|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Catholic Struggle in |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

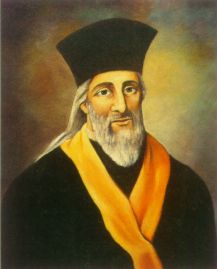

The Catholic Church began to make itself felt in Vietnam during the declining days of the Latter Le Dynasty, a dynasty under which, in previous years, Vietnam had reached its height of wealth and power. One of the missionaries who went to Vietnam, and had a greater impact than any other, which is still felt today; was Father Alexander de Rhodes of the Society of Jesus. In 1620 he joined the Jesuit mission in Hanoi, the capitol city of the Le Emperor. However, by this time, the Le Emperor held only nominal power. Actual authority in northern Vietnam was held by the Trinh family. Father Rhodes did incredible work during his time there. He wrote a Vietnamese catechism, converted roughly 6,000 Vietnamese himself and developed a Latin alphabet for the Vietnamese language to aid in translating. This written form of Vietnamese, which replaced the more complicated style based on Chinese writing, is still the official form of written Vietnamese today. He traveled and worked throughout northern Vietnam, strengthening the Catholic presence to such a degree that it alarmed the Trinh overlord Trinh Trang who therefore exiled Rhodes in 1630. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fr. Alexandre du Rhodes |

|

|

|

|

|

| Father Rhodes did not abandon Vietnam though. He eventually returned, but to south Vietnam which was ruled by the Nguyen family. He did his same good work there building churches and converting Vietnamese and in the same way alarmed the local potentate Nguyen Phuc Lan who actually ordered Father Rhodes to be put to death. However, the sentence was not carried out and Father Rhodes was exiled again, this time under threat of execution should he ever return. He went to Rome and continued to push for more missionary work in Vietnam and more aid to be sent to the always endangered population of Vietnamese Catholics. Life would not be easy for the Vietnamese faithful, but the groundwork had been laid and more progress was to be made in the future and ultimately Catholics were to play an essential role in the ongoing feud between the Nguyen and the Trinh families for control of Vietnam. |

|

|

|

|

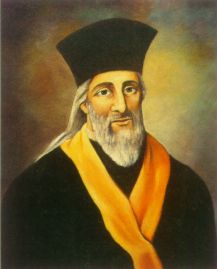

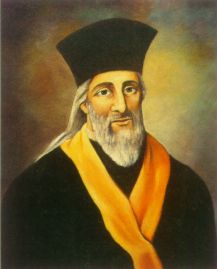

| Officially, both sides condemned Christianity but both sides needed every man they could find to continue fighting their wars. Eventually the people became sick of the constant wars and heavy taxation on the part of both the Trinh and Nguyen and so rallied in 1771 to three brothers who led the Tay Son rebellion. They defeated the Trinh, almost exterminated the Nguyen family and by 1788 had won total control of Vietnam. Then, in a surprise move, they overthrew the Le Emperor and one of the brothers, Nguyen Nhac, became Emperor Thai Duc. Meanwhile, in the south, the sole surviving heir of the Nguyen family, Nguyen Phuc Anh, was forced to flee for his life and he found refuge on Phu Quoc Island in 1777 thanks to another Catholic who was to have great influence on Vietnamese history, Monsignor Pierre Pigneau de Behaine, later the Bishop of Adran. |

|

|

|

|

|

Bishop Pierre de Behaine |

|

|

| Behaine and his missionaries took Anh in, sheltered him and Behaine even became his champion in the court of the King of France. Anh would never forget his friendship with Behaine and the physical salvation at least which the Catholics gave him. Anh promised that if the French and the Catholics would help him, he would allow freedom of worship and the conversion of any to Christianity who desired it. Behaine saw a golden opportunity and urged the French government to help Anh in his goal of overthrowing the Tay Son and uniting Vietnam under his rule. However, at this same time, perhaps as a result of this, the Tay Son regime began a brutal persecution of Catholics. The ruler, Emperor Canh Thinh, on August 17, 1798, issued an edict ordering the destruction of all Catholic churches and seminaries and effectively declaring war on the Christian religion in Vietnam. Naturally, this did even more to drive Catholics into the arms of the Nguyen and Prince Anh. |

