crime scene diagram

(LAPD)

Just outside the kitchen, 26-year-old Ace Security guard Thane Eugene Cesar took the senator’s right elbow and led him through the swinging doors. Inside, busboys and waiters craned their necks to catch a glimpse of the possible next President of the United States. The aisle Kennedy traversed was narrow, sided by steam tables, cart trays and dish conveyor belts. Media had already taken up some of the access area and Maitre’d Karl Uecker, leading the parade, found the pathway clogged and the route slow going. Klaber and Melanson estimate that there were some 77 people in that small diameter at the time and compared the situation to stuffing that number of people into a subway car.

If Senator Kennedy spotted the small, swarthy young man approach him at all, he would have figured he was just one of the many hotel personnel who wanted to shake his hand or beg an autograph. But as this comer neared, he leveled a gun in Kennedy’s direction and opened fire.

At that moment, history blurred. A .22 caliber pistol flashed and Kennedy seemed to waver sideways. Some in the room froze at the sound, but others, recognizing it, dodged and ducked. The gun barked again, and in that instant, speechwriter Paul Schrade spun to the ground, hit in the forehead. By this time, maitre’d Uecker had been able to catch the shooter’s gun arm and press it down on the steam table beside him. Nevertheless, the gun continued to explode, a third time, a fourth time, and more, its barrel aiming straight into the procession. Rosey Grier, Rafer Johnson and others struggled to disarm the assailant and corral him. But, in the 40 seconds it took to pry the gun loose, all eight cylinders of the weapon emptied. Kennedy sprawled on the floor, spread-eagled and in pain. Behind him, Schrade writhed. Seven-year-old Irwin Stroll was clipped in the kneecap; ABC-TV director William Weisel grabbed his stomach where a bullet had entered; reporter Ira Goldstein’s hip had been shattered; and an artist friend, Elizabeth Evans was unconscious from a head wound. Confusion and horror gripped the onlookers, some of them speechless, numbed.

Senator Kennedy mortally wounded with rosary in hands .

(UPI/Corbis/Bettmann)

"Come on, Mr. Kennedy, you can make it," pleaded busboy Juan Romero, who pressed a pair of rosary beads in the senator’s upward palm. He bent down to hear the victim’s barely audible voice asking, "Is everybody all right?" The first doctor on the scene was Stanley Abo. He gently moved in between Kennedy and his weeping wife. Kennedy’s breathing was sparse. Groping to find a wound, he discovered a hole behind the head, below the right ear. The doctor’s finger prodded the wound to open the coagulation and allow free passage of blood. The senator’s breathing became more regular. "You’re doing good, sir," the doctor comforted him, then signaled someone to call an ambulance.

Meanwhile, police appeared; two rookies, Arthur Placencia and Travis White. They gasped when entering the pantry, never before having seen anything like this massacre. Writer George Plimpton had been one of the men who had taken the gunman down; he told the police that the assailant seemed not quite aware of what was going on; even during the struggle with his captors, the man had, what he termed, "peaceful eyes". Still embracing the gunner in an armlock, huge Jesse Unruh of the California State Assembly, turned him over to the pair of cops. "I charge this man in your responsibility," he said, and followed them and their prisoner to the squad car curbed outside the hotel. Along the way, they encountered angry citizens shouting threats to the man in their possession.

Sirhan Sirhan in custody

(UPI/Corbis/Betmann)

When a series of ambulances arrived, attendants placed the injured, including Kennedy, on stretchers and rushed them to Central Receiving Hospital eighteen blocks away. Ethel accompanied her husband in the emergency van, as did some of his closest aides. At Central Receiving, doctors found the wound behind the ear and powder burns around it, which indicated that the shot that struck him was fired at an extremely close range. Not having a neurosurgeon on site, the administration rushed him to Good Samaritan Hospital where he would be better attended. It was now 1 a.m.

Doctors at Good Samaritan uncovered two more wounds on Kennedy – one in the right armpit and another several inches down. It wasn’t long after that press secretary Fred Mankiewicz appeared out front the hospital to tell a curious press that Kennedy was about to undergo an operation. His condition? "Critical," Mankiewicz answered somberly

The operation took three hours. Surgeons removed a blood clot that had re-formed behind the brain, and as many "fragments of metal and bone as they could," Melanson and Klaber state. "The senator could now breathe unassisted (but) suffered an impairment of blood to the mid-brain." Afterwards, the patient was placed in critical care with round-the clock supervision. The next 12 to 36 hours were crucial, they reported.By noon, RFK’s brain waves read below normal on the electroencephelograph; by 5 p.m., his condition was "extremely critical". Crowds collected outside, between the hospital and a press center set up in an auditorium across the street. Darkness and a chill notwithstanding, public vigil remained steadfast long after midnight.

At 2 a.m., June 6, the crowd spotted Mankiewicz leaving the hospital, looking rather stolid, heading for the makeshift press room. It hushed. Then came the announcement they dreaded: "Senator Robert Francis Kennedy," Mankiewicz’s voice cut the airwaves, "died at 1:44 a.m. today…He was 42 years old."

The nation mourned. And it was bitter. A Gallup Poll showed that Americans believed "by a margin of 4 to 3 that the attack was a product of a conspiracy."

Batrcop.com> RFK Assassination Page> The Assasination