|

|

|

|

The persecution was savage and more than 100,000 Catholics were martyred, but God had not forgotten his people in Vietnam as evidenced by an appearance by the Blessed Virgin Mary. The area around the town of Quang Tri was used as a place of refuge by many Vietnamese Catholics. Many were sick, hungry, some were wounded and they hid in the jungle to pray and prepare their souls for the ultimate sacrifice of martyrdom. Then, Our Lady appeared to them one night as they gathered around the fire saying the rosary. She was flanked by two angels and held the Divine Child in her arms as she comforted them, even telling them how to make medicine and promised that henceforth, any who came to that spot to pray would have their prayers answered. Ultimately, this place, La Vang, would have a church built on it and become the most prominent place of pilgrimage in all of Vietnam. |

|

|

|

Our Lady of Lavang |

|

|

| Ultimately, Anh rebuilt the Nguyen forces and with the help of French forces and more modern equipment provided with the help of Bishop Behaine as well as the support of the Catholic Vietnamese, a full scale war was launched against the fractured Tay Son regime. Anh was eager for French support and sent his son and heir, Crown Prince Canh, to France along with Behaine as a show of goodwill in the hope of persuading King Louis XVI to agree to an alliance, which the King finally did. Prince Canh signed on behalf of his father and while in Europe was given a modern education and converted to Catholicism. He returned with Bishop Behaine to fight alongside his father and hope seemed bright for the Catholic community with Lord Anh promising freedom of religion set to take power and his eldest son already a Catholic in addition to the hopeful message of Our Lady of Lavang. |

|

|

| Indeed, the war was a successful one, though a sad blow was struck when Crown Prince Canh died of smallpox while fighting at Qui Nhon at the age of 19. Bishop Behaine was with his army as was the great Nguyen general Le Van Duyet who succeeded in capturing the city and crushing the Tay Son forces. Behaine himself died of dysentery during the battle as well. The Nguyen forces, however, were triumphant and marched on to take Hanoi and unite all of Vietnam under their rule in 1802 when Anh declared himself Emperor Gia Long of the newly established Nguyen Dynasty. Little did he know that his was to be the last imperial dynasty Vietnam would ever have. Emperor Gia Long showed no mercy to his enemies but great favor to his friends, particularly the French soldiers who had helped him gain the throne. For Bishop Behaine he held a lavish funeral service the likes of which had never been seen in Vietnam before and would never be seen again. True to his word he also allowed religious freedom, tolerated Christianity and recognized a special place for France in his foreign relations. Yet, hard times were still ahead. |

|

|

| During the later half of the reign of Emperor Gia Long there was a slight division in the court between those who gravitated toward the traditional strength of China and those who gravitated toward the new and advanced power of France. Following the death of Crown Prince Canh, the heir to the throne Prince Nguyen Phuc Dam became the leader of the pro-Chinese faction. He was distrustful of any foreign presence in Vietnam and believed in strict adherence to the Confucian values and social hierarchy. In 1820, when he ascended the Golden Throne as Emperor Minh Mang, he was able to put his vision of Vietnam into practice, which differed from that of his father mainly in opposition to innovation and opposing Christianity. |

|

|

| Almost at once Minh Mang faced considerable opposition. Part of this came from grass roots resistance to the rule of the mandarins and the strict structures and legal codes adopted throughout the country, most of which were copied verbatim from the Chinese Empire. However, the most dangerous and prominent opposition leader was Le Van Duyet. He had been one of the top subordinates of Emperor Gia Long during the war which brought the Nguyen to power and was considered a national hero by many throughout Vietnam. He had captured Qui Nhon alongside the Catholic Crown Prince Canh and he viewed the persecutions of Christians enacted by Minh Mang to be a betrayal of the brave Catholics who had taken in his father when he was hunted and persecuted and who fought for him in his battle to take the throne and reunite Vietnam. |

|

|

| Many in the country were outraged when, following the death of Le Van Duyet, Emperor Minh Mang had his grave violated and desecrated his body in public in 1832. Naturally this made his son, Le Van Khoi, a committed enemy of Minh Mang. Calling upon the peasants who were tired of the mandarins and heavy taxes and the Christians who were being persecuted, Le Van Khoi launched a massive rebellion against Emperor Minh Mang. Many people were also swayed by the personal trauma of Le Van Khoi and sympathized for him and the way the memory of his father had been so brutally assaulted. It seemed to all those involved like a righteous crusade. It was also seen as an opportunity for the Kingdom of Thailand. Siamese troops stormed across the border at this moment ready to strike a blow in the long running conflict between Thailand and Vietnam over the Lao and Cambodian frontier. The Nguyen Imperial army was stretched almost to the breaking point by this combination of outside invasion and internal rebellion. However, ultimately the forces of the Emperor prevailed, albeit barely, and once both enemies were dealt with a savage campaign of reprisals was carried out throughout the country. |

|

|

|

|

| Emperor Minh Mang, a strict adherent of Confucianism and nothing else, became even more entrenched in his opinions of anything foreign or contrary to the Confucian order. Especially since the rebellion in which so many Catholics had taken part, he was adamant in his condemnation of Christianity saying, "The perverse religion of the Europeans corrupts the hearts of men". All contact with foreign nations was cut off, the French officials employed by his father were dismissed and many Christians were martyred including Vietnamese Catholics like St Andrew Dung Lac, St Peter Thi and St Joseph Canh. This campaign continued during the reign of Emperor Thieu Tri, who succeeded Minh Mang on the Golden Throne in 1841. Among the disaffected peasants, Le dynasty loyalists and those brutalized by corrupt mandarins, the Catholics were singled out as the source of unrest for the Nguyen Emperor. In 1847 a French naval squadron demanded that Thieu Tri release those imprisoned simply for being Catholic and to allow religious tolerance. When he refused the French ships attacked the coastal city of Danang. Enraged by the attack, Thieu Tri ordered all Christians in Vietnam to be massacred but he died a short time later before this genocidal policy could be put into effect. |

|

|

|

| St Andrew Dung Lac |

|

|

|

|

|

| During the reign of Thieu Tri and his persecution of the Church, another Vietnamese Catholic who was to become quite famous had to flee the country. This was Nguyen Truong To. French missionaries took him to safety and he was educated in France and Malacca, even going to Rome to meet the Pope, before being able to return to his homeland. In Vietnam, although spared the fulfillment of the last order of Thieu Tri, conditions did not improve for the Catholics of Vietnam. Thieu Tri had left the throne to his younger son who became Emperor Tu Duc, who would be the longest reigning Emperor of the Nguyen Dynasty. Tu Duc was, like his father and grandfather, a strict adherent of Confucianism, distrustful of outsiders, opposed to innovation of any kind and intolerant of Christianity. He was also opposed by his older brother who had been passed over for the throne, Crown Prince Hong Bao. |

|

|

| Peasant uprisings had been commonplace since the Nguyen reign began and now, in the person of Crown Prince Hong Bao, all of the disaffected groups had reason to hope. Oppressed peasants, Le dynasty loyalists and persecuted Catholics rose up again in another rebellion. Knowing the attitudes of Tu Duc, the priests were convinced that Crown Prince Hong Bao would be more favorable to their cause. Once again, however, the Nguyen forces were victorious and Emperor Tu Duc had his brother thrown in prison after his mother prevailed upon him not to have him executed. Nonetheless the unfortunate Crown Prince committed suicide in prison shortly thereafter; according to the official histories anyway. Nonetheless, this initial challenge to his authority only made Tu Duc more ill disposed towards the Catholic community which was already the most common scapegoat for opposition to the regime. Emperor Tu Duc unleashed a savage persecution of Christians, having thousands massacred and calling Christianity, like his grandfather did, a perverse doctrine that was poisoning the country. This was mostly due to the fact that the Church taught that all people are sinners and in need of the salvation of Christ whereas in the Confucian belief, the Emperor was the Son of Heaven and therefore had no need of a personal savior. Likewise there could be no room for the Pope in this strict brand of Confucian orthodoxy as it was the Emperor who was supreme on earth and acted as pontiff to the heavens. |

|

|

|

|

|

| This new campaign of persecutions soon brought down the wrath of the French on Vietnam. Emperor Napoleon III was now ruling France and his devoutly Catholic wife, the Empress Eugenie, was always quick to come to the defense of the Church wherever she was threatened. When French forces began to arrive in Vietnam the Nguyen troops proved to be no match for them. This was a direct result of the hermit policies of Tu Duc and his predecessors. Obsessed with strict adherence to Confucian doctrine the country became intellectually stagnant. All innovations were forbidden and developments in the outside world went unnoticed thanks to the strict policy of isolation. Naturally, some of the imperial mandarins saw the foolishness of this attitude, one of which was the Catholic Nguyen Truong To. He had won a lowly place at the court of Tu Duc thanks to the help of another mandarin and Nguyen Truong To urged the Emperor and his court to modernize the country study the advances of other nations and embrace progress rather than stagnation. He wrote tirelessly to the Emperor on his ideas and suggestions, but after considerable debate the dogmatic mandarins prevailed and Tu Duc continued his policy of isolation, confident in his own Confucian moral superiority. |

|

|

|

Empress Eugenie of France |

|

|

|

|

| The result was the swift victory of French forces over the Nguyen army. In 1861 the French captured Saigon and when another massive internal rebellion broke out in northern Vietnam, with considerable Catholic support, in Bac Bo. Emperor Tu Duc had to divert his forces to suppressing this challenge to his authority which was judged more dangerous than the French occupation of the south. He also called for help from his nominal overlord the Emperor of China, but the French were able to defeat the Chinese as well and Emperor Tu Duc was forced to come to terms with France and recognize their ownership of the south and protectorate over the north. The Vietnamese Catholics did not abandon their sense of patriotism, and there was no mass uprising in cooperation with French forces. However, with the increasing presence of the French it would mean greater religious freedom for Christians, but not before at least one last trial by fire. |

|

|

|

| Following the death of Tu Duc, who had no children despite a huge harem of concubines, there was a succession crisis in 1883. One monarch was deposed after only 3 days of nominal power, the next was forced to kill himself by the regents appointed by Tu Duc for giving up more power to the French and the third was assassinated by poison after discovering an illicit relationship between one of the regents and his adopted mother. The situation was becoming chaotic and the people as well as the French were becoming very concerned. The following year, in 1884, the regents put the boy-Emperor Ham Nghi on the throne. The next year, on July 4, the corrupt and powerful regent Ton That Thuyet, who the French had wanted removed, launched a brazen attack on the French garrison in Hue. When they moved to retaliate he took the young Emperor and fled to the mountains where he used the name of the young monarch to call for a rebellion against the French in Vietnam. The French responded by sponsoring the enthronement of the eldest of the three nephews Tu Duc had adopted as his heirs who became Emperor Dong Khanh. |

|

| Emperor Dong Khanh |

|

|

|

|

|

| In the countryside, the rebels who rose up to fight against the French in what became known as the Mandarins Revolt acted with great brutality toward anyone even suspected of having French connections. Naturally, the French missionaries and their Vietnamese converts were a prime target and a new wave of persecutions began. The French troops reacted forcefully as did the Vietnamese forces of the new Emperor Dong Khanh, who put his father-in-law, General Nguyen Than, in command of the troops aiding the French in fighting the rebels. Many Catholics were massacred but God was still with the Vietnamese and once again, in their darkest hour, the Holy Mother came to comfort and protect her children. At a little church in Tra Kieu, the Catholics gathered for shelter as a massive rebel army closed in on them. Interestingly, it was the pagan attackers who testified as to the veracity of this appearance of Our Lady, not the devout Catholics inside who were praying their rosaries and preparing their able-bodied men to go out and defend them. |

|

|

| As the rebel troops were attacking the village they noticed a beautiful lady dressed in white walking on the roof of the parish church. Immediately they ordered their cannon to fire on her but none of the shots came close. They carefully sighted their guns and fired again but still, miraculously, neither the lady nor the church was harmed. Then, in an audacious counterattack, the Vietnamese Catholics rushed in from both sides and defeated the rebel army, which massively outnumbered them, and forced them to retreat. After the details of the story came out, the Catholics gratefully attributed their victory and survival to the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary and Our Lady of Tra Kieu as she came to be called became probably the second most significant Marian shrine and pilgrimage destination in Vietnam. Thankfully, with the help of Our Lady, the French and loyalist Vietnamese emerged successful. The regent Ton That Thuyet fled to China, abandoning the fugitive former boy emperor who was captured by the French and exiled to Algeria. At the Forbidden City in Hue, in 1886 Emperor Dong Khanh officially reestablished freedom of religion and toleration for Catholics and the long period of religious persecution was finally over. |

|

|

| Also during the reign of Dong Khanh the colonial authorities officially established the French Union of Indochina which included all of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Free of legal harassment and persecutions the Church in Vietnam began to flourish and expand, eventually becoming second only to the Philippines as the largest Catholic population in the Far East. The Church also undertook a major education program since, although Vietnamese youth were taught their history and culture and there were classes on the literature of Confucius, there was a near total lack of emphasis or understanding on the natural sciences in Vietnam. There was also an effort to stress friendship between the French and the Vietnamese as well as respect for the colonial system and pride in the worldwide French Empire and the "mission to civilize" which did not always take very well. Revolutionary movements continued to harass but with little effect. The next two Vietnamese emperors, both sponsored by the French were deposed; the first for insanity and his son for attempting to spark a rebellion during World War I. |

|

|

|

|

|

| After these two painful episodes the French turned again to the senior line of Emperor Dong Khanh and enthroned his son as Emperor Khai Dinh, who proved to be friendly enough and devoted to peace with the French. He also gained first hand experience of the power of the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary. In the early 1920's Emperor Khai Dinh became extremely ill and though he was himself a staunch Buddhist he asked one of his officials who was Catholic to pray for him at the shrine of Our Lady of Lavang. Perhaps the Emperor had heard about the promise Mary made there? In any event, the power of God was felt as this Catholic went to the shrine, prayed for the intercession of Mary on behalf of the Emperor and immediately thereafter Khai Dinh completely recovered. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emperor Khai Dinh |

|

|

| One of the most important native Vietnamese officials at this stage was the Catholic mandarin Nguyen Huu Bai. He was a Vietnamese traditionalist, a staunch Catholic and a monarchist who favored a more strict interpretation of the protectorate treaty, which caused many of the French to see him as an enemy. He was also probably the most prominent Catholic Vietnamese of his time. He held a seat on the Privy Council under Emperor Khai Dinh and rose to become interior minister and to some extent the prime minister of Vietnam. He held considerable influence following the death of Khai Dinh when his young son, the Emperor Bao Dai, was living in France awaiting his majority to assume the throne. He attracted other Catholics like himself who were loyal to the monarchy but wanted change in the way the colonial system operated with more authority given to the native government rather than the French. One of the rising stars at court he took under his wing was a young Catholic mandarin named Ngo Dinh Diem who would one day become known all over the world. Some of the other non-Christians at court even accused Nguyen Huu Bai of plotting to seize power and place a Catholic emperor on the Vietnamese throne. That is certainly not true, but he was a force to be reckoned with to be sure. |

|

|

| The Catholic Nguyen Huu Bai was to be the focus of the first major controversy of the reign of Emperor Bao Dai after he returned to his homeland after having grown up in France. In a surprise move known as the Coup of 1933 Emperor Bao Dai abolished the offices of Prime Minister and President of the Privy Council, held by Nguyen Huu Bai and took over their roles himself as well as replacing the old Council with five ministers answerable to him; one of whom was the Catholic patriot Ngo Dinh Diem who was made Minister of the Interior. The French, who were not always friendly with Nguyen Huu Bai, accused him of trying to discredit Bao Dai for being more French than Vietnamese, lazy and interested only in gambling and sports. Whether as strong a monarchist as Nguyen Huu Bai would do this is uncertain, but even if he did, time would prove this assessment of the Emperor to be entirely correct. Many of the old councilors and the dowager queens of the harem also disliked the western clothes Bao Dai preferred to wear and the western habits he had acquired in France. In any event, the matter ended with Nguyen Huu Bai respectfully going into retirement with the new title of Senior Advisor while the conservatives at court grumbled that French education had made Bao Dai a liberal. |

|

|

|

|

| By this time the Church had reached what was, probably, her peak of greatness in Vietnam. The persecutions were long over, missionaries were free to preach, teach and convert and Catholic communities were springing up across the length of Vietnam from north to south. The church honoring Our Lady of Lavang was expanded and embellished and Catholicism had grown to be one of the dominant religions in the country. Even more of a social boost for the Church was to come in 1934 when Emperor Bao Dai married a beautiful young lady and devout Catholic from southern Vietnam named Marie Therese Nguyen Huu Hao Thi Lan. She was the daughter of a wealthy merchant and had been educated in France which impressed the Emperor as much as her lovely appearance. There was a problem with the marriage though which was the religion of the couple. Obtaining a papal dispensation for a Catholic to marry a non-Catholic was not impossible, but it required that the children of such a union be raised in the faith. This presented a problem since the heir to the throne, who would eventually succeed his father, would be expected to perform the pagan rites of the country which a Catholic could not do. An additional papal dispensation was sought for this, but it was too much for the Church to agree to even with French officials warning Rome that Catholic England was lost over the refusal to agree to a marriage as well. In the end, the couple had to accept a civil marriage only, but time would prove this controversy to be rather meaningless in the end, with the Church emerging victorious. |

|

|

|

Empress Nam Phuong |

|

|

|

| Emperor Bao Dai, in an almost unprecedented move, abolished the traditional harem and gave his new Catholic wife the title and name of Empress Nam Phuong or "Southern Perfume". Sadly, just because Bao Dai had abolished the harem it did not mean he had embraced monogamy. While in France he had gained a taste for white girls and enjoyed a long succession of French and Asian mistresses though he did manage to father five children by Empress Nam Phuong. Such infidelity was common for the pagan emperors of Vietnam who often had huge numbers of concubines (Minh Mang is said to have had over 100 and Tu Duc had around 103) but as a Catholic, Empress Nam Phuong expected better, especially after Bao Dai abolished the harem and the system of concubinage, only to still want to enjoy all the benefits without granting any status to the women involved. Her rage was intense at first at the numerous betrayals of her husband, but eventually she devoted herself to her children and her country and over the years the couple grew apart until, though not officially separated, they lived almost entirely apart. Empress Nam Phuong remained though a beloved figure, much more so than her husband, especially by the Catholics of Vietnam who saw in her status a shining symbol of how far they had come in Vietnam with the Nguyen Dynasty since the persecutions of Minh Mang and Tu Duc. |

|

|

|

|

| There were, however, problems brewing which would ultimately effect the Church over the long term and that was the growth and spread of nationalist revolutionary movements. Fortunately, by now enough Vietnamese were Catholics so that the Christian community did not stand out quite as much as being allies of the French. In fact, many Vietnamese Catholics opposed French colonialism while others supported it or at least did not see the French as an enemy. These revolutionary groups were mostly nationalistic and republican, opposing the French and the native Nguyen monarchy. Some were inspired by the Chinese republicans and others took their example from the Communist movement. Originally these movements were not very well led and the French and loyalist Vietnamese had little trouble suppressing them. Yet, French actions also encouraged further resistance by their own actions. When, for example, the French refused to grant further power to the new regime of Emperor Bao Dai, the Catholic minister Ngo Dinh Diem resigned rather than participate in a charade (and the first person he informed of this was his Catholic mentor Nguyen Huu Bai). The Emperor himself decided not to make a fuss and simply occupied his time with his mistresses, hunting and a luxurious lifestyle. |

|

|

| Emperor Bao Dai |

|

|

| All of this changed though with the onset of World War II. After France had been conquered by Nazi Germany, the regime of Marshal Petain set up at Vichy allowed the Japanese to occupy Indochina and use their bases there for their campaigns in Southeast Asia. Because of this, the Japanese left the French regime alone throughout most of the war. By 1945, however, with defeat looming on the horizon, the Japanese became more desperate and attacked the French regime and seized power. Emperor Bao Dai, seeing the wind shift, declared Vietnamese independence from France and joined the Japanese "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" with a new government led by Tran Trong Kim that was Japanese friendly. Throughout the war though, the one group to gain power consistently was the Communists led by an enigmatic figure now calling himself Ho Chi Minh. He gained American support by fighting the Japanese and gained popular support among the Vietnamese peasants by fighting the French and promising a free and independent republic to replace the French colonial empire. |

|

|

| When the collapse of Japanese power came, the Communists seized the opportunity and in August of 1945 declared the independence of what they called the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Emperor Bao Dai, who had himself declared independence only a few months before, saw that the wind had shifted again and abdicated his throne to the Communists, pledging support to the new government and even joining Ho Chi Minh in Hanoi as Supreme Advisor before moving to China. Vietnam was in a chaotic position and it was only in the south, which British troops had occupied and who used the surrendered Japanese still on hand, that the Communists were unable to seize power. Therefore, when the French returned it was southern Vietnam that was to be their base of operations. As an interesting side note, the Catholic Empress of Vietnam moved to France where, as the Nguyen monarchy had been surrendered, she raised her children in the Catholic faith remaining a beloved figure until her tragic death in 1963 from throat cancer. |

|

|

| Within Vietnam, as the French struggled to recover from their own defeat and occupation to restore their position in Vietnam, they turned to a distinctly Catholic figure and that was Admiral Georges Thierry d'Argenlieu. An accomplished naval officer, d'Argenlieu had retired after World War I and joined the Carmelite order taking the name of Louis of the Trinity. However, the Nazi invasion caused him to leave his religious life and return to the military where he joined the Free French Forces of Charles DeGaulle. In 1946 he was appointed the first High Commissioner to Indochina with the goal of reestablishing French power in the region. Like DeGaulle he believed in the glory of France and was committed to maintaining the French Empire. This, along with his Catholicism, meant that he was a determined enemy of the atheistic Communist regime gaining a foothold in the north. He set up a new government in Saigon and appointed influential Vietnamese to important posts. He opposed any concessions to the Communists and preferred to fight rather than to negotiate to maintain the honor of France and protect French interests. To protect the area that had long been the closest to France, the extreme south of Vietnam, Admiral d'Argenlieu proclaimed the Republic of Cochinchina. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ho Chi Minh was violently opposed to any pro-French forces remaining in Vietnam but his still fairly weak position forced him to give way on the subject of Cochinchina for a time. Nonetheless, it did not take long for fighting to break out between the French and the Communists, initiating the First Indochina War. Once fighting had broke out d'Argenlieu argued that any further negotiations with Ho Chi Minh were hopeless and suggested returning Vietnam to the Nguyen monarchy. In France there was also considerable political chaos and when a more leftist government took power Admiral d'Argenlieu was recalled to France, basically for being too committed to victory over the enemies of France than the liberals were comfortable with, many of whom were socialists not far removed ideologically from Ho Chi Minh himself. |

|

|

|

|

|

President Ho Chi Minh |

|

|

| France had no less than fourteen prime ministers during the years of the Indochina War which did nothing to help the French cause. The United States, eager to stop the spread of Communism, ended up providing roughly 80% of the French war effort as well as providing material and a few advisors to the French forces which were hard pressed. The Catholic community also contributed to the war, and though there were some supposed Catholics who joined the Communists in the north, the faithful Catholics knew they could never support a regime based on atheism and hatred of tradition and so determined to resist them. The largest concentrations of Catholic forces were in the Ben Tre province of Cochinchina and Phat Diem in Annam. In Ben Tre, a Franco-Vietnamese officer named Colonel Jean Leroy formed the first Catholic Brigade in 1947 on An Hoa Island. These 60 man brigades were merged to form the UMDC or Mobile Christian Defense Units which operated throughout the province in support of the local units called Bao An or Peace Guardians. When the regular French forces were withdrawn from the area in 1949 Leroy was given command of all UMDC units and responsibility for the whole province. It is a testament to the effectiveness of the Catholic troops that within one year they had the entire province pacified and free of Communist harassment. |

|

|

| However, Colonel Leroy was to face more trouble from his own side than from the Communists. Knowing that the oppressed peasants were the primary base of support for the Communists, Leroy lowered their taxes and ordered the wealthier |

|

|

|

|

|

|

CONTINUE |

|

|

|